Request Demo

What is drug withdrawal, and when does it occur?

21 March 2025

Understanding Drug Withdrawal

Drug withdrawal is a multifaceted, involuntary physiological and psychological response that arises when a person who has developed dependence on a psychoactive substance – due to chronic or long‐term use – abruptly reduces or stops taking that substance. Essentially, withdrawal is the body’s counter‐regulatory response to the absence of a drug upon which it has become accustomed. Over time, the nervous system adapts to the continual presence of the substance, altering the balance of neurotransmitters, receptor densities, and signaling pathways. When the drug is eliminated or its dosage is sharply decreased, these neuroadaptive changes are unmasked, and the body is unable to immediately re‐establish its normal homeostasis. As a result, a constellation of physical and psychological symptoms emerge, collectively defined as the withdrawal syndrome.

Definition and Mechanisms

Drug withdrawal can be defined as a predictable set of signs and symptoms that occur upon abrupt cessation or significant reduction in the use of a psychoactive substance following a period of sustained, often heavy, use. The underlying mechanisms involve neuroadaptations developed over time in order for the central nervous system to adjust to the drug’s continuous presence. For example, when opioids are repeatedly administered, receptors in the brain, such as the mu‐opioid receptor, become desensitized or downregulated; this homeostatic change is necessary for normal functioning in the presence of the drug but becomes maladaptive when the drug is removed. Consequently, the sudden absence results in abnormal neuronal excitability and an imbalance in cellular signaling pathways – manifesting as withdrawal symptoms. In the context of other substances, such as alcohol, benzodiazepines, or stimulants, the same principles apply. Chronic alcohol use, for instance, induces adaptive changes by increasing excitatory neurotransmission (glutamate) and decreasing inhibitory neurotransmission (gamma‐aminobutyric acid, or GABA) so that, once alcohol is removed, a hyperexcitable state ensues. Thus, regardless of the substance, withdrawal is fundamentally a physiologic “readjustment” period during which the body strives to re‐achieve its pre‐drug equilibrium.

Common Drugs Associated with Withdrawal

Withdrawal is not unique to any one substance but has been observed across a range of drugs. The phenomenon is especially well‐documented in:

- Opioids: Drugs such as heroin, morphine, oxycodone, and fentanyl leave behind a withdrawal syndrome characterized by dysphoria, muscle aches, gastrointestinal upset, and autonomic disturbances. In opioid withdrawal, symptoms can begin as early as four to six hours after the last dose, peaking within one to several days depending on the specific opioid’s half‐life.

- Alcohol: Abrupt reduction in chronic alcohol consumption leads to withdrawal symptoms that might begin as early as six hours after the last drink, with tremors, anxiety, nausea, and in severe cases, seizures and delirium tremens occurring later on. Alcohol withdrawal is particularly dangerous because even a “hangover” syndrome may escalate into life-threatening complications.

- Benzodiazepines: Withdrawal from these sedative-hypnotics can occur following long-term use. Symptoms may include anxiety, insomnia, seizures, and even catatonia in extreme cases. Because benzodiazepines have a dependence potential, withdrawal management often involves gradual tapering to minimize symptom severity.

- Cannabis: Although historically its withdrawal was not well recognized, discontinuation of heavy, prolonged cannabis use can produce symptoms such as irritability, anxiety, sleep disturbances, decreased appetite, and mood changes.

- Psychostimulants: Drugs like cocaine and methamphetamine produce a withdrawal syndrome characterized by dysphoric mood, fatigue, increased appetite, and psychomotor retardation or agitation. For methamphetamine, withdrawal typically features an initial “crash” phase with a rapid onset of exhaustion followed by a more protracted period of depressive and cognitive symptoms.

- Antidepressants and Other CNS Drugs: Although withdrawal from drugs such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) might be milder in some cases, there is increasing evidence that even these medications can result in a discontinuation syndrome if stopped abruptly.

Symptoms and Stages of Withdrawal

Withdrawal is characterized by a wide array of symptoms that affect both the body and the mind. The intensity, type, and duration of these symptoms depend on various factors such as the specific drug, duration and amount of use, individual biology, and the method by which cessation is achieved.

Physical and Psychological Symptoms

Physically, drug withdrawal may manifest as:

- Autonomic overstimulation: Tachycardia, sweating, elevated blood pressure, and hyperventilation are common findings. For example, in alcohol withdrawal, sympathetic hyperactivity can lead to a dangerously high heart rate and blood pressure.

- Gastrointestinal disturbances: Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal cramps can occur, which are frequently observed in opioid and alcohol withdrawal.

- Neurological symptoms: Tremors, muscle cramps, and even seizures (especially in the context of alcohol or benzodiazepine withdrawal) may arise. In opioid withdrawal, muscle and joint aches as well as temperature dysregulation (fever or chills) are common.

- Sensory changes: Visual disturbances, altered taste, and headaches may accompany the withdrawal process.

Psychologically, withdrawal frequently presents with:

- Mood disturbances: Anxiety, depression, irritability, and dysphoria are consistently reported. For instance, withdrawal from opioids and stimulants often results in heightened feelings of anxiety and depression that can persist even after other physical symptoms have subsided.

- Craving: An overwhelming desire or compulsion to take the drug again is a hallmark of withdrawal. This craving is both a symptom of the negative affective state during withdrawal and a key trigger for relapse.

