Request Demo

Last update 08 May 2025

titin

Last update 08 May 2025

Basic Info

Synonyms cardiomyopathy, dilated 1G (autosomal dominant), CMD1G, CMH9 + [9] |

Introduction Key component in the assembly and functioning of vertebrate striated muscles. By providing connections at the level of individual microfilaments, it contributes to the fine balance of forces between the two halves of the sarcomere. The size and extensibility of the cross-links are the main determinants of sarcomere extensibility properties of muscle. In non-muscle cells, seems to play a role in chromosome condensation and chromosome segregation during mitosis. Might link the lamina network to chromatin or nuclear actin, or both during interphase. |

Related

1

Drugs associated with titinUS11617783

Patent MiningTarget |

Mechanism- |

Originator Org. |

Active Indication |

Inactive Indication- |

Drug Highest PhaseDiscovery |

First Approval Ctry. / Loc.- |

First Approval Date20 Jan 1800 |

100 Clinical Results associated with titin

Login to view more data

100 Translational Medicine associated with titin

Login to view more data

0 Patents (Medical) associated with titin

Login to view more data

3,328

Literatures (Medical) associated with titin31 Dec 2025·Annals of Medicine

Construction of a novel prognostic model based on lncRNAs-related to DNA damage repair for predicting the prognosis of clear cell renal cell carcinoma

Article

Author: Chen, Peng ; Tian, Renli ; Li, Jian

01 Dec 2025·Molecular Genetics and Genomics

Haplotyping-based preimplantation genetic testing for inherited cardiovascular disease: a multidisciplinary approach

Article

Author: Yang, Jingya ; Sun, Yingpu ; Bao, Xiao ; Liu, Han ; Jin, Haixia ; Bu, Zhiqin ; Shi, Hao ; Song, Wenyan ; Zhang, Yuxin ; Niu, Wenbin

01 Jun 2025·Laboratory Investigation

Development of a Technique for Diagnosis and Screening of Superficial Bladder Cancer by Cell-Pellet DNA From Urine Sample

Article

Author: Kang, Chan-Koo ; Paick, Sung Hyun ; Kwak, Hee Jeong ; Seok, Jaekwon ; Kim, Ah Ram ; Lim, Kyung Min ; Choi, Woo Suk ; Cho, Ssang-Goo ; Park, Hyoung Keun ; Kim, Aram ; Kim, Hyeong Gon ; Jeon, Tak-Il ; Lee, Baeckseung ; Kwak, Yeonjoo

8

News (Medical) associated with titin18 Feb 2025

— Day 90 biopsy data reported from first 3 participants dosed in Phase 1/2 INSPIRE DUCHENNE trial — — Average microdystrophin expression of 110% (N=3) and significant improvements in multiple additional muscle health biomarkers observed support the potential of SGT-003 as a next-generation, best-in-class Duchenne muscular dystrophy gene therapy candidate — — Encouraging early signals of potential cardiac benefit observed — —SGT-003 has been well-tolerated in the 6 participants dosed as of February 11, 2025, with no serious adverse events observed — — Participant enrollment continues, with the 7th participant dosed on February 17, 2025; Company expects to dose approximately 20 total participants by Q4 2025 — — In mid-2025, Company plans to request an FDA meeting to discuss potential accelerated approval pathway for SGT-003 — — Company to hold a conference call today at 8:00 AM ET —

CHARLESTOWN, Mass., Feb. 18, 2025 (GLOBE NEWSWIRE) -- Solid Biosciences Inc. (Nasdaq: SLDB), a life sciences company developing precision genetic medicines for neuromuscular and cardiac diseases, today announced positive initial data from the Phase 1/2 INSPIRE DUCHENNE trial evaluating SGT-003, a next-generation gene therapy product candidate intended for the treatment of Duchenne muscular dystrophy (Duchenne). Interim 90-day biopsy data reported in the first three participants showed an average microdystrophin expression of 110%, as measured by western blot, and improvements in multiple biomarkers that are indicators of muscle health and resilience.

