Request Demo

Can taking anti-depressants and anti-anxiety drugs lower your intelligence?

21 March 2025

Introduction to Anti-depressants and Anti-anxiety Drugs

Anti-depressants and anti-anxiety drugs are medications widely used across various psychiatric conditions, including depression, anxiety disorders, and related mood disturbances. These drugs are critical in managing symptoms that affect daily life, work productivity, and overall well-being. Their usage, however, has raised questions regarding potential cognitive side effects, particularly whether long-term use may lower one’s intelligence. The answer to this inquiry requires a multi-dimensional evaluation of the pharmacological properties of these drugs, the current scientific evidence on their cognitive impacts, and an in-depth understanding of what we mean by “intelligence.”

Types of Medications

The class of anti-depressants includes several types, such as:

- Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs): Medications like fluoxetine and sertraline function by increasing serotonin levels in the synaptic cleft.

- Serotonin-Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors (SNRIs): These drugs target both serotonin and norepinephrine systems and are used in conditions where a dual mechanism may better alleviate symptoms.

- Tricyclic Antidepressants (TCAs): Older agents, which not only affect monoamine transmission but also have anticholinergic properties that could influence cognition.

- Atypical Antidepressants: Including agents with unique mechanisms such as bupropion, which is known to have a somewhat stimulating profile.

Anti-anxiety drugs, often used to treat generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and other anxiety-related conditions, generally include:

- Benzodiazepines: A.k.a. classic anti-anxiety agents such as diazepam or lorazepam, these medications act on the gamma‐aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptor complex and can cause sedation and impair attention acutely.

- Non-Benzodiazepine Anxiolytics: Newer agents such as buspirone that have a distinct mechanism by modulating serotonin receptors may present with a different cognitive profile compared to benzodiazepines.

Mechanisms of Action

The therapeutic effects of these medications are driven by their ability to alter neurotransmitter levels and receptor activity in the brain. For example, SSRIs increase the extracellular concentration of serotonin, leading over time to adaptive changes in receptor sensitivity and neuroplastic processes. Similarly, benzodiazepines enhance GABAergic activity leading to a potent inhibitory effect which reduces anxiety, but also can transiently impair certain cognitive functions such as attention and memory.

These mechanisms, while central to alleviating mood and anxiety symptoms, may also, in essence, affect cognitive processing—as a result of their primary or secondary actions on various brain circuits involved in cognition. However, the picture is complex: while some drugs with sedative properties might transiently slow information processing (therefore impacting reaction time or attention), other anti-depressants have been linked to improved neuroplasticity and modest pro-cognitive effects in patients who experience cognitive impairments as part of their depressive symptoms.

Cognitive Function and Intelligence

Understanding the potential effects of anti-depressants and anti-anxiety drugs on intelligence requires first an appreciation of what cognitive function and intelligence truly mean. Cognitive functions are multifaceted and encompass a wide range of mental abilities, while intelligence is generally regarded as an aggregate of one’s cognitive capacities.

Definition and Components of Intelligence

Intelligence is a comprehensive construct that typically includes various components such as:

- Memory (short-term and long-term): The ability to encode, store, and retrieve information.

- Executive Functions: Including planning, problem-solving, decision-making, inhibition, and cognitive flexibility.

- Attention and Processing Speed: The capacity to focus, maintain concentration, and process incoming information quickly.

- Verbal Reasoning and Language Abilities: The skills associated with understanding, verbalizing, and manipulating language.

- Abstract and Logical Thinking: The ability to consider complex ideas or relationships that are not immediately apparent.

This broad understanding suggests that “lowering your intelligence” would in principle require a significant and permanent deterioration across these multiple domains rather than a transient impairment in one or two aspects.

Factors Affecting Cognitive Function

Several factors contribute to overall cognitive function and, by extension, performance on measures of intelligence:

- Genetic and Biological Factors: Inherent brain structure, neurochemical balance, and synaptic plasticity.

- Developmental and Environmental Influences: Education, stress, nutrition, and social interactions contribute substantially to cognitive reserve.

- Medical and Pharmacological Interventions: Medications, particularly those affecting neurotransmitter systems, can influence cognition either positively or negatively.

- Acute State vs. Chronic Effects: While several drugs might acutely impair attention or processing speed due to sedation, chronic treatment may lead to adaptation or even improvements in cognition in the context of underlying psychiatric dysfunction.

Impact of Anti-depressants and Anti-anxiety Drugs on Cognitive Function

The core question “Can taking anti-depressants and anti-anxiety drugs lower your intelligence?” needs to be interpreted through the lens of current evidence on cognitive function rather than a simplistic “yes” or “no”. Research from synapse sources provides a nuanced view.