- Cognitive disturbances: Difficulty concentrating, impairments in memory, and in some cases hallucinations (particularly during severe withdrawal such as delirium tremens in alcohol withdrawal) can occur.

- Sleep disturbances: Insomnia, vivid dreams, and disturbances in sleep architecture are common in withdrawal from substances like cannabis, opioids, and stimulants.

The interplay between physical and psychological symptoms creates a profoundly distressing experience that not only challenges the individual physically but also undermines emotional well-being – a dual burden that significantly contributes to the high relapse rates observed in substance use disorders.

Stages and Timeline

Withdrawal symptoms typically follow a temporal sequence that can be segmented into several distinct stages:

- Acute Withdrawal: This phase occurs immediately after cessation of the drug and is characterized by rapidly emerging symptoms. For opioids, spontaneous withdrawal may begin as soon as 4–6 hours after the last dose, with symptoms intensifying over the next 24 to 72 hours. Similarly, in alcohol withdrawal, initial symptoms such as tremors, anxiety, and nausea may appear within 6 hours of cessation, and more severe complications like seizures or delirium tremens typically appear within 1 to 4 days.

- Subacute Withdrawal: Following the acute phase, many individuals experience a subacute stage in which symptoms gradually lessen in intensity but persist at a lower level. In opioid withdrawal, this phase may continue for several days to a week, during which time mood disturbances and craving remain a significant challenge.

- Protracted (Post-Acute) Withdrawal: For some individuals, especially those with a long history of heavy use, a protracted withdrawal state may occur. This stage can last for weeks, months, or even longer and is characterized primarily by psychological symptoms such as dysphoria, anxiety, and lingering cognitive deficits, as well as intermittent physical discomfort. The persistence of these symptoms is thought to contribute to the risk of relapse, as the underlying changes in brain reward and stress systems may remain altered for an extended period.

The timeline for withdrawal is highly variable and closely linked to the pharmacokinetic properties of the drug. For example:

- Short-acting drugs like heroin tend to produce a rapid onset of withdrawal symptoms, while longer-acting opioids such as methadone result in a delayed onset and a prolonged withdrawal course.

- For alcohol, even though some symptoms may subside within days, complications such as delirium tremens may develop several days after cessation, and full recovery from the neuroadaptive changes may take weeks.

- Cannabis withdrawal symptoms typically begin within 1–3 days after cessation, peaking around days 2–6, and gradually diminishing over a period of 7–14 days, though in heavy users some symptoms may persist for over a month.

- Stimulant withdrawal, such as from methamphetamine, has an initial “crash” phase that occurs within 12–24 hours, followed by a more prolonged withdrawal phase that may extend for several weeks with residual cognitive and mood disturbances.

Factors Influencing Withdrawal

The severity, duration, and nature of withdrawal are not uniform across all individuals. Multiple factors influence the withdrawal syndrome, and these can be broadly classified into individual differences and drug-specific factors.

Individual Differences

Individual biological and psychosocial characteristics play a crucial role in modulating the withdrawal process:

- Genetics: There is considerable evidence suggesting that genetic predispositions affect an individual’s likelihood of developing dependence and their subsequent emergence of withdrawal symptoms. Variations in genes that encode for receptors and enzymes involved in drug metabolism can influence the intensity and duration of withdrawal.

- Age and Developmental Stage: Younger individuals and children may experience withdrawal differently compared to adults. For example, pediatric and neonatal populations exposed in utero to opioids or other substances have unique withdrawal profiles and may display distinct neurologic and gastrointestinal symptoms compared to adults.

- Gender: Men and women may report differences in the severity and types of withdrawal symptoms. Some studies have noted that women may experience more intense withdrawal symptoms and can be at greater risk for complications due to hormonal influences and differences in body composition.

- History and Duration of Use: The longer and more heavily a person has used a substance, the more pronounced the neuroadaptive changes, and consequently, the more severe the withdrawal. High cumulative doses and prolonged dependency are consistently associated with a more challenging withdrawal process.

- Psychiatric Comorbidities: The presence of co-occurring mental health disorders such as anxiety, depression, or personality disorders can exacerbate withdrawal symptoms and complicate the individual’s overall recovery process. These comorbidities often result in heightened psychological distress during withdrawal, contributing to the risk of relapse.

Drug-Specific Factors

Alongside individual differences, the pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties of the drug itself determine the pattern of withdrawal:

- Elimination Half-Life: Drugs with a short half-life typically induce a rapid onset of withdrawal symptoms because their levels in the body drop quickly. In contrast, drugs with a long half-life tend to produce a delayed withdrawal profile, which might be prolonged over several days or weeks.

- Potency and Dose: The dosage and potency of the substance when used can predict the severity of withdrawal. Higher doses and more potent formulations lead to more significant physiological adaptations, resulting in more intense and longer-lasting withdrawal symptoms.

- Route of Administration: The manner in which the drug is administered (e.g., intravenous, oral, inhalation) can influence the speed of onset and the intensity of withdrawal. Rapid routes such as intravenous injection can lead to quicker dependence and faster onset of withdrawal upon cessation.

- Drug Interactions and Polysubstance Use: Many individuals use more than one psychoactive substance concurrently, and withdrawal from one drug may be complicated or compounded by the use or withdrawal of another. Polysubstance abuse can result in overlapping withdrawal syndromes, making management more complex.