“We are extremely pleased to present our initial clinical data from the INSPIRE DUCHENNE trial,” said Bo Cumbo, President and CEO, Solid Biosciences. “When starting this trial, we committed to comprehensively analyzing the effects of SGT-003. To that end, three different measurement methodologies showed what we believe to be potential best-in-class expression of our differentiated microdystrophin transgene. Significant reductions observed in all evaluated clinical biomarkers of muscle damage associated with Duchenne provide preliminary evidence of a beneficial effect in muscle integrity, including potential early signals of a positive cardiac benefit of SGT-003 in these young boys. In mid-2025, we plan to request a meeting with the FDA to discuss the potential for an accelerated approval regulatory pathway for SGT-003.”

SGT-003 was well-tolerated in the first six participants dosed as of the data cutoff date of February 11, 2025. As of the cutoff date, all six participants have reached at least 20 days post SGT-003 treatment. Adverse events (AEs) observed after SGT-003 treatment were typical of those observed in AAV gene therapy, including nausea, vomiting, fever and transient declines in platelets in some participants. No serious adverse events (SAEs) or suspected unexpected serious adverse reactions (SUSARs) were observed, and there was no evidence of thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA), atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS), or hemolysis. Importantly, none of the AEs that were observed required the use of additional immunomodulatory agents such as eculizumab, sirolimus or rituximab.

“The robust microdystrophin expression, improvements in markers of muscle integrity and health, and favorable safety profile observed in this cohort of participants as of the data cutoff date of February 11, 2025, are very promising,” said Craig McDonald, MD, Chair, Department of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation at UC Davis Health and investigator in the INSPIRE DUCHENNE trial. “In the landscape of genetic therapies for Duchenne, individual microdystrophin constructs likely have unique efficacy and safety profiles. I am very encouraged by the initial results reported today and look forward to seeing additional data and longer-term functional data that I believe will further inform our understanding of the role that the nNOS binding domain, which is unique to SGT-003, may play in improving clinical outcomes.”

“While loss of normal dystrophin is the defining molecular hallmark of Duchenne, there is growing understanding within the community that the success of microdystrophin gene therapy extends beyond expression, and will also depend on signals of restoration and preservation of muscle health, which were observed in these early clinical data,” said Gabriel Brooks, MD, Chief Medical Officer at Solid. “We are highly encouraged by the safety and tolerability profile observed, which has been consistent with AAV-based gene therapies. Additionally, though the trial was geared to follow cardiac measures for safety, we were gratified to observe early signs of cardiac benefit, including a decline in hs-troponin I levels in the participant with elevated levels at baseline, and improvements in cardiac function by echocardiography at day 180 in two participants with borderline low ejection fraction.”

INSPIRE DUCHENNE Trial Design The INSPIRE DUCHENNE trial is a Phase 1/2 first in human, open-label, single-dose, multicenter trial designed to evaluate the safety, tolerability and efficacy of SGT-003 in pediatric patients with Duchenne at a dose of 1E14vg/kg. SGT-003 is administered as a one-time intravenous infusion. As of the data cutoff date of February 11, 2025, a total of six participants have been dosed in the INSPIRE DUCHENNE trial. Enrollment in the INSPIRE DUCHENNE trial is ongoing, with at least 10 total participants anticipated to be dosed by early in the second quarter of 2025 and approximately 20 total participants anticipated to be dosed by the fourth quarter of 2025.

INSPIRE DUCHENNE currently has a total of six active clinical sites in the United States and Canada and approved clinical trial applications (CTAs) in the United Kingdom and Italy. Solid expects to activate additional trial sites by the end of 2025.

90-Day Initial Data The 90-day data reported today as of the data cutoff date of February 11, 2025, includes: microdystrophin expression, measures of restoration and activation of key elements of the dystrophin-associated protein complex, key muscle integrity biomarker evaluation, in each case, from the first three participants dosed in the INSPIRE DUCHENNE trial, and interim safety findings from the first six participants dosed in the INSPIRE DUCHENNE trial. The first three participants are two 5-year-old boys and one 7-year-old boy at the time of dosing. The second three participants are a 6-year-old boy and two 7-year-old boys at the time of dosing.

