Request Demo

Last update 08 May 2025

Fibrinogen x fibrin

Last update 08 May 2025

Basic Info

Related Targets |

Related

1

Drugs associated with Fibrinogen x fibrinTarget |

Mechanism Fibrinogen modulators [+1] |

Active Org. |

Originator Org. |

Active Indication |

Inactive Indication |

Drug Highest PhaseApproved |

First Approval Ctry. / Loc. United States |

First Approval Date04 Jun 2021 |

3

Clinical Trials associated with Fibrinogen x fibrinNCT04586062

Sponsor Initiated Expanded Access Protocol, Intermediate-Size Patient Population

The purpose of this protocol is to provide compassionate use of Kedrion Human Plasminogen Ophthalmologic Drops to an expanded population of patients diagnosed with ligneous conjunctivitis associated with type I Plasminogen deficiency until product licensure, and/or until a new clinical trial is available and the patients in treatment under Expanded Access are eligible to participate in the new trial.

Start Date- |

Sponsor / Collaborator |

NCT03265171

A Single-patient Study of Repeat-dose Administration of ProMetic Plasminogen (Human) Intravenous Infusion in an Adult With Hypoplasminogenemia

These are single-patient studies with repeat-dose administration of ProMetic Plasminogen IV infusion in one adult and one child with hypoplasminogenemia. These patients are under treatment to address wound healing and obstructions.

Start Date- |

Sponsor / Collaborator |

EUCTR2015-005490-20-NO

A Phase 2/3, Open-Label, Repeat-Dose Study of the Pharmacokinetics, Efficacy, and Safety of ProMetic Plasminogen Intravenous Infusion in Subjects with Hypoplasminogenemia

Start Date29 Jun 2016 |

Sponsor / Collaborator |

100 Clinical Results associated with Fibrinogen x fibrin

Login to view more data

100 Translational Medicine associated with Fibrinogen x fibrin

Login to view more data

0 Patents (Medical) associated with Fibrinogen x fibrin

Login to view more data

3,146

Literatures (Medical) associated with Fibrinogen x fibrin01 Jun 2025·Biofilm

Early fibrin biofilm development in cardiovascular infections

Article

Author: Koenderink, Gijsje H ; Kooiman, Klazina ; Lattwein, Kirby R ; Hong, Jane ; Oukrich, Safae ; de Maat, Moniek P M ; Slotman, Johan A ; Leon-Grooters, Mariël ; van Wamel, Willem J B ; van Cappellen, Wiggert A

01 May 2025·Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy

The role of thrombin in the paradoxical interplay of cancer metastasis and the vascular system: A driving dynamic

Review

Author: Basbinar, Yasemin ; Bayrak, Serdar ; Bayrak, Ozge ; Alper, Meltem

14 Apr 2025·ChemBioChem

Unveiling the Architecture of Human Fibrinogen: A Full‐Length Structural Model

Article

Author: Borthagaray, Graciela ; Paulino, Margot ; Cantero, Jorge ; Medeiros, Romina

3

News (Medical) associated with Fibrinogen x fibrin25 Dec 2023

Thrombin is a crucial enzyme in the human body that plays a vital role in the blood clotting process, known as coagulation. It is produced from its precursor, prothrombin, and is activated in response to injury or damage to blood vessels. Thrombin acts as a catalyst in the conversion of fibrinogen to fibrin, forming a mesh-like structure that helps in the formation of blood clots to prevent excessive bleeding. Additionally, thrombin also activates other factors involved in the coagulation cascade, amplifying the clotting response. Its precise regulation is essential to maintain the delicate balance between clot formation and prevention of unwanted clotting within the body.

The development of thrombin inhibitors has been a significant advancement in the field of medicine. The first direct thrombin inhibitor (DTI) was hirudin, which became more easily available with genetic engineering. DTIs have undergone rapid development since the 90s. Before the use of DTIs, the therapy and prophylaxis for anticoagulation had stayed the same for over 50 years with the use of heparin derivatives and warfarin.

The analysis of the current competitive landscape and future development of target thrombin reveals several key findings. Grifols SA, China National Pharmaceutical Group Co., Ltd., and Hualan Biological Engineering, Inc. are among the companies growing fastest under this target, with Grifols SA having the highest stage of development. Hemorrhage is the most common indication for approved drugs, followed by indications such as hemophilia B, thrombosis, and venous thromboembolism. Non-recombinant coagulation factors are progressing rapidly, indicating intense competition around innovative drugs. China is developing rapidly under this target, with the highest number of approved drugs. However, further research and development are needed to explore the potential of inactive drugs in various countries/locations. Overall, the target thrombin presents opportunities for companies and researchers to develop effective treatments for various indications related to blood clotting disorders.

