Request Demo

Last update 29 Jan 2026

Hong Kong Baptist University

Last update 29 Jan 2026

Overview

Tags

Neoplasms

Skin and Musculoskeletal Diseases

Digestive System Disorders

Small molecule drug

Aptamers

Herbal medicine

Disease domain score

A glimpse into the focused therapeutic areas

No Data

Technology Platform

Most used technologies in drug development

No Data

Targets

Most frequently developed targets

No Data

| Top 5 Drug Type | Count |

|---|---|

| Small molecule drug | 8 |

| Herbal medicine | 2 |

| Aptamers | 1 |

| Aptamer drug conjugates | 1 |

| Monoclonal antibody | 1 |

Related

14

Drugs associated with Hong Kong Baptist UniversityTarget- |

Mechanism- |

Originator Org.- |

Active Indication |

Inactive Indication- |

Drug Highest PhasePhase 2 |

First Approval Ctry. / Loc.- |

First Approval Date- |

Target- |

Mechanism- |

Active Org. |

Originator Org. |

Active Indication |

Inactive Indication- |

Drug Highest PhaseClinical |

First Approval Ctry. / Loc.- |

First Approval Date- |

Target |

Mechanism FABP4 inhibitors |

Active Org. |

Originator Org. |

Active Indication |

Inactive Indication- |

Drug Highest PhasePreclinical |

First Approval Ctry. / Loc.- |

First Approval Date- |

114

Clinical Trials associated with Hong Kong Baptist UniversityChiCTR2500113491

Divergent Acute Exercise-Induced Intramyocellular Lipid (IMCL) Responses in Overweight Adults With and Without Prediabetes

Start Date15 Dec 2025 |

Sponsor / Collaborator |

NCT07243223

Epidemiological Profiles, Traditional Chinese Medicine Syndrome, and Biomarkers of Urinary Incontinence in Older Hong Kong Women: A Cross-sectional Study

This is a prospective, cross-sectional study aim to include 1000 patients with urinary incontinence and 100 healthy controls in Hong Kong. The overall objection is to address the gaps in epidemiological profiles, TCM syndrome differentiation, and biomarkers discovery of urinary incontinence among older women. The specific aims including:

1. To assess the epidemiological characteristics of urinary incontinence among older women, as well as patients' knowledge and healthcare-seeking barriers, and to explore factors influencing the disease subtypes, severity, and healthcare-seeking behaviors;

2. To establish diagnostic criteria for traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) syndrome differentiation of urinary incontinence, and analyze the distribution of TCM syndromes;

3. To explore diagnostic biomarkers and severity evaluation biomarkers for three subtypes of urinary incontinence (SUI, UUI, MUI).

1. To assess the epidemiological characteristics of urinary incontinence among older women, as well as patients' knowledge and healthcare-seeking barriers, and to explore factors influencing the disease subtypes, severity, and healthcare-seeking behaviors;

2. To establish diagnostic criteria for traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) syndrome differentiation of urinary incontinence, and analyze the distribution of TCM syndromes;

3. To explore diagnostic biomarkers and severity evaluation biomarkers for three subtypes of urinary incontinence (SUI, UUI, MUI).

Start Date30 Nov 2025 |

Sponsor / Collaborator |

ChiCTR2500112364

Epidemiological Profiles, Traditional Chinese Medicine Syndrome, and Biomarkers of Urinary Incontinence in Older Hong Kong Women: A Cross-sectional Study

Start Date01 Nov 2025 |

Sponsor / Collaborator |

100 Clinical Results associated with Hong Kong Baptist University

Login to view more data

0 Patents (Medical) associated with Hong Kong Baptist University

Login to view more data

7,184

Literatures (Medical) associated with Hong Kong Baptist University01 Apr 2026·NEURAL NETWORKS

Full-spectrum prompt tuning with sparse MoE for open-set recognition

Article

Author: Chen, Jun ; Xie, Yifei ; Geng, Chuanxing ; Hu, Yahao ; Chen, Man ; Pan, Zhisong