Management and Treatment of Withdrawal

Managing withdrawal is a critical component not only for alleviating immediate discomfort but also for reducing the risk of relapse and ensuring a successful transition to long-term recovery. The treatment of withdrawal is typically approached through both medical and behavioral strategies.

Medical Interventions

Pharmacotherapy is typically the cornerstone of acute withdrawal management:

- Substitution Therapy: In opioid withdrawal, substitution with a longer-acting opioid agonist such as methadone or a partial agonist like buprenorphine can smooth the transition by preventing the sudden drop in opioid receptor activity. These medications are employed to gradually taper the dose under close medical supervision.

- Symptom-Specific Medications: Withdrawal from alcohol may be managed with benzodiazepines, which help reduce the risk of seizures and ameliorate autonomic hyperactivity. Adjunctive treatments, such as anticonvulsants or medications to correct electrolyte imbalances, may also be utilized. For benzodiazepine withdrawal, a controlled tapering schedule is commonly advised to minimize severe rebound symptoms.

- Alpha-2 Adrenergic Agonists: Medications such as clonidine or lofexidine are useful in reducing some of the autonomic symptoms of opioid and stimulant withdrawal, including tachycardia and hypertension. These agents work by modulating the noradrenergic system, which is often hyperactive during withdrawal.

- Supportive Care: In addition to pharmacotherapy, supportive measures—such as hydration, nutritional support, vitamin supplementation (especially thiamine in alcohol withdrawal), and monitoring in a controlled environment—are essential to safeguard against complications.

The medical management approach is tailored to the individual’s substance, their usage history, and the presence of any co-occurring medical or psychiatric conditions. Rapid or “precipitated” withdrawal, especially in the context of opioid dependence when antagonists like naloxone or naltrexone are administered, requires careful adjustment of dosages and close monitoring.

Behavioral Therapies

Beyond medications, a range of behavioral interventions plays an essential role in both the acute management and long-term recovery from substance use disorders:

- Supportive Counseling and Psychoeducation: Many patients benefit from education about the withdrawal process, what symptoms to expect, and how to manage distress. Counseling helps set realistic expectations and provides coping strategies for dealing with discomfort.

- Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT): CBT techniques target maladaptive thought patterns that contribute to the cycle of dependence and withdrawal. By teaching patients strategies to manage cravings and stress, CBT reduces the emotional burden and risk of relapse during and after withdrawal.

- Mindfulness-Based Interventions (MBIs): Mindfulness practices help individuals increase awareness of bodily sensations and emotional states without reacting impulsively. This can be particularly helpful during withdrawal periods when cravings intensify, allowing individuals to observe and manage these sensations without resorting to drug use.

- Relapse Prevention Strategies: Behavioral therapies that focus on recognizing high-risk situations, triggering cues, and developing effective coping strategies are vital. These interventions are designed to break the cycle of withdrawal-induced relapse by establishing a robust support network and providing ongoing skills training.

Behavioral therapies are most effective when integrated with medical management, offering a holistic approach that addresses both the physiological and psychological components of withdrawal.

Long-term Considerations

While the management of acute withdrawal is critical, long-term strategies must be implemented to ensure sustained recovery and to minimize the risk of relapse. These considerations extend well beyond the initial detoxification phase.

Risks of Relapse

Withdrawal itself represents a significant risk factor for relapse. The intense discomfort—both physical and emotional—that accompanies withdrawal can drive individuals to resume substance use as a means of relief. For example:

- Persistent Symptoms: Even after the acute withdrawal phase has subsided, protracted withdrawal symptoms such as dysphoria, anxiety, and sleep disturbances can persist for weeks or months. These lingering symptoms may serve as potent triggers for relapse, as individuals attempt to self-medicate the residual discomfort.

- Craving and Emotional Distress: Intense craving is inherent to the withdrawal syndrome and is a major contributor to relapse. The memory of drug-induced euphoria juxtaposed with the distress of withdrawal can create a powerful motivational conflict that predisposes patients to return to substance use, particularly in the face of stressful life events.

- Environmental and Social Triggers: Relapse is often precipitated by exposure to environmental cues or social situations associated with prior drug use. This highlights the importance of ongoing psychosocial support even after the withdrawal phase has ended.

Strategies for Sustained Recovery

Ensuring long-term recovery requires comprehensive and sustained interventions that continue well after the completion of the withdrawal process:

- Continued Pharmacotherapy: Maintenance therapies, such as continued use of methadone or buprenorphine for opioid dependence, can help stabilize brain chemistry and reduce craving. Similarly, medications that target co-occurring mental health issues, such as depression or anxiety, may be warranted as part of a long-term treatment plan.

- Integrated Behavioral Therapies: Long-term cognitive-behavioral interventions, mindfulness-based strategies, and relapse prevention planning are critical. These therapies equip individuals with the skills to manage triggers, cope with stress, and maintain abstinence over the long run.

- Support Networks: Participation in support groups, 12-step programs, or structured outpatient services can provide the social reinforcement necessary for sustained recovery. These networks serve as a safety net to help individuals cope with emerging challenges and to mitigate the isolation and emotional distress that often accompany recovery.

- Monitoring and Follow-Up: Regular follow-up with healthcare providers, including both medical and psychiatric assessments, ensures early detection of potential relapse signs and allows for timely intervention. This may include adjusting medication regimens or intensifying behavioral support when needed.

