Request Demo

Last update 25 Jan 2026

East China Normal University

Last update 25 Jan 2026

Overview

Tags

Neoplasms

Skin and Musculoskeletal Diseases

Other Diseases

Small molecule drug

Protein drug conjugate

Proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTAC)

Disease domain score

A glimpse into the focused therapeutic areas

No Data

Technology Platform

Most used technologies in drug development

No Data

Targets

Most frequently developed targets

No Data

| Top 5 Drug Type | Count |

|---|---|

| Small molecule drug | 52 |

| Protein drug conjugate | 5 |

| Proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTAC) | 5 |

| Gene editing | 5 |

| HEMTACs | 1 |

Related

75

Drugs associated with East China Normal UniversityTarget |

Mechanism α1A-AR antagonists |

Active Org. |

Originator Org. |

Active Indication |

Inactive Indication |

Drug Highest PhaseApproved |

First Approval Ctry. / Loc. Japan |

First Approval Date02 Jul 1993 |

Mechanism DNA polymerase III inhibitors [+2] |

Originator Org. |

Inactive Indication |

Drug Highest PhaseApproved |

First Approval Ctry. / Loc. United States |

First Approval Date18 Apr 1991 |

Target |

Mechanism VMAT1 antagonists [+1] |

Active Org. |

Originator Org. |

Active Indication |

Inactive Indication- |

Drug Highest PhaseApproved |

First Approval Ctry. / Loc. United States |

First Approval Date12 Aug 1955 |

11

Clinical Trials associated with East China Normal UniversityChiCTR2600117168

The Digital Assessment and Intervention Research of Depression

Start Date10 Jan 2026 |

Sponsor / Collaborator |

ChiCTR2600116574

The Influence of Archery on University Students' Attention Network: An fNIRS-Based Study

Start Date01 Oct 2025 |

Sponsor / Collaborator |

ChiCTR2500103874

Exploring the Effects and Mechanisms of the healthy physical education curriculum model of China on Students' Physical and Mental Health Based on Metabolomics

Start Date06 Sep 2024 |

Sponsor / Collaborator |

100 Clinical Results associated with East China Normal University

Login to view more data

0 Patents (Medical) associated with East China Normal University

Login to view more data

18,505

Literatures (Medical) associated with East China Normal University01 Dec 2026·Nano-Micro Letters

Ultrahigh Dielectric Permittivity of a Micron-Sized Hf0.5Zr0.5O2 Thin-Film Capacitor After Missing of a Mixed Tetragonal Phase

Article

Author: Jiang, An Quan ; Cheng, Yan ; Wang, Wei Wei ; Wang, Xing Ya ; Li, Bing ; Di Zhang, Wen

Abstract:

Innovative use of HfO2-based high-dielectric-permittivity materials could enable their integration into few-nanometre-scale devices for storing substantial quantities of electrical charges, which have received widespread applications in high-storage-density dynamic random access memory and energy-efficient complementary metal–oxide–semiconductor devices. During bipolar high electric-field cycling in numbers close to dielectric breakdown, the dielectric permittivity suddenly increases by 30 times after oxygen-vacancy ordering and ferroelectric-to-nonferroelectric phase transition of near-edge plasma-treated Hf0.5Zr0.5O2 thin-film capacitors. Here we report a much higher dielectric permittivity of 1466 during downscaling of the capacitor into the diameter of 3.85 μm when the ferroelectricity suddenly disappears without high-field cycling. The stored charge density is as high as 183 μC cm−2 at an operating voltage/time of 1.2 V/50 ns at cycle numbers of more than 1012 without inducing dielectric breakdown. The study of synchrotron X-ray micro-diffraction patterns show missing of a mixed tetragonal phase. The image of electron energy loss spectroscopy shows the preferred oxygen-vacancy accumulation at the regions near top/bottom electrodes as well as grain boundaries. The ultrahigh dielectric-permittivity material enables high-density integration of extremely scaled logic and memory devices in the future.