Recent advances in open-set recognition leveraging vision-language models (VLMs) predominantly focus on improving textual prompts by exploiting (high-level) visual features from the final layer of the VLM image-encoder. While these approaches demonstrate promising performance, they generally neglect the discriminative yet underutilized (low-level) visual details embedded in shallow layers of the image encoder, which also play a critical role in identifying unknown classes. More critically, despite their significance, integrating such low-level part-based features into textual prompts-typically reflecting high-level conceptual information-remains nontrivial due to inherent disparities in feature representation. To address these issues, we innovatively propose Full-Spectrum Prompt Tuning with Sparse Mixture-of-Experts (FSMoE), which leverages the full-spectrum visual features across different layers to enhance the textual prompts. Specifically, two complementary groups of textual tokens are strategically designed, i.e., high-level textual tokens and low-level textual tokens, where the former interacts with high-level visual features, while the latter for the low-level visual counterparts, thus comprehensively enhancing textual prompts through full-spectrum visual features. Furthermore, to mitigate the redundancy in low-level visual details, a sparse Mixture-of-Experts mechanism is introduced to adaptively select and weight the appropriate features from all low-level visual features through collaborative efforts among multiple experts. Besides, a routing consistency contrastive loss is also employed to further enforce intra-class consistency among experts. Extensive experiments demonstrate the effectiveness of our FSMoE.

01 Mar 2026·JOURNAL OF PHARMACEUTICAL AND BIOMEDICAL ANALYSIS

SuHeXiang Wan in the treatment of stroke: Prediction potentially active metabolites using a combination of in silico analysis and experimental viability assessment

Article

Author: Shen, Lingyu ; Lu, Aiping ; Chen, Yupeng ; Xu, Anqi ; Guan, Daogang ; Li, Wenxing

SuHeXiang Wan (SHXW) is a renowned traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) prescription for treating stroke, but its active components remain largely unidentified. This study aimed to screen potential active compounds of SHXW and reveal their underlying mechanisms in stroke treatment. Ingredients and compounds in SHXW were obtained from TCM databases and subjected to initial screening based on ADMET and physicochemical properties, followed by target gene prediction for each filtered compound. A comprehensive network of filtered compound-target gene-stroke pathogenic gene was constructed and optimized using a multi-objective optimization algorithm. Seventeen potential active compounds were identified, which primarily influenced neuroactive ligand-receptor interactions, arachidonic acid metabolism, and several signaling pathways including PI3K-Akt, calcium, and cAMP. Using an oxygen-glucose deprivation and reoxygenation (OGD/R) model, cirsiliol was identified as the lead compound, significantly enhancing cell viability and morphology, decreasing apoptosis, and reducing oxidative stress and inflammatory responses. Molecular docking and dynamics simulations revealed that cirsiliol stably binds to the NADPH binding pocket of CBR1 protein. Further experiments demonstrated that cirsiliol decreased 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE, a substrate of CBR1) levels. This study provides a methodological framework for screening active compounds in TCM prescriptions. The neuroprotective effects of cirsiliol against ischemic stroke merit further investigation.

01 Mar 2026·GAIT & POSTURE

Artificial intelligence in lower limb joint moment prediction during typically developed gait: A systematic review and multilevel random-effects meta-analysis

Review

Author: Zhou, Zhanyi ; Gao, Zixiang ; Gu, Yaodong ; Li, Fengping ; Baker, Julien S ; Pan, Jianqi ; Chen, Diwei

OBJECTIVE:

Artificial intelligence (AI) methods have been widely applied in gait analysis, yet quantitative comparisons across models and their input-output specifications remain limited. This study aims to systematically review and synthesize the existing literature to evaluate the effectiveness of AI methods in predicting lower limb joint moments during typically developed (TD) gait.

METHODS:

Relevant studies published before July 1, 2025, were retrieved from five databases (PubMed, Scopus, IEEE Xplore, ScienceDirect, and Web of Science) using Boolean logic operations and were screened according to predefined criteria. Risk of bias and applicability were assessed with PROBAST. Meta-analyses were performed in R using a multilevel random-effects model to examine differences in predictive performance across AI model group, signal input type, and output joints.

RESULTS:

Eleven studies involving 371 TD participants met the inclusion criteria. Deep neural networks (DNN) showed the best performance for R2 (0.88, 95 %CI 0.52-1.24), while traditional machine learning (ML) models demonstrated relative superiority for nRMSE (0.11, 95 %CI 0.06-0.29). Among input types, surface EMG (sEMG) achieved the highest R2 (0.96, 95 %CI 0.04-1.89), whereas all inputs except "kinematic and speed and anthropometrics" performed well in the nRMSE analysis. For output joints, the ankle was significantly superior to both the knee (p < 0.001) and the hip (p < 0.001) in terms of R2 and nRMSE.