Microdystrophin Expression and Other Measures at Day 90:

Muscle Integrity Biomarker Evaluation at Day 90 (N=3):

Mean reductions observed in markers of muscle injury and stress: Serum creatine kinase (CK) (IU/L): -57% Serum aspartate aminotransferase (AST) (IU/L): -45% Serum alanine transaminase (ALT) (IU/L): -54% Serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) (IU/L): -60% Mean reductions observed in markers of muscle breakdown and dystrophic regeneration: Serum titin (pmol/L): -42% Embryonic myosin heavy chain (eMHC) positive fibers: -59%

Serum creatine kinase (CK) (IU/L): -57% Serum aspartate aminotransferase (AST) (IU/L): -45% Serum alanine transaminase (ALT) (IU/L): -54% Serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) (IU/L): -60%

Serum titin (pmol/L): -42% Embryonic myosin heavy chain (eMHC) positive fibers: -59%

Measure of Potential Cardiac Benefit:

At Day 180, mean cardiac function increased by 8% (N=2) from baseline as measured by left ventricular ejection fraction The third participant had not reached Day 180 follow up as of the data cutoff date of February 11, 2025

The third participant had not reached Day 180 follow up as of the data cutoff date of February 11, 2025

Reduction in serum cardiac hs-troponin I (hs-cTnI) of -36% observed at Day 90 in one participant who entered the trial with elevated hs-cTnI levels Two of the first three participants entered the study with normal baseline cTnI levels Two participants in total (N=6) had elevated troponin at baseline that reduced below initial baseline values post-dose

Two of the first three participants entered the study with normal baseline cTnI levels Two participants in total (N=6) had elevated troponin at baseline that reduced below initial baseline values post-dose

Safety Update for the First Six Participants Dosed:

SGT-003 was well-tolerated No SAEs observed No SUSARs observed No hospitalizations reported No evidence of TMA or aHUS observed All treatment-related AEs resolved with no sequelae None of the AEs required the use of additional immunomodulatory agents such as eculizumab, sirolimus or rituximab No AEs of hepatic transaminitis observed, including no elevated gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) levels One adverse event of special interest (AESI) was observed Mild, transient hs-troponin I elevation observed (CTCAE Grade 1) that resolved without intervention No clinical evidence of myocarditis observed No EKG or echocardiographic changes observed Most common AEs observed: Nausea/vomiting Transient thrombocytopenia One CTCAE Grade 3 episode that resolved within days without intervention No evidence of hemolysis observed Infusion related hypersensitivity reaction One CTCAE Grade 3 episode of prolonged fever that resolved within days without intervention Fever

No SAEs observed No SUSARs observed No hospitalizations reported No evidence of TMA or aHUS observed All treatment-related AEs resolved with no sequelae None of the AEs required the use of additional immunomodulatory agents such as eculizumab, sirolimus or rituximab No AEs of hepatic transaminitis observed, including no elevated gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) levels One adverse event of special interest (AESI) was observed Mild, transient hs-troponin I elevation observed (CTCAE Grade 1) that resolved without intervention No clinical evidence of myocarditis observed No EKG or echocardiographic changes observed Most common AEs observed: Nausea/vomiting Transient thrombocytopenia One CTCAE Grade 3 episode that resolved within days without intervention No evidence of hemolysis observed Infusion related hypersensitivity reaction One CTCAE Grade 3 episode of prolonged fever that resolved within days without intervention Fever

Mild, transient hs-troponin I elevation observed (CTCAE Grade 1) that resolved without intervention No clinical evidence of myocarditis observed No EKG or echocardiographic changes observed

Nausea/vomiting Transient thrombocytopenia One CTCAE Grade 3 episode that resolved within days without intervention No evidence of hemolysis observed Infusion related hypersensitivity reaction One CTCAE Grade 3 episode of prolonged fever that resolved within days without intervention Fever

One CTCAE Grade 3 episode that resolved within days without intervention No evidence of hemolysis observed

One CTCAE Grade 3 episode of prolonged fever that resolved within days without intervention

Conference Call The Company will host a conference call today, February 18, 2025, at 8:00 AM ET to discuss the positive initial data from the Phase 1/2 INSPIRE DUCHENNE trial evaluating SGT-003. A live and archived webcast of the call will be available on Solid’s website at www.solidbio.com under the “Events” tab in the Investor Relations section, or by clicking here.

Participants may also access the live call by dialing 877-407-2991 (toll-free) or 201-389-0925 (international).

About Duchenne Duchenne is a genetic muscle-wasting disease predominantly affecting boys, with symptoms usually appearing between three and five years of age. Duchenne is a progressive, irreversible, and ultimately fatal disease that affects approximately one in every 3,500 to 5,000 live male births and has an estimated prevalence of 5,000 to 15,000 cases in the United States alone.