01 Mar 2026·COLLOIDS AND SURFACES B-BIOINTERFACES

A hydroxylated collagen-like construct with an integrin-binding motif produced in a probiotic chassis: Synthesis, structural stability, and in-vitro bioactivity

Article

Author: Zhang, Zheng ; Wang, Cong ; Jin, Mingfei ; Zhang, Jing ; Zheng, Lihui ; Su, Wei ; Wu, Jiajing ; Huang, Jing ; Huang, Yuchen ; Luo, Shijing ; Zhao, Wenjing ; Liu, Tanglin

Recombinant production of collagen in Escherichia coli is pivotal for advancing biomedical applications, yet it is frequently hampered by critical challenges, notably endotoxin contamination and insufficient prolyl hydroxylation. To address these limitations, we engineered the probiotic bacterium E. coli Nissle 1917 (EcN) as a chassis for producing a hydroxylated human type III collagen-like protein named R8. Through the co-expression of R8 with Bacillus anthracis prolyl 4-hydroxylase (BaP4H) in EcN, we achieved a yield of 0.26 mg/mL for the hydroxylated collagen. A hydroxylation rate of 60 % was achieved, with LC-MS/MS mapping confirming modification at 33 out of 65 proline residues. Hydroxylated R8 exhibits enhanced thermal stability, maintaining the structural integrity of its triple helix and assembling into a porous fibrous network. Crucially, R8 from EcN showed reduced immunogenicity in macrophage activation assays, in stark contrast to material from conventional E. coli BL21(DE3). Moreover, hydroxylated R8 exhibits excellent biocompatibility, significantly promoting fibroblast proliferation and migration, and underscoring the critical role of this modification. This study establishes a strategy for producing bioactive collagen, whilst highlighting the critical importance of hydroxylation for collagen stability and function.

01 Feb 2026·ACTA PSYCHOLOGICA

Mental integration and emotional resonance: The relationship between self-other overlap and intimate relationship satisfaction

Article

Author: Zhou, Wenjie ; Wang, Xiu ; Zhang, XinYi ; Hou, Juan

Self-other overlap (SOO), as a core cognitive representation in intimate relationships, significantly influences relationship satisfaction. Grounded in Self-Expansion Theory and the Interpersonal Process Model, this research systematically examines the behavioral and neural pathways through which SOO affects intimate relationship satisfaction via three studies. Study 1 (67 couples) investigated the relationship between SOO, emotional synchrony, and intimate relationship satisfaction through an emotional synchrony experiment. Studies 2 (51 couples) and 3 (36 couples) employed EEG hyperscanning technology to measure prefrontal interpersonal neural synchronization (INS) during independent and interactive emotional synchrony tasks, respectively. These studies further explored the mediating role of INS between SOO and relationship satisfaction. Results revealed that: At the behavioral level, SOO significantly and positively predicted intimate relationship satisfaction, with emotional synchrony acting as a partial mediator. At the neural level, prefrontal INS was significantly negatively correlated with intimate relationship satisfaction. INS partially mediated the relationship between SOO and relationship satisfaction. These findings suggest that partners with high SOO rely on mature, coordinated interaction patterns, thereby reducing the need for real-time neural synchronization and optimizing neural resource allocation. In contrast, partners with low SOO compensate for weaker emotional bonds by enhancing INS; however, this high-energy neural coupling is associated with lower relationship satisfaction. This research provides novel perspectives and empirical evidence for understanding the intrinsic mechanisms of intimate relationships.

10

News (Medical) associated with East China Normal University10 Sep 2025

YolTech Therapeutics, a prolific Chinese biotech that’s already begun testing four CRISPR gene editing therapies in small clinical studies, raised a $44.5 million Series B to test several more genetic medicines in humans and potentially begin its first Phase 3 trial later this year, it told

Endpoints News

in an exclusive interview.

The new round was led by the AstraZeneca-CICC Healthcare Investment Fund, a

$1 billion equity fund

established by the British pharma company and the China International Capital Corporation in 2019.

YolTech’s funding comes amidst soaring attention to Chinese biotech companies, and as

many US gene editing companies

have

cut staff

and

trimmed

once-sweeping pipelines. And while some US gene editing startups are just beginning — or still struggling — to test their first therapies in people, YolTech has wasted no time putting one experimental CRISPR therapy after another into clinical tests.

“If we wanted to survive, we had to move things quickly into the clinic,” YolTech co-founder and CEO Yuxuan Wu told Endpoints. “We showed the investors that gene editing can finally be translated to the clinical stage.”

YolTech’s Chief Technology Officer and co-founder Zi Jun Emma Wang said the new funding — which brings its total raised to $83 million — should support the 90-person company for the two or three years it will take to get its lead program through a Phase 3 trial.

That therapy, YOLT-201, uses CRISPR to edit a gene responsible for an inherited condition called transthyretin amyloidosis, or ATTR. The US biotechs Intellia Therapeutics and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals began their own

Phase 3 trial for the disease

last year. The US study could wrap up in the second half of 2027.