CONCLUSION:

AI methods can effectively predict lower limb joint moments during TD gait, but differences exist across model group, input type, and output joints. DNN show advantages in fitting complex data, while traditional ML demonstrates greater robustness in small-sample settings. The sEMG, as a process-related input, exhibits high potential, and predictions for the ankle joint are generally superior. Future studies should expand sample size, explore multimodal inputs and advanced modeling strategies, and further validate the applicability of AI methods in pathological gait.

17

News (Medical) associated with Hong Kong Baptist University24 Dec 2025

Researchers have created tiny metal-based particles that push cancer cells over the edge while leaving healthy cells mostly unharmed. The particles work by increasing internal stress in cancer cells until they trigger their own shutdown process. In lab tests, they killed cancer cells far more effectively than healthy ones. The technology is still early-stage, but it opens the door to more precise and gentler cancer treatments.Researchers led by RMIT University have developed extremely small particles called nanodots that can destroy cancer cells while largely leaving healthy cells unharmed. The particles are made from a metal-based compound and represent a possible new direction for cancer treatment research.

The work is still in its early stages and has only been tested in laboratory-grown cells. It has not yet been studied in animals or humans. Even so, the findings suggest a promising strategy that takes advantage of vulnerabilities already present in cancer cells.

A Metal Compound With Unusual Properties

The nanodots are created from molybdenum oxide, a compound derived from molybdenum. This rare metal is commonly used in electronics and industrial alloys.

According to the study's lead researcher Professor Jian Zhen Ou and Dr. Baoyue Zhang from RMIT's School of Engineering, small changes to the chemical structure of the particles caused them to release reactive oxygen molecules. These unstable oxygen forms can damage vital cell components and ultimately trigger cell death.

Lab Tests Show Strong Cancer Selectivity

In laboratory experiments, the nanodots killed cervical cancer cells at three times the rate seen in healthy cells over a 24-hour period. Notably, the particles worked without requiring light activation, which is uncommon for similar technologies.

"Cancer cells already live under higher stress than healthy ones," Zhang said.

"Our particles push that stress a little further -- enough to trigger self-destruction in cancer cells, while healthy cells cope just fine."

International Collaboration Behind the Research

The research involved scientists from multiple institutions. Contributors included Dr. Shwathy Ramesan from The Florey Institute of Neuroscience and Mental Health in Melbourne, as well as researchers from Southeast University, Hong Kong Baptist University, and Xidian University in China. The work was supported by the ARC Centre of Excellence in Optical Microcombs (COMBS).

"The result was particles that generate oxidative stress selectively in cancer cells under lab conditions," she said.

How the Nanodots Trigger Cell Death

To create the effect, the team carefully adjusted the composition of the metal oxide by adding very small amounts of hydrogen and ammonium.

This precise tuning altered how the particles managed electrons, allowing them to produce higher levels of reactive oxygen molecules. These molecules push cancer cells into apoptosis -- the body's natural process for safely removing damaged or malfunctioning cells.

In a separate experiment, the same nanodots broke down a blue dye by 90 percent in just 20 minutes, demonstrating how powerful their chemical reactions can be even in complete darkness.

A Path Toward Gentler Cancer Treatments

Many existing cancer therapies damage healthy tissue along with tumors. Technologies that can selectively increase stress inside cancer cells may lead to treatments that are more targeted and less harmful.

Because the nanodots are made from a widely used metal oxide rather than costly or toxic noble metals such as gold or silver, they may also be more affordable and safer to manufacture.