About SGT-003 SGT-003 is an investigational gene therapy containing a differentiated microdystrophin construct and a proprietary, next-generation capsid, AAV-SLB101, which was rationally designed to target integrin receptors, and has shown enhanced cardiac and skeletal muscle transduction with decreased liver targeting in nonclinical studies. SGT-003’s microdystrophin construct uniquely includes the R16/17 domains, which localize nNOS to the muscle. Nonclinical studies have shown that nNOS can improve blood flow to the muscle thereby reducing muscle breakdown from ischemia and muscle fatigue. Together, these design features suggest that SGT-003 could be a potential best-in-class investigational gene therapy for the treatment of Duchenne.

About INSPIRE DUCHENNE INSPIRE DUCHENNE is a first-in-human, open-label, single-dose, multicenter Phase 1/2 clinical trial to evaluate the safety, tolerability and efficacy of SGT-003 in pediatric participants with a genetically confirmed Duchenne diagnosis with a documented dystrophin gene mutation. INSPIRE DUCHENNE is a multinational trial designed to enroll participants in the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom and Italy.

About Solid Biosciences Solid Biosciences is a precision genetic medicine company focused on advancing a portfolio of gene therapy candidates targeting rare neuromuscular and cardiac diseases, including Duchenne muscular dystrophy (Duchenne), Friedreich’s ataxia (FA), catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT), TNNT2-mediated dilated cardiomyopathy, BAG3-mediated dilated cardiomyopathy, and additional fatal, genetic cardiac diseases. The Company is also focused on developing innovative libraries of genetic regulators and other enabling technologies with promising potential to significantly impact gene therapy delivery cross-industry. Solid is advancing its diverse pipeline and delivery platform in the pursuit of uniting experts in science, technology, disease management, and care. Patient-focused and founded by those directly impacted by Duchenne, Solid’s mission is to improve the daily lives of patients living with devastating rare diseases. For more information, please visit www.solidbio.com.

Forward-Looking Statements This press release contains “forward-looking statements” within the meaning of the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995, including statements regarding future expectations, plans and prospects for the Company; the ability to successfully achieve and execute on the Company’s goals, priorities and achieve key clinical milestones; the anticipated benefits of SGT-003; the Company’s SGT-003 clinical program, including planned enrollment and site activations in the INSPIRE DUCHENNE trial, planned regulatory interactions and the potential accelerated approval pathway; and other statements containing the words “anticipate,” “believe,” “continue,” “could,” “estimate,” “expect,” “intend,” “may,” “plan,” “potential,” “predict,” “project,” “should,” “target,” “would,” “working” and similar expressions. Any forward-looking statements are based on management’s current expectations of future events and are subject to a number of risks and uncertainties that could cause actual results to differ materially and adversely from those set forth in, or implied by, such forward-looking statements. These risks and uncertainties include, but are not limited to, risks associated with the Company’s ability to advance SGT-003, SGT-212, SGT-501, SGT-601, SGT-401 and other preclinical programs and capsid libraries on the timelines expected or at all; obtain and maintain necessary approvals and designations from the FDA and other regulatory authorities; replicate in clinical trials positive results found in preclinical studies and early-stage clinical trials of the Company’s product candidates; replicate preliminary or interim data from early-stage clinicals trials in the final data of such trials; obtain, maintain or protect intellectual property rights related to its product candidates; compete successfully with other companies that are seeking to develop Duchenne, Friedreich’s ataxia and other neuromuscular and cardiac treatments and gene therapies; manage expenses; and raise the substantial additional capital needed, on the timeline necessary, to continue development of SGT-003, SGT-212, SGT-501, SGT-601, SGT-401 and other candidates, achieve its other business objectives and continue as a going concern. For a discussion of other risks and uncertainties, and other important factors, any of which could cause the Company’s actual results to differ from those contained in the forward-looking statements, see the “Risk Factors” section, as well as discussions of potential risks, uncertainties and other important factors, in the Company’s most recent filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission. In addition, the forward-looking statements included in this press release represent the Company’s views as of the date hereof and should not be relied upon as representing the Company’s views as of any date subsequent to the date hereof. The Company anticipates that subsequent events and developments will cause the Company's views to change. However, while the Company may elect to update these forward-looking statements at some point in the future, the Company specifically disclaims any obligation to do so.