Wang told Endpoints that “it’s possible” YolTech will beat Intellia to pivotal data disclosure and approval, but downplayed that as a goal.

“We’re not trying to compete with Intellia,” she said. “We are focused on generating good safety and efficacy data in the clinic to provide patients, Chinese patients, access to a drug that could be still years away without us.”

Wu learned the ropes of CRISPR

as a postdoc at Boston Children’s Hospital before returning to China to start his own lab at East China Normal University in Shanghai in 2018. He also co-founded a startup, BRL Medicine, to develop a CRISPR therapy for beta-thalassemia.

BRL’s therapy required removing a patient’s cells and editing them in the lab. But Wu became convinced that such

ex vivo

editing would be too expensive for most Chinese patients. And in 2021, he was inspired by

data

from Intellia showing that a simple infusion could edit genes directly inside people’s bodies. A month later, he founded YolTech and teamed up with Wang, who had worked on mRNA delivery at Boston gene editing companies Tessera Therapeutics and Beam Therapeutics.

Soon after Wang moved back to China, Shanghai’s renewed Covid lockdown in the spring of 2022 threatened to stall progress. But the startup’s budding team lived at the company’s headquarters for several months to continue their lab work.

YolTech says it has developed its own lipid nanoparticles, scoured nature to find two million CRISPR proteins and used AI and protein engineering to assess billions of possible variants of those proteins to create its own proprietary tools for gene cutting, base editing and prime editing. While US companies have raised hundreds of millions for similar tasks, YolTech did it with a comparatively modest $17 million Series A in 2022, and a

$15 million extension

in 2023.

“China-based investors tend to be more pragmatic, more willing to give you money only after they’ve seen some large animal data, at least, or preferably a clinically-validated program,” Wang said. “It’s very hard to raise money with only

in vitro

data and a good story.”

K2 Venture Partners was a returning investor in the Series B, along with Grand Flight and Yunion Healthcare Ventures, both based in China, and Decheng Capital, which has offices in Shanghai, California and New York. New investors include Green Pine Capital Partners and Tianjin Venture Capital, both based in China.

Since

treating its first patient

with ATTR in December 2023, YolTech has expanded its pipeline to a dozen programs and brought three more into the clinic.

“The efficiency of this team is truly, truly impressive,” Yao Wu, a partner at K2 Venture Partners, one of YolTech’s early investors, told Endpoints. One reason is the salaries of PhD graduates are one-third to one-half the level paid in Boston or San Diego, she said. “Also, the hours are just longer.”

Another factor is that YolTech’s clinical programs all started as investigator-initiated studies, or IITs. These small trials are approved and overseen by Chinese hospitals, rather than the nation’s drug regulators, and give startups a quick way to glimpse the safety and potential efficacy of experimental cell and gene therapies.

They’ve also allowed the company to potentially leapfrog US competitors.

In January,

YolTech began an IIT

for an

in vivo

editing therapy designed to treat beta thalassemia and sickle cell disease through an infusion of lipid nanoparticles that target the bone marrow. While numerous US drugmakers are racing to develop their own

in vivo

therapies for these two diseases, none have said when they will begin clinical trials.

And in February, YolTech

announced

the first results from an IIT of a CRISPR therapy for primary hyperoxaluria 1— five months before Cambridge-based

Arbor Biotechnologies

dosed its first patient

. YolTech is now asking the FDA to let it jump straight into a pivotal study based on its IIT data, which would catapult it even further.

“We got good positive feedback, and because this is an ultra-rare disease, the trial size is manageable,” Wang said. YolTech has also begun an IIT for the genetic condition alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency (AATD) and is preparing one for an

in vivo

CAR-T cell therapy

.

YolTech’s most advanced program uses CRISPR to break a gene, thereby reducing levels of the protein transthyretin, which causes problems for people with ATTR. It has already tested the treatment in about 25 patients in an IIT and Phase 1/2 studies with either the cardiac or nerve forms of the disease, but the company will focus on the rarer nerve form for a Phase 3.

“A large-scale cardiomyopathy trial was going to require a huge amount of resources,” Wang said. “We would rather work on other indications to show early proof-of-concept in the clinic.”

In a

press release

in March, YolTech said a single high dose reduced TTR protein by 90%, similar to data reported by Intellia. Wang said that more clinical data from the program and two others are under review at medical journals and could be published this year.