How do they work?Thrombin inhibitors are a type of medication that specifically target and inhibit the activity of thrombin, which is a key enzyme involved in blood clotting. Thrombin is responsible for converting fibrinogen into fibrin, which forms a mesh-like structure to help stop bleeding by forming blood clots. However, excessive or inappropriate blood clotting can lead to serious conditions such as deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, or stroke.

Thrombin inhibitors work by binding to thrombin and preventing its enzymatic activity, thereby reducing the formation of blood clots. They can be classified into two main types: direct thrombin inhibitors and indirect thrombin inhibitors.

Direct thrombin inhibitors directly bind to and inhibit the active site of thrombin, preventing its ability to convert fibrinogen into fibrin. Examples of direct thrombin inhibitors include dabigatran and argatroban.

Indirect thrombin inhibitors, on the other hand, work by targeting other molecules in the blood clotting cascade to indirectly inhibit thrombin activity. One example of an indirect thrombin inhibitor is heparin, which enhances the activity of antithrombin III, a natural inhibitor of thrombin.

Thrombin inhibitors are commonly used in the prevention and treatment of various thrombotic disorders, such as deep vein thrombosis, atrial fibrillation, and pulmonary embolism. They can also be used during certain surgical procedures to reduce the risk of blood clots. However, it is important to closely monitor patients receiving thrombin inhibitors, as they can increase the risk of bleeding.

List of thrombin InhibitorsThe currently marketed thrombin inhibitors include:

Human prothrombin complex (Guangdong Shuanglin)Human prothrombin complex (Tonrol)Human prothrombin complex (Chengdu Rongsheng)Human prothrombin complex (Boya Bio)Human Prothrombin Complex (Guangdong Wellen Biological Pharmaceutical)Human prothrombin complex(Sinopharm Group Shanghai Blood Products)Human Antithrombin III(Hemarus Therapeutics Ltd.)Human prothrombin complex(CSL bering)Human prothrombin complex(LFB Biotechnologies SASU)Human Prothrombin Complex(Harbin Pacific Biopharmaceutical)For more information, please click on the image below.

What are thrombin inhibitors used for?Thrombin inhibitors are commonly used in the prevention and treatment of various thrombotic disorders, such as deep vein thrombosis, atrial fibrillation, and pulmonary embolism. For more information, please click on the image below to log in and search.

How to obtain the latest development progress of thrombin inhibitors?In the Synapse database, you can keep abreast of the latest research and development advances of thrombin inhibitors anywhere and anytime, daily or weekly, through the "Set Alert" function. Click on the image below to embark on a brand new journey of drug discovery!

06 Nov 2023

Factor Xa, a trypsin-like serine protease, is situated at the critical juncture between the intrinsic and extrinsic pathways, catalyzing the conversion of prothrombin to thrombin, and hence plays a pivotal role in the final common pathway of the cascade and has become an important target in the discovery and development of new anticoagulants. Factor Xa is a key protease of the coagulation pathway whose activity is known to be in part modulated by binding to factor Va and sodium ions.

Blood coagulation involves a complex cascade of enzymatic reactions, ultimately generating fibrin, the basis of all blood clots. This cascade is comprised of two arms, the intrinsic and extrinsic pathways which converge at factor Xa to form the common pathway. Factor Xa activates prothrombin to thrombin, which in turn catalyzes the conversion of fibrinogen to fibrin.

Due to its significance in the coagulation process, Factor Xa has become an important target for pharmaceutical interventions, with the development of Factor Xa inhibitors that can help prevent and treat thrombotic disorders.

Factor Xa Competitive LandscapeAccording to Patsnap Synapse, as of 13 Oct 2023, there are a total of 126 factor Xa drugs worldwide, from 124 organizations, covering 66 indications, and conducting 1448 clinical trials.

👇Please click on the picture link below for free registration or login directly if you have freemium accounts, you can browse the latest research progress on drugs , indications, organizations, clinical trials, clinical results, and drug patents related to this target.