Evidence from Clinical Studies

A range of clinical studies and meta-analyses have examined the impact of anti-depressant and anti-anxiety medications on various domains of cognition. Here are some findings from reliable and structured research outputs:

- Mixed Cognitive Outcomes: Certain studies indicate that some antidepressants, particularly SSRIs, may not only avoid impairing cognitive function but could even exert mild pro-cognitive effects. For instance, a study assessing the effect of fluoxetine found that some cognitive functions improved over the course of treatment in depressed patients. Moreover, large-scale epidemiological studies suggest that antidepressant use does not significantly modify the long-term cognitive trajectory in older adults.

- Sedative and Short-term Effects: Medications like benzodiazepines are associated with sedation, impaired attention, and slowed psychomotor speed in the short term. These deficits, however, are usually reversible once the medication is tapered or discontinued, or the acute effects wear off.

- No Evidence of Permanent “Lowering” of Intelligence: No consistent or robust evidence indicates that the routine and long-term use of anti-depressants or anti-anxiety drugs results in a permanent lowering of intelligence. Instead, minor cognitive side effects are often transient or emerge in certain populations (e.g., older adults with polypharmacy) but are not equivalent to an overall loss of intellectual capacity.

- Differential Impact Based on Drug Class and Dosage: The literature further indicates that the adverse cognitive impacts are dose-dependent and vary significantly with specific drug classes and individual factors. For instance, TCAs with anticholinergic properties might cause more noticeable short-term memory impairments compared to SSRIs, which generally have a milder cognitive profile.

- Cognition as a Treatment Outcome: In many clinical trials, cognitive outcomes are measured as secondary endpoints. Some antidepressants appear to improve aspects of cognitive function such as working memory and processing speed by alleviating the depressive symptoms that are themselves associated with cognitive impairment. This means that, in some patient groups, the cognitive benefits derived from treating depression can outweigh any intrinsic cognitive side effects of the medication itself.

Overall, while some drugs can cause temporary slowing of cognitive processes or sedation—effects that might erroneously be interpreted as a lowering of overall cognitive ability—the evidence does not support a direct causal link to a permanent reduction in intelligence.

Potential Mechanisms of Cognitive Impact

From a mechanistic perspective, several pathways account for how these medications interact with cognitive processes:

- Neurotransmitter Modulation: Anti-depressants primarily act on monoaminergic systems (serotonin, noradrenaline, dopamine) which are implicated in mood regulation and cognitive functions. In patients with depressive symptoms, these medications can lead to improvements in neurocognitive function over time by enhancing synaptic plasticity and promoting neurogenesis—particularly in brain regions like the hippocampus.

- Sedation and Alertness: Benzodiazepines, and to a lesser extent some antidepressants with sedative properties, potentiate GABAergic inhibition. This can reduce central nervous system arousal, leading to slowed reaction times, decreased attentional capacity, and impaired working memory when taken at higher doses. However, these effects are typically reversible and are dependent on dosage and timing relative to testing.

- Cholinergic Side Effects: Certain older antidepressants with anticholinergic effects can temporarily impair memory and attention because acetylcholine is crucial for cognitive processes. Such drug-induced disruptions are usually reversible once the drug is metabolized and do not indicate permanent changes in intellectual capability.

- Interaction with Underlying Disorders: It is also important to emphasize that depression and anxiety disorders themselves are associated with cognitive dysfunction. When treated appropriately, the medication may help restore a more optimal cognitive function rather than degrade it, thereby indirectly improving performance on cognitive tasks.

- Adaptive Brain Mechanisms: Over the long term, the brain often adapts to the presence of these drugs. Neuroimaging and neuropsychological research indicate that while acute dosing may show transient impairments, chronic treatment combined with therapeutic interventions (e.g., cognitive behavioral therapy) can lead to normalization or even improvements in neural circuits underlying cognitive function.

In summary, the mechanisms by which anti-depressants and anti-anxiety drugs can impact cognition are multifaceted. They include potential short-term impairments due to sedative effects and anticholinergic activity, contrasted with long-term adaptations and even cognitive enhancements that accompany symptom relief in mood disorders.

Managing Cognitive Side Effects

Even though the evidence does not support a general decrement in overall intelligence from the use of these medications, managing cognitive side effects is a real-world concern for clinicians. Various strategies have been developed to address any unwanted cognitive consequences associated with anti-depressant and anti-anxiety drug use.

Strategies for Monitoring and Management

- Regular Cognitive Assessments: Implementing routine neuropsychological testing can help monitor changes in attention, memory, executive functions, and other cognitive domains over the course of treatment. Tests can include standardized measures of working memory and executive functions, which help in early detection of potential impairments.

- Dose Adjustments and Timing: Adjusting the dose or timing of the medication can mitigate acute cognitive side effects. For instance, taking benzodiazepines at a lower dose or only during periods of acute anxiety may reduce sedative effects that interfere with cognitive performance.

