Request Demo

Last update 08 May 2025

LRH-1

Last update 08 May 2025

Basic Info

Synonyms Alpha-1-fetoprotein transcription factor, B1-binding factor, B1F + [16] |

Introduction Orphan nuclear receptor that binds DNA as a monomer to the 5'-TCAAGGCCA-3' sequence and controls expression of target genes: regulates key biological processes, such as early embryonic development, cholesterol and bile acid synthesis pathways, as well as liver and pancreas morphogenesis (PubMed:16289203, PubMed:18410128, PubMed:21614002, PubMed:32433991, PubMed:38409506, PubMed:9786908). Ligand-binding causes conformational change which causes recruitment of coactivators, promoting target gene activation (PubMed:21614002). The specific ligand is unknown, but specific phospholipids, such as phosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylserine, dilauroyl phosphatidylcholine and diundecanoyl phosphatidylcholine can act as ligand in vitro (PubMed:15707893, PubMed:15723037, PubMed:15897460, PubMed:21614002, PubMed:22504882, PubMed:23737522, PubMed:26416531, PubMed:26553876). Acts as a pioneer transcription factor, which unwraps target DNA from histones and elicits local opening of closed chromatin (PubMed:38409506). Plays a central role during preimplantation stages of embryonic development (By similarity). Plays a minor role in zygotic genome activation (ZGA) by regulating a small set of two-cell stage genes (By similarity). Plays a major role in morula development (2-16 cells embryos) by acting as a master regulator at the 8-cell stage, controlling expression of lineage-specifying transcription factors and genes involved in mitosis, telomere maintenance and DNA repair (By similarity). Zygotic NR5A2 binds to both closed and open chromatin with other transcription factors, often at SINE B1/Alu repeats DNA elements, promoting chromatin accessibility at nearby regulatory regions (By similarity). Also involved in the epiblast stage of development and embryonic stem cell pluripotency, by promoting expression of POU5F1/OCT4 (PubMed:27984042). Regulates other processes later in development, such as formation of connective tissue in lower jaw and middle ear, neural stem cell differentiation, ovarian follicle development and Sertoli cell differentiation (By similarity). Involved in exocrine pancreas development and acinar cell differentiation (By similarity). Acts as an essential transcriptional regulator of lipid metabolism (PubMed:20159957). Key regulator of cholesterol 7-alpha-hydroxylase gene (CYP7A) expression in liver (PubMed:10359768). Also acts as a negative regulator of inflammation in different organs, such as, liver and pancreas (PubMed:20159957). Protects against intestinal inflammation via its ability to regulate glucocorticoid production (By similarity). Plays an anti-inflammatory role during the hepatic acute phase response by acting as a corepressor: inhibits the hepatic acute phase response by preventing dissociation of the N-Cor corepressor complex (PubMed:20159957). Acts as a regulator of immunity by promoting lymphocyte T-cell development, proliferation and effector functions (By similarity). Also involved in resolution of endoplasmic reticulum stress in the liver (By similarity).

In constrast to isoform 1 and isoform 2, does not induce cholesterol 7-alpha-hydroxylase gene (CYP7A) promoter activity.

(Microbial infection) Plays a crucial role for hepatitis B virus gene transcription and DNA replication. Mechanistically, synergistically cooperates with HNF1A to up-regulate the activity of one of the critical cis-elements in the hepatitis B virus genome enhancer II (ENII). |