Based on the analysis of the data provided, Pfizer Inc. is the company with the highest number of drugs in the approved phase under the target factor Xa. The indications with the most approved drugs are Venous Thrombosis, Venous Thromboembolism, and Pulmonary Embolism. Small molecule drugs and chemical drugs are progressing most rapidly under the current targets. The European Union, the United States, and Japan are the countries/locations developing fastest under the target factor Xa. China also shows progress with drugs in the approved and preclinical phases. Overall, the competitive landscape for target factor Xa is dynamic, with multiple companies and drug types involved in the research and development of drugs for various indications. The future development of target factor Xa is expected to continue with a focus on improving treatment options for thrombotic and cardiovascular conditions.

Key drug:RivaroxabanRivaroxaban is a small molecule drug that targets factor Xa, an enzyme involved in blood clotting. It has been approved for use in various therapeutic areas including infectious diseases, respiratory diseases, nervous system diseases, and cardiovascular diseases. The drug is indicated for the treatment of thrombosis, peripheral arterial occlusive disease, systemic embolism, stroke, embolism, atrial fibrillation, coronary artery disease, peripheral arterial disease, pulmonary embolism, venous thromboembolism, venous thrombosis, and even COVID-19.

👇Please click on the image below to directly access the latest data (R&D Status | Core Patent | Clinical Trial | Approval status in Global countries) of this drug.

The originator organization of Rivaroxaban is Bayer AG, a multinational pharmaceutical company. The drug has reached the highest phase of approval both globally and in China. It received its first approval in Canada in September 2008, marking its initial entry into the market.

In terms of regulation, Rivaroxaban has undergone priority review and fast track processes. These regulatory pathways expedite the approval process for drugs that address unmet medical needs or provide significant advancements in treatment options.

Rivaroxaban's approval for multiple therapeutic areas and indications highlights its versatility and potential impact in various medical conditions. Its ability to target factor Xa makes it a valuable tool in preventing and treating blood clot-related disorders. The drug's approval in China and other countries further demonstrates its global recognition and acceptance.

As an expert in the pharmaceutical industry, analyzing the information provided can help identify the drug's market potential and opportunities for business development. The wide range of therapeutic areas and indications suggests a broad patient population that could benefit from Rivaroxaban. Additionally, the drug's fast track and priority review designations indicate regulatory support and potential for accelerated market entry.

Overall, Rivaroxaban's approval, target specificity, and broad therapeutic applications position it as a significant player in the pharmaceutical industry. Its originator organization, Bayer AG, has successfully developed and brought this drug to market, showcasing their expertise in the field. As the drug continues to be used in various medical conditions, further research and development may uncover additional indications and expand its market reach.

BetrixabanBetrixaban is a small molecule drug that targets factor Xa and is primarily used in the treatment of cardiovascular diseases. Specifically, it is indicated for the treatment of venous thromboembolism. The drug was developed by Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Inc., and it reached the highest phase of clinical trials, which is Phase 3.

👇Please click on the image below to directly access the latest data (R&D Status | Core Patent | Clinical Trial | Approval status in Global countries) of this drug.

Betrixaban received its first approval globally in June 2017, with the United States being the first country to approve it. The drug was granted Fast Track designation, which is a regulatory process designed to expedite the development and review of drugs that address unmet medical needs.

As a small molecule drug, Betrixaban is likely to have a well-defined chemical structure and can be easily synthesized in a laboratory setting. Its target, factor Xa, is an enzyme involved in the blood clotting process. By inhibiting factor Xa, Betrixaban can prevent the formation of blood clots, particularly in the veins.

Cardiovascular diseases, including venous thromboembolism, are a significant health concern worldwide. Venous thromboembolism refers to the formation of blood clots in the veins, which can lead to serious complications such as pulmonary embolism. Betrixaban's approval for this indication suggests that it has demonstrated efficacy and safety in clinical trials.

The fact that Betrixaban reached Phase 3 trials indicates that it has undergone extensive testing in humans to evaluate its effectiveness and safety profile. This phase typically involves large-scale studies involving thousands of patients. The successful completion of Phase 3 trials is a crucial step towards obtaining regulatory approval.

The Fast Track designation granted to Betrixaban suggests that there is a recognized need for new treatments in the field of cardiovascular diseases, particularly for venous thromboembolism. This designation allows for a more streamlined regulatory process, potentially accelerating the availability of the drug to patients.

In summary, Betrixaban is a small molecule drug developed by Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Inc. It targets factor Xa and is indicated for the treatment of venous thromboembolism, a type of cardiovascular disease. The drug has reached Phase 3 trials and received its first approval in the United States in June 2017. Its Fast Track designation highlights the need for new treatments in this therapeutic area.