Wang said about half of the patients have been followed for at least one year, but she hopes this will be enough data to convince Chinese regulators to okay a Phase 3 — likely the country’s first for a CRISPR therapy.

She sees a big opportunity to make a one-time therapy that’s far more affordable than chronic treatments for ATTR, including Pfizer’s pill tafamidis, which

launched

with an annual cost of $225,000, and Alnylam’s siRNA drug

Amvuttra

, which costs $476,000 a year.

“That’s out of reach for most Chinese patients,” Wang said. “We did the math, and we are able to at least match tafamidis.”

Gene TherapyPhase 3Clinical Result

22 Jan 2025

A little-known Chinese biotech startup has zipped ahead of US companies in one of the gene editing field’s most competitive races.

YolTech Therapeutics

announced

Monday that it started a clinical trial of an experimental CRISPR therapy for transfusion-dependent beta thalassemia, a genetic blood disease. But rather than removing a patient’s cells and editing them in the lab, as companies in the US have already done, the Shanghai-based biotech plans to edit the cells directly in the bone marrow with a simple transfusion.

The trial is the first public disclosure globally of so-called

in vivo

editing therapy for a blood disease. It’s a potentially cheaper, easier and safer alternative to Casgevy, the sole commercial gene editing treatment made by CRISPR Therapeutics and Vertex in Boston.

Several US drugmakers, including well-funded startups and public companies, are working on

in vivo

therapies for sickle cell disease. Many believe that an

in vivo

therapy is the only way to make treatments broadly available for beta thalassemia and sickle cell disease — which can be treated with the same approach. But designing lipid nanoparticles that can reach stem cells of the bone marrow is challenging, and YolTech’s announcement that it found a solution ready for clinical testing came as a surprise.

YolTech’s beta thalassemia drug is its fourth gene editing therapy to enter clinical studies in a little over a year. Until now, its programs have mimicked ones pioneered by American companies, and the 80-person biotech hasn’t attracted much attention since it was founded in 2021.

But that’s starting to change. YolTech, which raised a $32 million Series A in December 2023, has moved at lightning speed with a fraction of the funding of other gene editing companies. CEO and co-founder Yuxuan Wu told

Endpoints News

on Tuesday that he is “looking for some potential collaborators in the United States and Europe” and took meetings with several pharma companies at the JP Morgan Healthcare Conference in San Francisco this month.

If the startup is successful, it will build upon the recent trend of biotech investors and pharma companies

turning to China as a source of new drugs

. So far, the biggest investments have centered around cancer and obesity drugs. But YolTech wants to prove that Chinese companies can compete in cutting-edge fields like gene editing, too.

“We don’t want to just stop at being considered a Chinese company. Hopefully, we will be a global company as well,” Zi Jun Emma Wang, YolTech’s chief technology officer and co-founder, told Endpoints. “It doesn’t matter where the science originates from. Good science should be good science.”

Wu cut his teeth on CRISPR a decade ago as a postdoc in Dan Bauer’s lab at Harvard and Boston Children’s Hospital, where he researched editing for blood diseases. Bauer himself was a colleague and former trainee of Boston Children’s hematologist Stuart Orkin,

whose work using gene editing to boost fetal hemoglobin

would become the trick employed in Casgevy.

Wu continued his work on CRISPR when he opened his own lab at East China Normal University in Shanghai in 2018. He also co-founded BRL Medicine, a Shanghai startup making its own CRISPR-edited cell therapies for beta thalassemia and sickle cell.

It was a tough time to be a gene editor in the country. The same year, Chinese scientist He Jiankui had announced the birth of babies whose genes were edited as embryos. The swift global condemnation put a damper on gene editing research in China and stalled BRL’s work, because hospitals didn’t want anything to do with CRISPR.

Over the next few years, Wu increasingly began to view cell-based therapies as too complex and expensive for China, an idea that’s only solidified since Casgevy’s approval in the US in 2023. The treatment is an onerous process: Doctors first harvest a patient’s bone marrow cells and ship them to a lab where they are altered with CRISPR. Before the edited cells are reinfused, the patient receives chemotherapy to clear out the old diseased cells. Casgevy costs $2.2 million per patient in the US, and that doesn’t include a lengthy hospital stay. Roughly a year after its launch, CRISPR Therapeutics said that 50 patients have had their cells collected.