Next Steps Toward Real-World Use

The COMBS research team at RMIT is continuing to advance the technology. Planned next steps include:

Organizations interested in collaborating with RMIT researchers can contact: [email protected]

14 Aug 2025

HONG KONG, Aug. 14, 2025 /PRNewswire/ -- Testing technologies play a pivotal role in disease diagnosis. Currently, flow cytometers are widely used in the field of biomedicine and are considered the gold standard for diagnosing blood diseases such as leukaemia. However, high-end flow cytometers are extremely expensive, with prices reaching several million Hong Kong dollars. A research team from Hong Kong Baptist University (HKBU) has successfully developed the "Sequential Measurement Based Multi-Parameter Microfluidic Flow Cytomolecular Analyser" (referred to as the "Microfluidic Flow Cytomolecular Analyser"), which leverages innovative technology to significantly improve testing efficiency. It also reduces costs to only one-tenth to one-fifth of similar products in the market so as to benefit more patients.

Continue Reading

Professor Lei Bo, Visiting Professor of the Department of Chemistry at HKBU and Professor in the Department of Life Sciences of the Faculty of Science and Technology at Beijing Normal-Hong Kong Baptist University (1st left) and his team, have developed a Microfluidic Flow Cytomolecular Analyser that can detect cellular characteristics with higher efficiency and lower costs.

The project was recently awarded funding under the "Research, Academic and Industry Sectors One-plus Scheme" (RAISe+ Scheme) launched by the Innovation and Technology Commission of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government to support the commercialisation of its research outcomes.

Flow cytometers, based primarily on laser technology, are molecular testing equipment used to detect cellular characteristics. As cell samples pass through the equipment's channels, they sequentially move through a laser-illuminated area. Fluorescent markers attached to the samples will then emit fluorescence signals, which are detected and recorded by signal receivers. This allows the analysis of both the surface and interior of the cells, including various parameters related to cell morphology, DNA, RNA, and proteins.

Conventional flow cytometers have only one single channel. Detecting six or more parameters simultaneously requires multiple sets of lasers to capture all the fluorescent colour signals from the cells for analysis. The Microfluidic Flow Cytomolecular Analyser developed by the HKBU team uses microfluidic chip technology to greatly enhance detection capabilities without the need to add extra laser sets.

Flow cytometers can detect physical properties of cells, protein expression (including immunophenotyping), total nucleic acid content, functional status and nanoparticles. Among these, immunological assays (antibody-labelled proteins) and nucleic acid quantification (DNA/RNA dyes) are the two most widely used molecular testing methods in clinical and research applications. The Microfluidic Flow Cytomolecular Analyser developed by HKBU integrates the functions of detecting particles and molecules such as cells, proteins and nucleic acids. To ensure testing efficiency, it utilises artificial intelligence to establish data analysis models, enabling the instant processing of tens of thousands of cell data.

Professor Lei Bo, Visiting Professor of the Department of Chemistry at HKBU and Professor of the Department of Life Sciences of the Faculty of Science and Technology at Beijing Normal-Hong Kong Baptist University (BNBU) who leads the research team said: "The Microfluidic Flow Cytomolecular Analyser developed by our team brings together transdisciplinary experts in optical path design, microfluidic chips, software algorithms, and bioinformatics. We utilise research resources from HKBU's Faculty of Science in chemistry, biology, mathematics, and computing, and garnered support by the algorithm developed by the Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Interdisciplinary Research and Application for Data Science at BNBU. By deeply integrating microfluidic chip technology with flow cytometry, we have increased the number of detectable parameters in flow cytometers. Our innovative single-laser, multi-parameter testing technology allows the equipment to detect dozens, or even more than 100, parameters using just one laser set."

Professor Lei said that the seamless collaboration of various departments at HKBU, along with the research team's solid experience of over a decade in developing testing reagents and equipment, complemented by technical support from transdisciplinary experts, insights into industry needs, and effective investor matching provided by the Institute for Innovation, Translation and Policy Research at HKBU, coupled with funding from the RAISe+ Scheme, positions the Microfluidic Flow Cytomolecular Analyser for success in its gradual market application and commercialisation. This leverages its three core advantages of portability, user-friendly operation and cost-effectiveness, thereby accelerating the extensive adoption of precision medical resources and opening up broader prospects for application.

Currently, several research teams at HKBU are engaging in the development and application of diagnostic and bio-testing technologies with remarkable results. Among these is the "Automated Multiplex Diagnostics System" developed by Professor Terence Lau, Interim Chief Innovation Officer at HKBU, which can accurately, rapidly and cost-effectively detect up to 45 respiratory pathogens simultaneously; Professor Ren Kangning, Professor of the Department of Chemistry at HKBU, has developed a "barcode-like cell-based sensor" that enables rapid and low-cost screening for drug-resistant bacteria; and Professor Zhu Furuong, Professor of the Department of Physics at HKBU, has created a multi-mode photodetector that detects both near-infrared and visible light spectra, making it applicable not only to fruit quality and traceability but also to the inspection of the qualities of Chinese herbal medicine. These research achievements will be developed further and applied in fields such as disease diagnosis, environmental monitoring, and food safety.