28 Apr 2023

The blood protein fibrin plays a key role in stopping bleeding, but in certain circumstance it can also contribute to disease. Therein lies the challenge for developing a fibrin-targeting drug. Scientists need to figure out how to stop the disease-driving activity while also maintaining the protein’s very important role in clotting and coagulation.

Therini Bio is developing a drug designed to selectively block fibrin, potentially addressing inflammation behind neurological disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease as well as some eye disorders. The South San Francisco-based biotech’s research has yielded encouraging preclinical data. As the biotech transitions into a clinical-stage company, it has raised $36 million from a syndicate that includes the investment arms of Merck, Sanofi, and Eli Lilly.

Therini is based on the research of Katerina Akassoglou, an investigator at the Gladstone Institutes at the University of California San Francisco, and formerly of the University of California San Diego. Her work focuses on the role blood proteins have on nervous system disorders. Research from Akassoglou and her colleagues published in 2018 in Nature Reviews Neuroscience and Nature Immunology described how fibrin is associated with toxic inflammation and neuron damage in Alzheimer’s, multiple sclerosis, and other neurological disorders. In these diseases, disruption to the blood-brain barrier allows fibrin to enter the brain and spark disease-driving inflammatory effects there.

How a protein that is helpful can also contribute to disease is a matter of timing, said Therini President and CEO Michael Quigley, who is also a venture partner at SV Health Investors was previously an executive at Gilead Sciences. The formation of fibrin is a normal bodily process, and it happens frequently in people who exercise regularly. For example, runners experience tiny bleeds in tissues that are stopped by clot-forming fibrin, Quigley said. But after fibrin performs its healing role, it goes away. Fibrin clots are broken down by enzymes in the blood.

Problems can develop when fibrin doesn’t go away, Quigley said. Low levels of the fibrin-busting enzymes result in the clotting protein staying around longer. In some diseases, there are additional inhibitors to the breakdown process. When blood clots persist, they contribute to inflammation in the body.

“In settings of disease, the breakdown of the clot does not happen,” Quigley said. “Persistence is believed to be a driver of disease.”

Fibrin’s pro-inflammatory role in a wide variety of diseases has been known for some time, Quigley said. In the 1980s, research efforts included thrombolytics—drugs that break down blood clots. But long-term use of these drugs raised bleeding risks, making them unsuitable as therapeutic interventions, he said.

Therini’s proposed solution is THN391, an antibody that blocks disease-driving fibrin without diminishing the protein’s blood clotting properties. Fibrin forms from another protein called fibrinogen. The epitope, the part of the protein to which Therini’s antibody binds, is not exposed in fibrinogen, Quigley said. But this epitope presents itself when fibrinogen converts to fibrin. THN391 targets only this epitope.

“What is unique, we can specifically target the chronic inflammatory disease driving aspect of fibrin while sparing the coagulation aspect,” Quigley said.

In preclinical research, THN391 was able to cross the blood-brain barrier to block disease-driving fibrin. Results also showed the Therini drug led to reductions in hallmarks of multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer’s, and retinal diseases, Quigley said. Just as important, targeting the particular fibrin epitope did not diminish the protein’s role in clotting and coagulation.

Therini scientists believe THN391’s fibrin-targeting approach will apply to retinal diseases characterized by inflammation, such as diabetic macular edema. The company will pursue neurodegeneration and eye disorders in parallel, Quigley said. Additional research includes fibrin tethering, in which an anti-fibrin antibody is used to also deliver a drug payload to disease sites. Delivering a therapeutic agent on top of blocking fibrin could be beneficial in treating disease, though this research is still in the discovery stage, Quigley said. With the new capital, the startup will advance THN391 into Phase 1 testing. Safety and proof of mechanism data are expected by the end of next year.

Therini was initially named MedaRed. In 2019, the Gladstone spinout raised $6.5 million in seed financing led by Dementia Discovery Fund and Dolby Family Ventures. The following year, MedaRed changed its name to Therini Bio. In 2021, the startup raised another $17 million in a seed round extension led by SV Health Investors’ Impact Medicine Fund, MRL Ventures, and Sanofi Ventures.

The Series A financing was co-led by Dementia Discovery Fund, MRL Ventures Fund, the therapeutics-focused corporate venture fund of Merck, Sanofi Ventures, and Impact Medicine Fund. Eli Lilly joined as a new investor in the new round, which included participation of all earlier investors. Therini says the latest financing brings the total amount raised since inception to $62 million.