In 2021, Wu co-founded YolTech to develop

in vivo

therapies as an alternative. That summer, Intellia Therapeutics

reported

the first glimpse of promising data from therapies that used lipid nanoparticles to deliver CRISPR into the liver to treat transthyretin amyloidosis. YolTech soon began working on its own therapy for that disease, as well as two other liver-targeted programs. All three are now in early-stage clinical studies.

Wang and Wu said that the

in vivo

program for beta thalassemia (which is more common in China than sickle cell disease) has always been a focus for YolTech, but the company kept quiet about its progress until November, when scientists from YolTech and East China Normal University published a preprint on

bioRxiv

describing how an

in vivo

therapy could boost fetal hemoglobin in mice.

Wang said that the nanoparticles described in the preprint are “from a couple years ago,” noting that essentially every aspect of the therapy has been optimized since then. The experimental drug, dubbed YOLT-204, uses lipid nanoparticles designed to target hematopoietic stem cells of the bone marrow to shuttle mRNA molecules encoding the company’s own base editors.

Those CRISPR tools will make a single letter change to a gene that controls production of fetal hemoglobin, boosting levels of that oxygen-ferrying protein. Crucially, the new nanoparticles are decorated with a molecule that homes in on bone marrow cells, although the company isn’t disclosing details of the key ingredient yet.

“We screened thousands of formulations,” Wang said. “I would not claim that we solved the problem, but we have a good candidate to test in the clinic.”

Gene TherapyClinical Study

08 Apr 2024

Multidrug-resistant bacterial infections that cannot be treated by any known antibiotics pose a serious global threat. A research team has now introduced a method for the development of novel antibiotics to fight resistant pathogens. The drugs are based on protein building blocks with fluorous lipid chains.

Multidrug-resistant bacterial infections that cannot be treated by any known antibiotics pose a serious global threat. In the journal Angewandte Chemie, a Chinese research team has now introduced a method for the development of novel antibiotics to fight resistant pathogens. The drugs are based on protein building blocks with fluorous lipid chains.

Antibiotics are often prescribed far too readily. In many countries they are distributed without prescriptions and administered in factory farming: prophylactically to prevent infections and enhance performance. As a result, resistance is on the rise -- increasingly against reserve antibiotics as well. The development of innovative alternatives is essential.

It is possible to learn some lessons from the microbes themselves. Lipoproteins, small protein molecules with fatty acid chains, are widely used by bacteria in their battles against microbial competitors. A number of lipoproteins have already been approved for use as drugs. The common factors among the active lipoproteins include a positive charge and an amphiphilic structure, meaning they have segments that repel fat and others that repel water. This allows them to bind to bacterial membranes and pierce through them to the interior.

A team led by Yiyun Cheng at East China Normal University in Shanghai aims to amplify this effect by replacing hydrogen atoms in the lipid chain with fluorine atoms. These make the lipid chain simultaneously water-repellant (hydrophobic) and fat-repellant (lipophobic). Their particularly low surface energy strengthens their binding to cell membranes while their lipophobicity disrupts the cohesion of the membrane.

The team synthesized a spectrum (substance library) of fluorous lipopeptides from fluorinated hydrocarbons and peptide chains. To link the two pieces, they used the amino acid cysteine, which binds them together via a disulfide bridge. The researchers screened the molecules by testing their activity against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), a widespread, highly dangerous strain of bacteria that is resistant to nearly all antibiotics. The most effective compound they found was "R6F," a fluorous lipopeptide made of six arginine units and a lipid chain made of eight carbon and thirteen fluorine atoms. To increase biocompatibility, the R6F was enclosed within phospholipid nanoparticles.

In mouse models, R6F nanoparticles were shown to be very effective against sepsis and chronic wound infections by MRSA. No toxic side effects were observed. The nanoparticles seem to attack the bacteria in several ways: they inhibit the synthesis of important cell-wall components, promoting collapse of the walls; they also pierce the cell membrane and destabilize it; disrupt the respiratory chain and metabolism; and increase oxidative stress while simultaneously disrupting the antioxidant defense system of the bacteria. In combination, these effects kill the bacteria -- other bacteria as well as MRSA. No resistance appears to develop.

These insights provide starting points for the development of highly efficient fluorous peptide drugs to treat multi-drug resistant bacteria.