- Individualized Treatment Plans: Since the impact of these drugs varies by individual, a personalized approach that factors in genetic predispositions, baseline cognitive status, and concurrent use of other medications (polypharmacy) is essential. This tailored approach ensures that any cognitive impairments are promptly identified and addressed by modifying treatment regimens.

- Adjunctive Cognitive Remediation Therapies: Coupling pharmacotherapy with cognitive remediation or cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) can help alleviate residual cognitive deficits and improve daily functioning. This dual-strategy is especially beneficial in patients whose cognitive performance remains suboptimal despite improvement in mood or anxiety symptoms.

- Monitoring for Anticholinergic Load: For patients on medications with significant anticholinergic properties, clinicians can monitor the cumulative anticholinergic load, which is associated with cognitive impairment in the elderly. Reducing the overall anticholinergic burden by switching to medications with lower anticholinergic effects can be very helpful.

- Patient Education and Lifestyle Interventions: Educating patients about potential cognitive side effects and advising on lifestyle modifications, such as regular exercise, adequate sleep, and cognitive training exercises, can support overall brain health. These interventions help maintain cognitive reserve and prevent any potential long-term adverse effects.

Alternative Treatments and Approaches

- Non-Pharmacological Approaches: When appropriate, non-pharmacological treatments such as psychotherapy, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, and stress-reduction techniques may be considered as primary or adjunct treatments. These strategies can often improve mood and anxiety without the risk of medication-induced cognitive impairment.

- Switching Medication Classes: If a patient experiences significant cognitive side effects, clinicians might consider transitioning to a different class of medication with a more favorable cognitive side effect profile. For example, switching from a highly sedative benzodiazepine to a non-benzodiazepine anxiolytic like buspirone may help.

- Combination Therapy with Cognitive Enhancers: In some cases, the addition of cognitive enhancing agents (e.g., certain cholinesterase inhibitors) may be considered if cognitive impairment persists. Although not common, such combinations have been explored to optimize cognitive outcomes in populations with comorbid depression and cognitive dysfunction.

- Regular Follow-up and Adjustment: Continuous follow-up with both subjective patient feedback and objective cognitive assessments will ensure that any emerging deficits are quickly managed. Clinicians should be proactive in making dose adjustments or modifying treatment plans as needed to maintain optimal cognitive functioning.

Conclusions and Future Research

Summary of Findings

The overarching question of whether taking anti-depressants and anti-anxiety drugs can lower your intelligence is best addressed by understanding the complexity of cognitive functions and their modulation by pharmacotherapy. The following points summarize the insights from various perspectives:

- Multifactorial Nature of Cognition: Intelligence is derived from an interplay of multiple cognitive domains—including memory, executive function, attention, and processing speed—which can be transiently influenced by medications without constituting an overall decline in intellectual capacity.

- Transient vs. Permanent Effects: Clinical evidence suggests that while some anti-depressants and anti-anxiety drugs (especially those with sedative or anticholinergic properties) can produce short-term impairments in attention, processing speed, and memory, these effects are generally reversible and do not imply a permanent lowering of intelligence.

- Potential for Cognitive Improvement: In patients suffering from depression or anxiety, treatment often leads to an improvement in cognitive function as the underlying psychiatric symptoms are alleviated. This relief can result in better cognitive performance overall, counterbalancing any minor drug-induced impairments.

- Individual Variability and Dose Dependency: The degree of cognitive impact is variable and highly dependent on the specific medication, dosage, individual patient physiology, and the presence of underlying cognitive deficits. Careful management, monitoring, and adjustment of treatment regimens mitigate potential adverse effects.

- Management Strategies are Effective: Clinical strategies including personalized dosing, cognitive remediation therapies, regular neuropsychological assessments, and patient education have been shown to effectively manage any cognitive side effects, ensuring that long-term intelligence is not compromised.

Areas for Further Study

While current evidence overwhelmingly suggests that anti-depressants and anti-anxiety drugs do not permanently lower intelligence, several areas warrant further research:

- Longitudinal Studies in Diverse Populations: More long-term studies with diverse patient populations are needed to conclusively determine the chronic effects of these medications on overall cognitive function and to assess whether any subgroups may be at increased risk of persistent cognitive deficits.

- Mechanistic Research on Neuroplasticity: Further investigations into the molecular and cellular mechanisms, particularly the role of neuroplasticity and neurogenesis in response to pharmacotherapy, will help elucidate how these drugs contribute to cognitive improvements as well as transient impairments.

- Comparative Effectiveness Studies: Direct comparisons between different classes of anti-depressants and anti-anxiety drugs in terms of cognitive side effects could help guide clinicians in selecting medications with the most favorable cognitive profiles.