SOURCE Hong Kong Baptist University

WANT YOUR COMPANY'S NEWS FEATURED ON PRNEWSWIRE.COM?

440k+

Newsrooms &

Influencers

9k+

Digital Media

Outlets

270k+

Journalists

Opted In

GET STARTED

04 Aug 2025

HONG KONG, Aug. 4, 2025 /PRNewswire/ -- A collaborative research team led by Hong Kong Baptist University (HKBU) has developed a multifunctional nanorobot equipped with silver and gold nanorods to facilitate high-performance pollutant degradation and bacteria elimination, with its mobility navigated by the application of magnetic fields. The invention holds potential for broad applications in antibacterial treatments, sewage management, and biomedicine.

Continue Reading

A collaborative research team led by Professor Ken Leung Cham-fai, Associate Professor of the Department of Chemistry at HKBU, has developed a multifunctional nanorobot to facilitate high-performance pollutant degradation and bacteria elimination.

Chemical pollution, pathogenic bacteria, and biofilms (a community of microorganisms embedded in a slimy matrix) pose significant threats to public health. In response, scientists have developed various nanoplatforms with catalytical and antibacterial properties. However, creating a remotely controllable nanorobot with precise targeting and propulsion capabilities, which aims to enhance efficacy and flexibility in treatment strategies, remains a challenge.

Professor Ken Leung Cham-fai, Associate Professor of the Department of Chemistry at HKBU, in collaboration with scientists from the University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei University of Technology, and the Dongcheng branch of the First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University, have designed and fabricated a nanorobot, which demonstrates capabilities in breaking down organic pollutants, exhibits antibacterial properties, and removes biofilms. The research findings have been published in the academic journal Advanced Healthcare Materials.

The multifunctional nanorobot has a hollow spherical structure with the following components and features:

The core composes of iron oxide, a magnetic material that enables control of the nanorobot's movement with the application of magnetic fields, so that the nanorobot can navigate along predetermined paths;

The middle layer consists of silver and gold bi-metallic nanorods, which act as catalyst for chemical reactions that facilitate the degradation of organic pollutants, and inhibit the growth or disrupt the function of bacterial cells;

The outer layer is made of polydopamine, a biocompatible material that protects and stabilises the inner components; and

A large cavity and mesoporous structure that can be used as drug carriers.

To test the efficacy of the nanorobot in pollutant degradation, the research team created simulated miniature wastewater pools. Driven by magnetic fields, the nanorobots accurately moved to two of the chambers and stayed there for one minute. Subsequent tests showed that the levels of both 4-nitrophenol, an organic pollutant from industrial and agricultural activities, and methylene blue, an organic dye typically found in industrial wastewater, were reduced significantly.

The research team also discovered that the nanorobot demonstrates antibacterial capability. The team used the nanorobot loaded with zinc phthalocyanine to investigate the antibacterial effects of silver and gold on Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus under various conditions, including controlling the nanorobots' movement with magnetic fields, and applying light sources including near-infrared laser and xenon lamp irradiation. When magnetic fields, near-infrared laser and xenon lamp irradiation were applied together, the nanorobot loaded with zinc phthalocyanine achieved up to 99.99% inhibition of bacterial proliferation.

The magnetic propulsion capability of the nanorobot loaded with zinc phthalocyanine also enables it to effectively remove bacterial biofilms. When the nanorobots were introduced to biofilms grown in experiment plates, and U-shaped tubes with magnetic fields and light source were applied, they effectively disrupted and removed biofilms. When magnetic fields, near-infrared laser and xenon lamp irradiation were applied together, the most significant biofilm removal and lowest bacterial survival rates were recorded. The study highlights the potential of the nanorobot in addressing biofilm-associated infections and blockages in confined spaces like catheters.