- Holistic and Personalized Approaches: Individualized treatment plans that address unique risk factors—such as gender-specific vulnerabilities, genetic predispositions, and personal coping mechanisms—are crucial for sustained recovery. Tailoring interventions to the individual's specific needs not only improves outcomes but also empowers patients to take an active role in their recovery process.

In summary, successful long-term recovery involves a multifaceted strategy that integrates medication, behavioral therapies, environmental modifications, and the maintenance of strong social connections. A comprehensive treatment plan that evolves with the patient’s needs is critical to minimizing relapse and promoting a lasting recovery.

Detailed Conclusion

Drug withdrawal is a complex syndrome characterized by a spectrum of physical and psychological symptoms that occur upon the abrupt cessation or reduction in use of a psychoactive substance after prolonged exposure. It reflects the body’s adaptive response to long-term substance use, where neurochemical systems such as neurotransmitter signaling and receptor regulation are significantly altered. When the substance is removed, these adaptations result in a state of dysregulation that manifests as withdrawal symptoms. The phenomenon is common across many classes of drugs including opioids, alcohol, benzodiazepines, cannabis, and stimulants, each producing a unique profile based on its pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties.

Withdrawal symptoms can be grouped into physical symptoms (e.g., autonomic hyperactivity, gastrointestinal distress, tremors, and seizures) and psychological symptoms (e.g., anxiety, depression, irritability, and intense cravings). These symptoms typically follow a sequential pattern, beginning with an acute phase, followed by a subacute period, and in some cases evolving into a protracted withdrawal phase. The precise onset and duration of these stages vary by drug; for instance, heroin withdrawal may begin within hours and peak within days, while alcohol withdrawal may progress to complications like delirium tremens a few days after cessation.

Multiple factors influence the severity and duration of withdrawal, including individual differences (genetic predisposition, age, gender, co-occurring mental health conditions, and the patient’s overall history with the drug) as well as drug-specific factors (such as elimination half-life, dosage, and route of administration). These factors determine not only the intensity of the withdrawal syndrome but also the specific constellation of symptoms experienced by the individual.

Effective management and treatment of withdrawal require an integrated approach that combines medical interventions and behavioral therapies. Pharmacotherapy, such as substitution therapies for opioid dependence, benzodiazepines for alcohol withdrawal, and alpha-2 adrenergic agonists for moderating autonomic symptoms, are essential to alleviate the immediate discomfort of withdrawal. Equally important, however, is the incorporation of behavioral interventions—ranging from cognitive-behavioral therapy to mindfulness-based approaches—that help address the psychological distress and maladaptive behaviors associated with withdrawal and prevent relapse.

Long-term considerations in managing drug withdrawal extend beyond the acute and subacute phases. Residual symptoms such as persistent dysphoria, anxiety, and cravings can continue to pose a risk for relapse. Therefore, strategies for sustained recovery must include continued pharmacotherapy, ongoing behavioral support, regular monitoring, and the development of personalized treatment plans that address the unique needs of each individual. Emphasis on relapse prevention is critical, as the struggle with withdrawal and the associated discomfort is a significant factor driving continued substance use.

In conclusion, drug withdrawal is a dynamic and multifactorial process that occurs when the body, having become neuroadapted to the chronic presence of a psychoactive substance, struggles to achieve homeostasis after the substance is removed. It occurs at varying times depending on the drug’s properties, the duration and intensity of use, and individual factors, and it can manifest in a range of physical and psychological symptoms. Managing withdrawal effectively requires a comprehensive approach that not only addresses the immediate symptoms through targeted pharmacotherapy and supportive care but also incorporates long-term strategies designed to sustain recovery and minimize the risk of relapse. Such an integrated, personalized treatment model ultimately provides the best chance for successfully overcoming substance dependence and returning to health.

Drug withdrawal is a multifaceted, involuntary physiological and psychological response that arises when a person who has developed dependence on a psychoactive substance – due to chronic or long‐term use – abruptly reduces or stops taking that substance. Essentially, withdrawal is the body’s counter‐regulatory response to the absence of a drug upon which it has become accustomed. Over time, the nervous system adapts to the continual presence of the substance, altering the balance of neurotransmitters, receptor densities, and signaling pathways. When the drug is eliminated or its dosage is sharply decreased, these neuroadaptive changes are unmasked, and the body is unable to immediately re‐establish its normal homeostasis. As a result, a constellation of physical and psychological symptoms emerge, collectively defined as the withdrawal syndrome.

Definition and Mechanisms

Drug withdrawal can be defined as a predictable set of signs and symptoms that occur upon abrupt cessation or significant reduction in the use of a psychoactive substance following a period of sustained, often heavy, use. The underlying mechanisms involve neuroadaptations developed over time in order for the central nervous system to adjust to the drug’s continuous presence. For example, when opioids are repeatedly administered, receptors in the brain, such as the mu‐opioid receptor, become desensitized or downregulated; this homeostatic change is necessary for normal functioning in the presence of the drug but becomes maladaptive when the drug is removed. Consequently, the sudden absence results in abnormal neuronal excitability and an imbalance in cellular signaling pathways – manifesting as withdrawal symptoms. In the context of other substances, such as alcohol, benzodiazepines, or stimulants, the same principles apply. Chronic alcohol use, for instance, induces adaptive changes by increasing excitatory neurotransmission (glutamate) and decreasing inhibitory neurotransmission (gamma‐aminobutyric acid, or GABA) so that, once alcohol is removed, a hyperexcitable state ensues. Thus, regardless of the substance, withdrawal is fundamentally a physiologic “readjustment” period during which the body strives to re‐achieve its pre‐drug equilibrium.