100 Deals associated with East China Normal University

Login to view more data

100 Translational Medicine associated with East China Normal University

Login to view more data

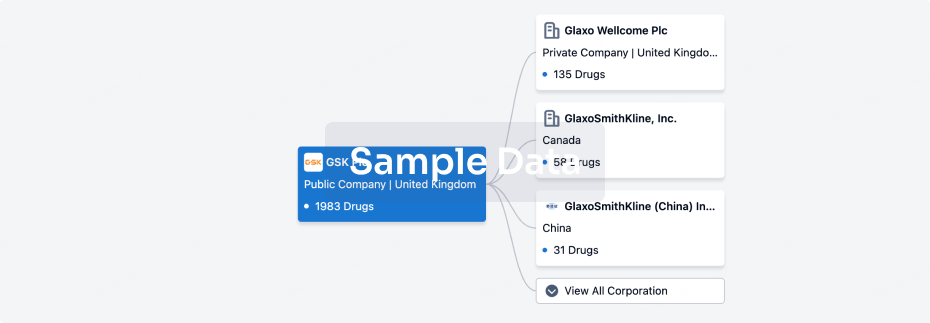

Corporation Tree

Boost your research with our corporation tree data.

login

or

Pipeline

Pipeline Snapshot as of 08 Mar 2026

The statistics for drugs in the Pipeline is the current organization and its subsidiaries are counted as organizations,Early Phase 1 is incorporated into Phase 1, Phase 1/2 is incorporated into phase 2, and phase 2/3 is incorporated into phase 3

Discovery

17

58

Preclinical

Other

6

Login to view more data

Current Projects

| Drug(Targets) | Indications | Global Highest Phase |

|---|---|---|

HC09(East China Normal University) | Neoplasms More | Preclinical |

TGF-β signaling inhibitor 8dc (East China Normal University) ( TGF-β ) | Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer More | Preclinical |

Tras-16b ( HER2 x Top I ) | HER2 Positive Breast Cancer More | Preclinical |

M-g-SN38 ( Top I ) | Neoplasms More | Preclinical |

BW-710 ( FGFR2 ) | Neoplasms More | Preclinical |

Login to view more data

Deal

Boost your decision using our deal data.

login

or

Translational Medicine

Boost your research with our translational medicine data.

login

or

Profit

Explore the financial positions of over 360K organizations with Synapse.

login

or

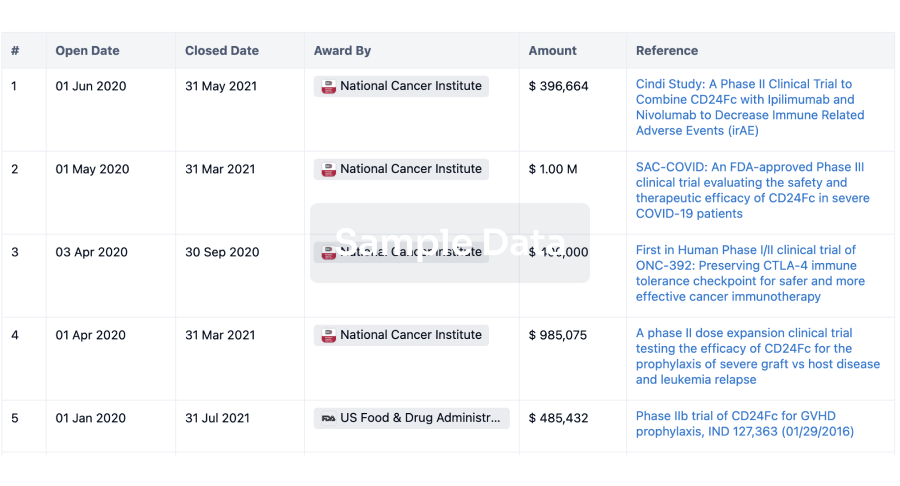

Grant & Funding(NIH)

Access more than 2 million grant and funding information to elevate your research journey.

login

or

Investment

Gain insights on the latest company investments from start-ups to established corporations.

login

or

Financing

Unearth financing trends to validate and advance investment opportunities.

login

or

AI Agents Built for Biopharma Breakthroughs

Accelerate discovery. Empower decisions. Transform outcomes.

Get started for free today!

Accelerate Strategic R&D decision making with Synapse, PatSnap’s AI-powered Connected Innovation Intelligence Platform Built for Life Sciences Professionals.

Start your data trial now!

Synapse data is also accessible to external entities via APIs or data packages. Empower better decisions with the latest in pharmaceutical intelligence.

Bio

Bio Sequences Search & Analysis

Sign up for free

Chemical

Chemical Structures Search & Analysis

Sign up for free