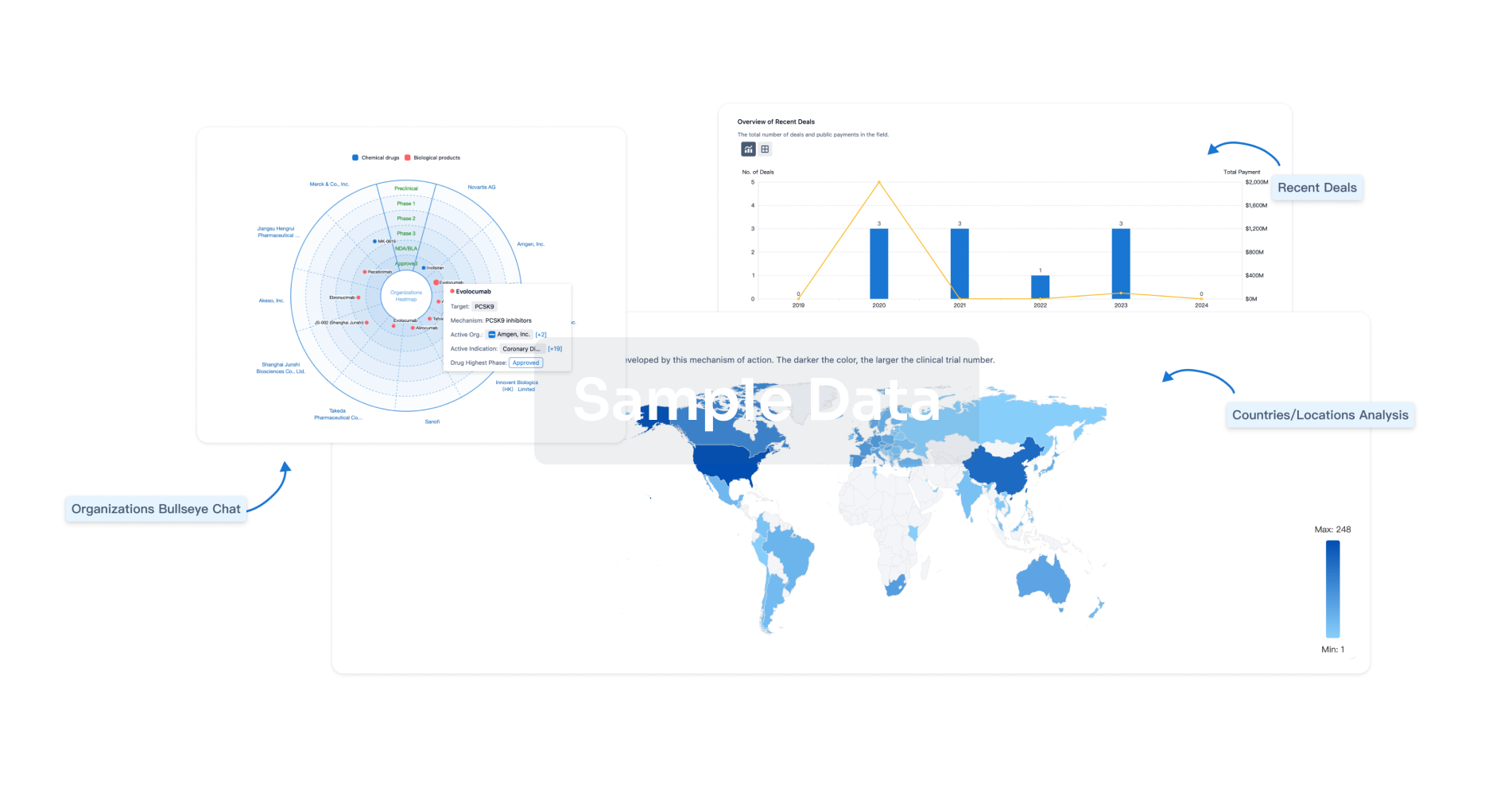

Analysis

Perform a panoramic analysis of this field.

login

or

AI Agents Built for Biopharma Breakthroughs

Accelerate discovery. Empower decisions. Transform outcomes.

Get started for free today!

Accelerate Strategic R&D decision making with Synapse, PatSnap’s AI-powered Connected Innovation Intelligence Platform Built for Life Sciences Professionals.

Start your data trial now!

Synapse data is also accessible to external entities via APIs or data packages. Empower better decisions with the latest in pharmaceutical intelligence.

Bio

Bio Sequences Search & Analysis

Sign up for free

Chemical

Chemical Structures Search & Analysis

Sign up for free