Common Drugs Associated with Withdrawal

Withdrawal is not unique to any one substance but has been observed across a range of drugs. The phenomenon is especially well‐documented in:

- Opioids: Drugs such as heroin, morphine, oxycodone, and fentanyl leave behind a withdrawal syndrome characterized by dysphoria, muscle aches, gastrointestinal upset, and autonomic disturbances. In opioid withdrawal, symptoms can begin as early as four to six hours after the last dose, peaking within one to several days depending on the specific opioid’s half‐life.

- Alcohol: Abrupt reduction in chronic alcohol consumption leads to withdrawal symptoms that might begin as early as six hours after the last drink, with tremors, anxiety, nausea, and in severe cases, seizures and delirium tremens occurring later on. Alcohol withdrawal is particularly dangerous because even a “hangover” syndrome may escalate into life-threatening complications.

- Benzodiazepines: Withdrawal from these sedative-hypnotics can occur following long-term use. Symptoms may include anxiety, insomnia, seizures, and even catatonia in extreme cases. Because benzodiazepines have a dependence potential, withdrawal management often involves gradual tapering to minimize symptom severity.

- Cannabis: Although historically its withdrawal was not well recognized, discontinuation of heavy, prolonged cannabis use can produce symptoms such as irritability, anxiety, sleep disturbances, decreased appetite, and mood changes.

- Psychostimulants: Drugs like cocaine and methamphetamine produce a withdrawal syndrome characterized by dysphoric mood, fatigue, increased appetite, and psychomotor retardation or agitation. For methamphetamine, withdrawal typically features an initial “crash” phase with a rapid onset of exhaustion followed by a more protracted period of depressive and cognitive symptoms.

- Antidepressants and Other CNS Drugs: Although withdrawal from drugs such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) might be milder in some cases, there is increasing evidence that even these medications can result in a discontinuation syndrome if stopped abruptly.

Symptoms and Stages of Withdrawal

Withdrawal is characterized by a wide array of symptoms that affect both the body and the mind. The intensity, type, and duration of these symptoms depend on various factors such as the specific drug, duration and amount of use, individual biology, and the method by which cessation is achieved.

Physical and Psychological Symptoms

Physically, drug withdrawal may manifest as:

- Autonomic overstimulation: Tachycardia, sweating, elevated blood pressure, and hyperventilation are common findings. For example, in alcohol withdrawal, sympathetic hyperactivity can lead to a dangerously high heart rate and blood pressure.

- Gastrointestinal disturbances: Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal cramps can occur, which are frequently observed in opioid and alcohol withdrawal.

- Neurological symptoms: Tremors, muscle cramps, and even seizures (especially in the context of alcohol or benzodiazepine withdrawal) may arise. In opioid withdrawal, muscle and joint aches as well as temperature dysregulation (fever or chills) are common.

- Sensory changes: Visual disturbances, altered taste, and headaches may accompany the withdrawal process.

Psychologically, withdrawal frequently presents with:

- Mood disturbances: Anxiety, depression, irritability, and dysphoria are consistently reported. For instance, withdrawal from opioids and stimulants often results in heightened feelings of anxiety and depression that can persist even after other physical symptoms have subsided.

- Craving: An overwhelming desire or compulsion to take the drug again is a hallmark of withdrawal. This craving is both a symptom of the negative affective state during withdrawal and a key trigger for relapse.

- Cognitive disturbances: Difficulty concentrating, impairments in memory, and in some cases hallucinations (particularly during severe withdrawal such as delirium tremens in alcohol withdrawal) can occur.

- Sleep disturbances: Insomnia, vivid dreams, and disturbances in sleep architecture are common in withdrawal from substances like cannabis, opioids, and stimulants.

The interplay between physical and psychological symptoms creates a profoundly distressing experience that not only challenges the individual physically but also undermines emotional well-being – a dual burden that significantly contributes to the high relapse rates observed in substance use disorders.

Stages and Timeline

Withdrawal symptoms typically follow a temporal sequence that can be segmented into several distinct stages:

- Acute Withdrawal: This phase occurs immediately after cessation of the drug and is characterized by rapidly emerging symptoms. For opioids, spontaneous withdrawal may begin as soon as 4–6 hours after the last dose, with symptoms intensifying over the next 24 to 72 hours. Similarly, in alcohol withdrawal, initial symptoms such as tremors, anxiety, and nausea may appear within 6 hours of cessation, and more severe complications like seizures or delirium tremens typically appear within 1 to 4 days.

- Subacute Withdrawal: Following the acute phase, many individuals experience a subacute stage in which symptoms gradually lessen in intensity but persist at a lower level. In opioid withdrawal, this phase may continue for several days to a week, during which time mood disturbances and craving remain a significant challenge.

- Protracted (Post-Acute) Withdrawal: For some individuals, especially those with a long history of heavy use, a protracted withdrawal state may occur. This stage can last for weeks, months, or even longer and is characterized primarily by psychological symptoms such as dysphoria, anxiety, and lingering cognitive deficits, as well as intermittent physical discomfort. The persistence of these symptoms is thought to contribute to the risk of relapse, as the underlying changes in brain reward and stress systems may remain altered for an extended period.