Solid Biosciences Investor Contact: Nicole Anderson Director, Investor Relations and Corporate Communications Solid Biosciences Inc. investors@solidbio.com

Media Contact: Glenn Silver FINN Partners glenn.silver@finnpartners.com

This press release was published by a CLEAR® Verified individual.

Source: Solid Biosciences Inc.

Clinical ResultClinical StudyGene Therapy

27 Jun 2024

THURSDAY, June 27, 2024 -- Rare predicted loss-of-function (pLOF) variants and a polygenic risk score (PRS) are associated with increased atrial fibrillation (AF) risk, according to a study published online June 26 in

JAMA Cardiology

.

Oliver B. Vad, M.D., from Copenhagen University Hospital–Rigshospitalet in Denmark, and colleagues examined rare pLOF variants associated with AF and elucidated their role in risk of AF, cardiomyopathy, and heart failure in combination with a PRS in a genetic association and nested case-control study. Data were included for 403,990 individuals from the U.K. Biobank (median age, 58 years).

Over a median follow-up of 13.3 years, 24,447 participants were diagnosed with incident AF. The researchers identified associations for rare pLOF variants in six genes (

TTN

,

RPL3L

,

PKP2

,

CTNNA3

,

KDM5B

, and

C10orf71

) with AF. In an external cohort,

TTN

,

RPL3L

,

PKP2

,

CTNNA3

, and

KDM5B

were replicated. Rare pLOF variants combined with high PRS conferred an odds ratio of 7.08 for AF. PRS carriers also had a considerable 10-year risk of AF (16 and 24 percent in women and men older than 60 years, respectively). There was an association seen for rare pLOF variants with increased risk of cardiomyopathy before and subsequent to AF (hazard ratios, 3.13 and 2.98, respectively).

"These findings may contribute to possible future genetic risk stratification and improved clinical practice," the authors write.

Several authors disclosed ties to the biopharmaceutical and medical device industries.

Abstract/Full Text

Whatever your topic of interest,

subscribe to our newsletters

to get the best of Drugs.com in your inbox.

Clinical Result

07 Jun 2024

Rich longitudinal clinical and genomic data through a network of diverse U.S. health systems.

SAN MATEO, Calif.--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- Helix the leading population genomics company, is launching new clinico-genomic datasets to enable life science companies to drive precision medicine drug discovery and development. Built through Helix’s extensive health system partnerships, these population-scale cohorts consist of full longitudinal clinical and genomic records that span multiple therapeutic areas including Cardiovascular, Immunology & Inflammation, Metabolic conditions and more.

“Life science researchers can utilize Helix’s diverse clinico-genomic cohorts to better understand genetic factors associated with disease progression and clinical outcomes, as well as validating therapeutic candidates of interest,” said Hylton Kalvaria, Chief Commercial Officer of Helix. “Organizations can also rapidly identify targeted patient populations based on specific genetic and phenotypic criteria to optimize discovery and clinical development.”

Helix’s precision cohorts consist of longitudinal clinical data combined with the company’s proprietary Exome+® sequencing data for over 125,000 patients across the US, all of whom have been consented for recontact. With regular data refreshes, partners receive access to structured EHR fields including clinical diagnosis, procedures, lab results, and prescriptions. As an illustrative example, Helix’s new Cardiometabolic cohort consists of over 50k patients with major Cardiovascular Disease diagnoses, patient vitals and demographics, and key lab results including triglycerides, HbA1c and cholesterol. All of these fields are linked to exome sequencing data with deep and uniform coverage of TTN, MYH7, and hundreds of other Cardiovascular genes.

“As the number of precision therapies in development continues to rapidly expand, clinico-genomic data provide incredible opportunities to develop targeted therapeutics with better safety and efficacy pro ” said James Lu, M.D., Ph.D., CEO and co-founder of Helix. “Using real-world data and genomics, precision medicine has the potential to revolutionize drug development and bring us closer to a future of personalized, tailored treatments.”

About Helix

Helix is the leading population genomics company, enabling health systems, life sciences organizations and payers to accelerate the integration of genomic data into patient care and therapeutic development. Learn more at .