Professor Ken Leung Cham-fai said: "Our research results show that the multifunctional nanorobot developed by our research team exhibits precise catalytic capabilities, high antibacterial activity, and effective biofilm removal properties. Its mobility navigated by magnetic fields enables pollutant degradation and antibacterial activities to be conducted in a controlled, precise and effective manner. This multifunctional nanorobot possesses significant potential for applications in sewage treatment, biomedicine, and other fields."

SOURCE Hong Kong Baptist University

WANT YOUR COMPANY'S NEWS FEATURED ON PRNEWSWIRE.COM?

440k+

Newsrooms &

Influencers

9k+

Digital Media

Outlets

270k+

Journalists

Opted In

GET STARTED

100 Deals associated with Hong Kong Baptist University

Login to view more data

100 Translational Medicine associated with Hong Kong Baptist University

Login to view more data

Corporation Tree

Boost your research with our corporation tree data.

login

or

Pipeline

Pipeline Snapshot as of 26 Feb 2026

The statistics for drugs in the Pipeline is the current organization and its subsidiaries are counted as organizations,Early Phase 1 is incorporated into Phase 1, Phase 1/2 is incorporated into phase 2, and phase 2/3 is incorporated into phase 3

Discovery

3

9

Preclinical

Phase 2

1

5

Other

Login to view more data

Current Projects

| Drug(Targets) | Indications | Global Highest Phase |

|---|---|---|

Renzhu Changle Granules | Irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea More | Phase 2 |

S-2196 | Urinary Incontinence, Stress More | Clinical |

ApmCRP3 ( CRP ) | Rheumatoid Arthritis More | Preclinical |

RO-282653 ( MMP14 ) | Obesity More | Preclinical |

Licochalcone A ( P-gp x PTGR1 ) | Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma More | Preclinical |

Login to view more data

Deal

Boost your decision using our deal data.

login

or

Translational Medicine

Boost your research with our translational medicine data.

login

or

Profit

Explore the financial positions of over 360K organizations with Synapse.

login

or

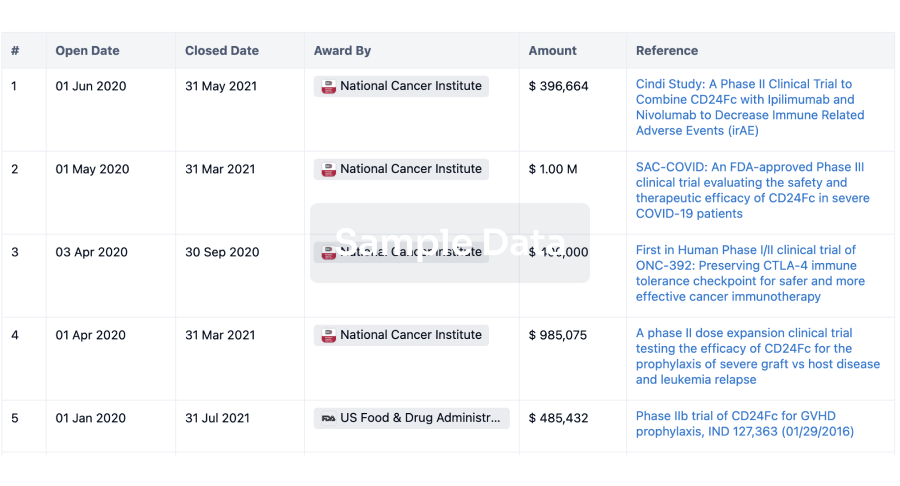

Grant & Funding(NIH)

Access more than 2 million grant and funding information to elevate your research journey.

login

or

Investment

Gain insights on the latest company investments from start-ups to established corporations.

login

or

Financing

Unearth financing trends to validate and advance investment opportunities.

login

or

AI Agents Built for Biopharma Breakthroughs

Accelerate discovery. Empower decisions. Transform outcomes.

Get started for free today!

Accelerate Strategic R&D decision making with Synapse, PatSnap’s AI-powered Connected Innovation Intelligence Platform Built for Life Sciences Professionals.

Start your data trial now!

Synapse data is also accessible to external entities via APIs or data packages. Empower better decisions with the latest in pharmaceutical intelligence.

Bio

Bio Sequences Search & Analysis

Sign up for free

Chemical

Chemical Structures Search & Analysis

Sign up for free