The timeline for withdrawal is highly variable and closely linked to the pharmacokinetic properties of the drug. For example:

- Short-acting drugs like heroin tend to produce a rapid onset of withdrawal symptoms, while longer-acting opioids such as methadone result in a delayed onset and a prolonged withdrawal course.

- For alcohol, even though some symptoms may subside within days, complications such as delirium tremens may develop several days after cessation, and full recovery from the neuroadaptive changes may take weeks.

- Cannabis withdrawal symptoms typically begin within 1–3 days after cessation, peaking around days 2–6, and gradually diminishing over a period of 7–14 days, though in heavy users some symptoms may persist for over a month.

- Stimulant withdrawal, such as from methamphetamine, has an initial “crash” phase that occurs within 12–24 hours, followed by a more prolonged withdrawal phase that may extend for several weeks with residual cognitive and mood disturbances.

Factors Influencing Withdrawal

The severity, duration, and nature of withdrawal are not uniform across all individuals. Multiple factors influence the withdrawal syndrome, and these can be broadly classified into individual differences and drug-specific factors.

Individual Differences

Individual biological and psychosocial characteristics play a crucial role in modulating the withdrawal process:

- Genetics: There is considerable evidence suggesting that genetic predispositions affect an individual’s likelihood of developing dependence and their subsequent emergence of withdrawal symptoms. Variations in genes that encode for receptors and enzymes involved in drug metabolism can influence the intensity and duration of withdrawal.

- Age and Developmental Stage: Younger individuals and children may experience withdrawal differently compared to adults. For example, pediatric and neonatal populations exposed in utero to opioids or other substances have unique withdrawal profiles and may display distinct neurologic and gastrointestinal symptoms compared to adults.

- Gender: Men and women may report differences in the severity and types of withdrawal symptoms. Some studies have noted that women may experience more intense withdrawal symptoms and can be at greater risk for complications due to hormonal influences and differences in body composition.

- History and Duration of Use: The longer and more heavily a person has used a substance, the more pronounced the neuroadaptive changes, and consequently, the more severe the withdrawal. High cumulative doses and prolonged dependency are consistently associated with a more challenging withdrawal process.

- Psychiatric Comorbidities: The presence of co-occurring mental health disorders such as anxiety, depression, or personality disorders can exacerbate withdrawal symptoms and complicate the individual’s overall recovery process. These comorbidities often result in heightened psychological distress during withdrawal, contributing to the risk of relapse.

Drug-Specific Factors

Alongside individual differences, the pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties of the drug itself determine the pattern of withdrawal:

- Elimination Half-Life: Drugs with a short half-life typically induce a rapid onset of withdrawal symptoms because their levels in the body drop quickly. In contrast, drugs with a long half-life tend to produce a delayed withdrawal profile, which might be prolonged over several days or weeks.

- Potency and Dose: The dosage and potency of the substance when used can predict the severity of withdrawal. Higher doses and more potent formulations lead to more significant physiological adaptations, resulting in more intense and longer-lasting withdrawal symptoms.

- Route of Administration: The manner in which the drug is administered (e.g., intravenous, oral, inhalation) can influence the speed of onset and the intensity of withdrawal. Rapid routes such as intravenous injection can lead to quicker dependence and faster onset of withdrawal upon cessation.

- Drug Interactions and Polysubstance Use: Many individuals use more than one psychoactive substance concurrently, and withdrawal from one drug may be complicated or compounded by the use or withdrawal of another. Polysubstance abuse can result in overlapping withdrawal syndromes, making management more complex.

Management and Treatment of Withdrawal

Managing withdrawal is a critical component not only for alleviating immediate discomfort but also for reducing the risk of relapse and ensuring a successful transition to long-term recovery. The treatment of withdrawal is typically approached through both medical and behavioral strategies.

Medical Interventions

Pharmacotherapy is typically the cornerstone of acute withdrawal management:

- Substitution Therapy: In opioid withdrawal, substitution with a longer-acting opioid agonist such as methadone or a partial agonist like buprenorphine can smooth the transition by preventing the sudden drop in opioid receptor activity. These medications are employed to gradually taper the dose under close medical supervision.

- Symptom-Specific Medications: Withdrawal from alcohol may be managed with benzodiazepines, which help reduce the risk of seizures and ameliorate autonomic hyperactivity. Adjunctive treatments, such as anticonvulsants or medications to correct electrolyte imbalances, may also be utilized. For benzodiazepine withdrawal, a controlled tapering schedule is commonly advised to minimize severe rebound symptoms.

- Alpha-2 Adrenergic Agonists: Medications such as clonidine or lofexidine are useful in reducing some of the autonomic symptoms of opioid and stimulant withdrawal, including tachycardia and hypertension. These agents work by modulating the noradrenergic system, which is often hyperactive during withdrawal.

- Supportive Care: In addition to pharmacotherapy, supportive measures—such as hydration, nutritional support, vitamin supplementation (especially thiamine in alcohol withdrawal), and monitoring in a controlled environment—are essential to safeguard against complications.

The medical management approach is tailored to the individual’s substance, their usage history, and the presence of any co-occurring medical or psychiatric conditions. Rapid or “precipitated” withdrawal, especially in the context of opioid dependence when antagonists like naloxone or naltrexone are administered, requires careful adjustment of dosages and close monitoring.