Image by Therini Bio

Analysis

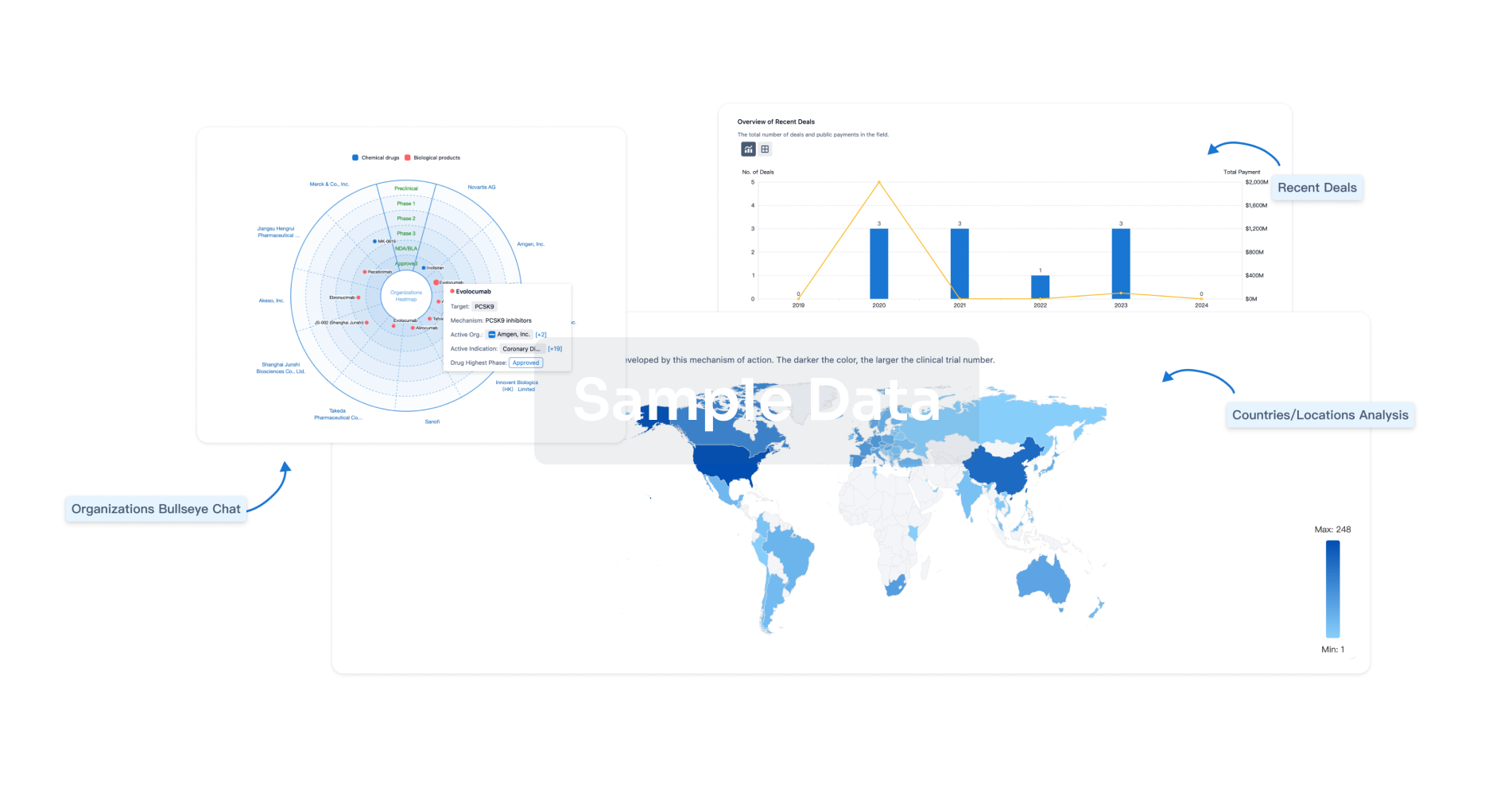

Perform a panoramic analysis of this field.

login

or

AI Agents Built for Biopharma Breakthroughs

Accelerate discovery. Empower decisions. Transform outcomes.

Get started for free today!

Accelerate Strategic R&D decision making with Synapse, PatSnap’s AI-powered Connected Innovation Intelligence Platform Built for Life Sciences Professionals.

Start your data trial now!

Synapse data is also accessible to external entities via APIs or data packages. Empower better decisions with the latest in pharmaceutical intelligence.

Bio

Bio Sequences Search & Analysis

Sign up for free

Chemical

Chemical Structures Search & Analysis

Sign up for free