Analysis

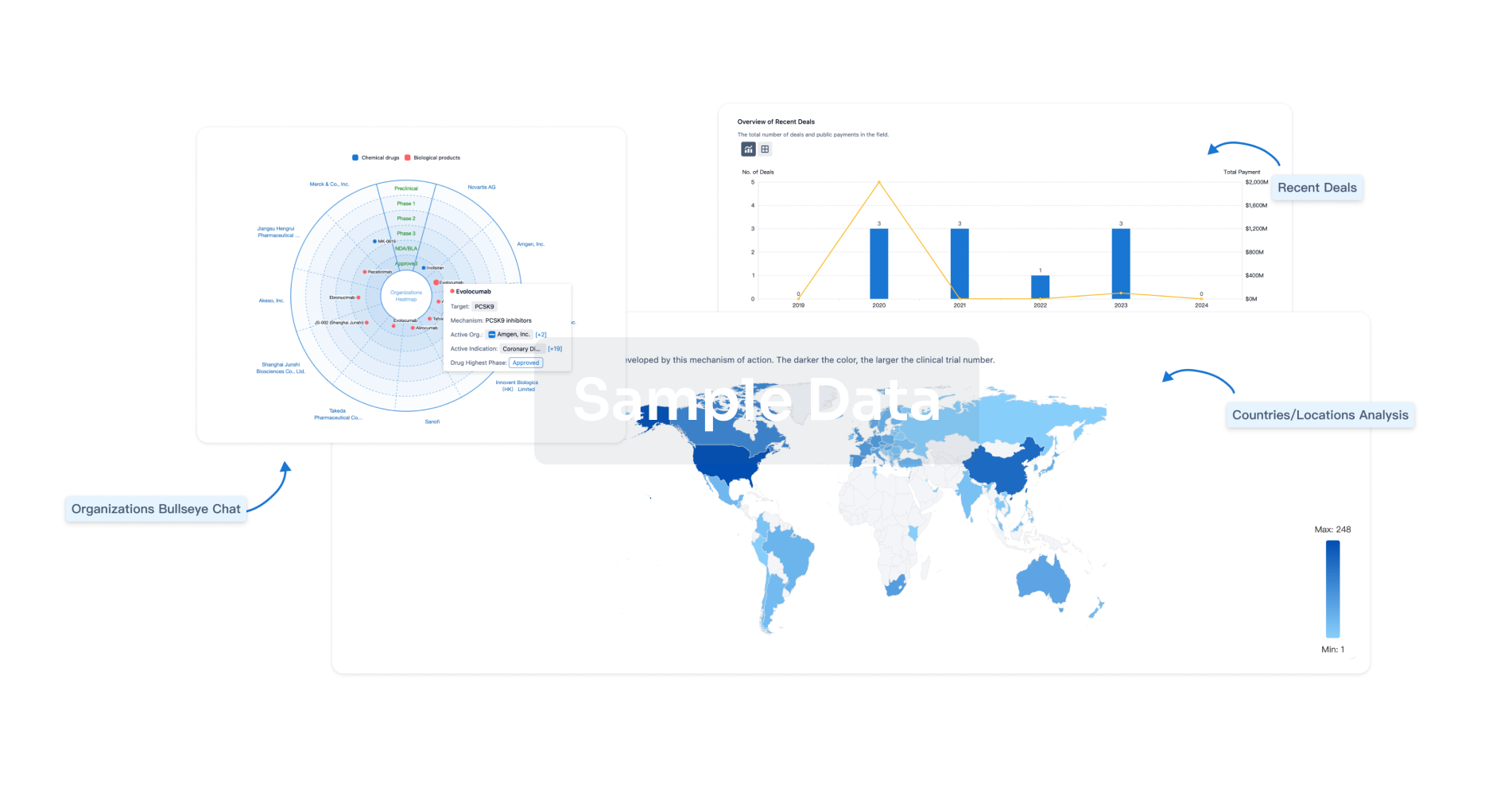

Perform a panoramic analysis of this field.

login

or

AI Agents Built for Biopharma Breakthroughs

Accelerate discovery. Empower decisions. Transform outcomes.

Get started for free today!

Accelerate Strategic R&D decision making with Synapse, PatSnap’s AI-powered Connected Innovation Intelligence Platform Built for Life Sciences Professionals.

Start your data trial now!

Synapse data is also accessible to external entities via APIs or data packages. Empower better decisions with the latest in pharmaceutical intelligence.

Bio

Bio Sequences Search & Analysis

Sign up for free

Chemical

Chemical Structures Search & Analysis

Sign up for free