Behavioral Therapies

Beyond medications, a range of behavioral interventions plays an essential role in both the acute management and long-term recovery from substance use disorders:

- Supportive Counseling and Psychoeducation: Many patients benefit from education about the withdrawal process, what symptoms to expect, and how to manage distress. Counseling helps set realistic expectations and provides coping strategies for dealing with discomfort.

- Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT): CBT techniques target maladaptive thought patterns that contribute to the cycle of dependence and withdrawal. By teaching patients strategies to manage cravings and stress, CBT reduces the emotional burden and risk of relapse during and after withdrawal.

- Mindfulness-Based Interventions (MBIs): Mindfulness practices help individuals increase awareness of bodily sensations and emotional states without reacting impulsively. This can be particularly helpful during withdrawal periods when cravings intensify, allowing individuals to observe and manage these sensations without resorting to drug use.

- Relapse Prevention Strategies: Behavioral therapies that focus on recognizing high-risk situations, triggering cues, and developing effective coping strategies are vital. These interventions are designed to break the cycle of withdrawal-induced relapse by establishing a robust support network and providing ongoing skills training.

Behavioral therapies are most effective when integrated with medical management, offering a holistic approach that addresses both the physiological and psychological components of withdrawal.

Long-term Considerations

While the management of acute withdrawal is critical, long-term strategies must be implemented to ensure sustained recovery and to minimize the risk of relapse. These considerations extend well beyond the initial detoxification phase.

Risks of Relapse

Withdrawal itself represents a significant risk factor for relapse. The intense discomfort—both physical and emotional—that accompanies withdrawal can drive individuals to resume substance use as a means of relief. For example:

- Persistent Symptoms: Even after the acute withdrawal phase has subsided, protracted withdrawal symptoms such as dysphoria, anxiety, and sleep disturbances can persist for weeks or months. These lingering symptoms may serve as potent triggers for relapse, as individuals attempt to self-medicate the residual discomfort.

- Craving and Emotional Distress: Intense craving is inherent to the withdrawal syndrome and is a major contributor to relapse. The memory of drug-induced euphoria juxtaposed with the distress of withdrawal can create a powerful motivational conflict that predisposes patients to return to substance use, particularly in the face of stressful life events.

- Environmental and Social Triggers: Relapse is often precipitated by exposure to environmental cues or social situations associated with prior drug use. This highlights the importance of ongoing psychosocial support even after the withdrawal phase has ended.

Strategies for Sustained Recovery

Ensuring long-term recovery requires comprehensive and sustained interventions that continue well after the completion of the withdrawal process:

- Continued Pharmacotherapy: Maintenance therapies, such as continued use of methadone or buprenorphine for opioid dependence, can help stabilize brain chemistry and reduce craving. Similarly, medications that target co-occurring mental health issues, such as depression or anxiety, may be warranted as part of a long-term treatment plan.

- Integrated Behavioral Therapies: Long-term cognitive-behavioral interventions, mindfulness-based strategies, and relapse prevention planning are critical. These therapies equip individuals with the skills to manage triggers, cope with stress, and maintain abstinence over the long run.

- Support Networks: Participation in support groups, 12-step programs, or structured outpatient services can provide the social reinforcement necessary for sustained recovery. These networks serve as a safety net to help individuals cope with emerging challenges and to mitigate the isolation and emotional distress that often accompany recovery.

- Monitoring and Follow-Up: Regular follow-up with healthcare providers, including both medical and psychiatric assessments, ensures early detection of potential relapse signs and allows for timely intervention. This may include adjusting medication regimens or intensifying behavioral support when needed.

- Holistic and Personalized Approaches: Individualized treatment plans that address unique risk factors—such as gender-specific vulnerabilities, genetic predispositions, and personal coping mechanisms—are crucial for sustained recovery. Tailoring interventions to the individual's specific needs not only improves outcomes but also empowers patients to take an active role in their recovery process.

In summary, successful long-term recovery involves a multifaceted strategy that integrates medication, behavioral therapies, environmental modifications, and the maintenance of strong social connections. A comprehensive treatment plan that evolves with the patient’s needs is critical to minimizing relapse and promoting a lasting recovery.

Detailed Conclusion

Drug withdrawal is a complex syndrome characterized by a spectrum of physical and psychological symptoms that occur upon the abrupt cessation or reduction in use of a psychoactive substance after prolonged exposure. It reflects the body’s adaptive response to long-term substance use, where neurochemical systems such as neurotransmitter signaling and receptor regulation are significantly altered. When the substance is removed, these adaptations result in a state of dysregulation that manifests as withdrawal symptoms. The phenomenon is common across many classes of drugs including opioids, alcohol, benzodiazepines, cannabis, and stimulants, each producing a unique profile based on its pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties.

Withdrawal symptoms can be grouped into physical symptoms (e.g., autonomic hyperactivity, gastrointestinal distress, tremors, and seizures) and psychological symptoms (e.g., anxiety, depression, irritability, and intense cravings). These symptoms typically follow a sequential pattern, beginning with an acute phase, followed by a subacute period, and in some cases evolving into a protracted withdrawal phase. The precise onset and duration of these stages vary by drug; for instance, heroin withdrawal may begin within hours and peak within days, while alcohol withdrawal may progress to complications like delirium tremens a few days after cessation.

Multiple factors influence the severity and duration of withdrawal, including individual differences (genetic predisposition, age, gender, co-occurring mental health conditions, and the patient’s overall history with the drug) as well as drug-specific factors (such as elimination half-life, dosage, and route of administration). These factors determine not only the intensity of the withdrawal syndrome but also the specific constellation of symptoms experienced by the individual.

Effective management and treatment of withdrawal require an integrated approach that combines medical interventions and behavioral therapies. Pharmacotherapy, such as substitution therapies for opioid dependence, benzodiazepines for alcohol withdrawal, and alpha-2 adrenergic agonists for moderating autonomic symptoms, are essential to alleviate the immediate discomfort of withdrawal. Equally important, however, is the incorporation of behavioral interventions—ranging from cognitive-behavioral therapy to mindfulness-based approaches—that help address the psychological distress and maladaptive behaviors associated with withdrawal and prevent relapse.

Long-term considerations in managing drug withdrawal extend beyond the acute and subacute phases. Residual symptoms such as persistent dysphoria, anxiety, and cravings can continue to pose a risk for relapse. Therefore, strategies for sustained recovery must include continued pharmacotherapy, ongoing behavioral support, regular monitoring, and the development of personalized treatment plans that address the unique needs of each individual. Emphasis on relapse prevention is critical, as the struggle with withdrawal and the associated discomfort is a significant factor driving continued substance use.

In conclusion, drug withdrawal is a dynamic and multifactorial process that occurs when the body, having become neuroadapted to the chronic presence of a psychoactive substance, struggles to achieve homeostasis after the substance is removed. It occurs at varying times depending on the drug’s properties, the duration and intensity of use, and individual factors, and it can manifest in a range of physical and psychological symptoms. Managing withdrawal effectively requires a comprehensive approach that not only addresses the immediate symptoms through targeted pharmacotherapy and supportive care but also incorporates long-term strategies designed to sustain recovery and minimize the risk of relapse. Such an integrated, personalized treatment model ultimately provides the best chance for successfully overcoming substance dependence and returning to health.

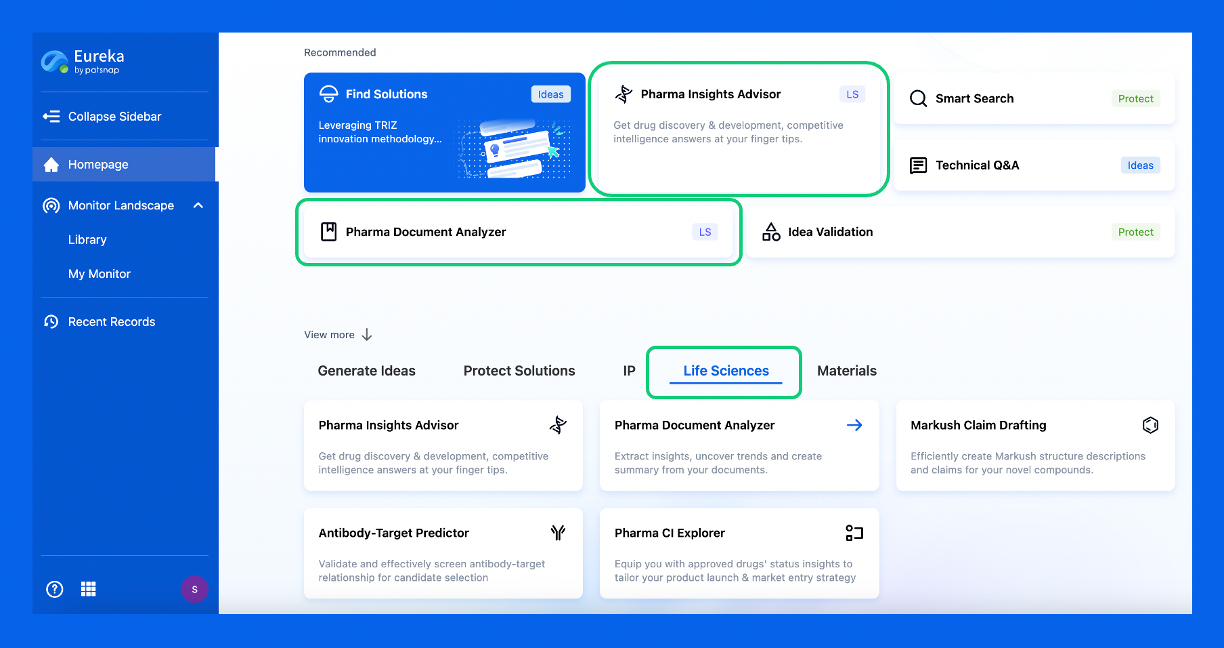

Discover Eureka LS: AI Agents Built for Biopharma Efficiency

Stop wasting time on biopharma busywork. Meet Eureka LS - your AI agent squad for drug discovery.

▶ See how 50+ research teams saved 300+ hours/month

From reducing screening time to simplifying Markush drafting, our AI Agents are ready to deliver immediate value. Explore Eureka LS today and unlock powerful capabilities that help you innovate with confidence.

AI Agents Built for Biopharma Breakthroughs

Accelerate discovery. Empower decisions. Transform outcomes.

Get started for free today!

Accelerate Strategic R&D decision making with Synapse, PatSnap’s AI-powered Connected Innovation Intelligence Platform Built for Life Sciences Professionals.

Start your data trial now!

Synapse data is also accessible to external entities via APIs or data packages. Empower better decisions with the latest in pharmaceutical intelligence.