- Exploration of Combination Therapies: Research into the combined effects of pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions on cognitive outcomes can pave the way for more comprehensive treatment plans, especially for those prone to cognitive side effects.

- Impact on Specific Cognitive Domains: Detailed neuropsychological assessments that isolate effects on various components of intelligence (e.g., verbal memory, executive function, attention) will provide clearer insights into the cognitive fingerprint of these medications.

- Patient-Centered Outcomes: Future studies should incorporate patient-reported outcomes regarding subjective cognitive changes, as well as objective clinical measures, to bridge the gap between laboratory findings and real-world functional status.

In conclusion, while some anti-depressants and anti-anxiety medications—particularly those with sedative or anticholinergic properties—can lead to temporary cognitive impairments in certain domains, the current body of evidence does not support the notion that these drugs permanently lower intelligence. For most patients, the benefits of symptom relief and improved mood far outweigh any transient cognitive drawbacks, and targeted management strategies further minimize these effects. Future research aimed at refining our understanding of the drug-induced modulation of cognitive processes will be instrumental in optimizing treatment regimens and ensuring that patients receive both effective psychiatric care and the preservation of cognitive integrity.

By adopting a general-specific-general analytical approach, we appreciate that the impact of these medications on cognitive function is complex and multifactorial. At a broad level, anti-depressants and anti-anxiety drugs serve a critical role in mitigating psychiatric symptoms. In specific terms, while some cognitive side effects are observed, they are typically transient, dosage-dependent, and manageable. Generalizing these findings, there is no conclusive evidence that these medications lead to a permanent lowering of intelligence, particularly when treatment is carefully tailored and monitored. As research progresses, further refinements in pharmacotherapy and adjunctive cognitive interventions are expected to ensure optimal cognitive as well as emotional outcomes for patients.

Ultimately, based on the available synapse-supported references, taking anti-depressants and anti-anxiety drugs does not equate to permanently lowering one’s intelligence. Instead, these medications may transiently affect certain cognitive processes; however, proper management, individualized treatment plans, and the overall beneficial effects on mood and anxiety contribute to improved cognitive function in the long run rather than impairing overall intellectual capacity. Continued research and systematic assessments are essential to further inform both clinicians and patients, thereby optimizing treatment strategies that safeguard cognitive health while addressing psychiatric disorders.

Anti-depressants and anti-anxiety drugs are medications widely used across various psychiatric conditions, including depression, anxiety disorders, and related mood disturbances. These drugs are critical in managing symptoms that affect daily life, work productivity, and overall well-being. Their usage, however, has raised questions regarding potential cognitive side effects, particularly whether long-term use may lower one’s intelligence. The answer to this inquiry requires a multi-dimensional evaluation of the pharmacological properties of these drugs, the current scientific evidence on their cognitive impacts, and an in-depth understanding of what we mean by “intelligence.”

Types of Medications

The class of anti-depressants includes several types, such as:

- Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs): Medications like fluoxetine and sertraline function by increasing serotonin levels in the synaptic cleft.

- Serotonin-Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors (SNRIs): These drugs target both serotonin and norepinephrine systems and are used in conditions where a dual mechanism may better alleviate symptoms.

- Tricyclic Antidepressants (TCAs): Older agents, which not only affect monoamine transmission but also have anticholinergic properties that could influence cognition.

- Atypical Antidepressants: Including agents with unique mechanisms such as bupropion, which is known to have a somewhat stimulating profile.

Anti-anxiety drugs, often used to treat generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and other anxiety-related conditions, generally include:

- Benzodiazepines: A.k.a. classic anti-anxiety agents such as diazepam or lorazepam, these medications act on the gamma‐aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptor complex and can cause sedation and impair attention acutely.

- Non-Benzodiazepine Anxiolytics: Newer agents such as buspirone that have a distinct mechanism by modulating serotonin receptors may present with a different cognitive profile compared to benzodiazepines.

Mechanisms of Action

The therapeutic effects of these medications are driven by their ability to alter neurotransmitter levels and receptor activity in the brain. For example, SSRIs increase the extracellular concentration of serotonin, leading over time to adaptive changes in receptor sensitivity and neuroplastic processes. Similarly, benzodiazepines enhance GABAergic activity leading to a potent inhibitory effect which reduces anxiety, but also can transiently impair certain cognitive functions such as attention and memory.

These mechanisms, while central to alleviating mood and anxiety symptoms, may also, in essence, affect cognitive processing—as a result of their primary or secondary actions on various brain circuits involved in cognition. However, the picture is complex: while some drugs with sedative properties might transiently slow information processing (therefore impacting reaction time or attention), other anti-depressants have been linked to improved neuroplasticity and modest pro-cognitive effects in patients who experience cognitive impairments as part of their depressive symptoms.

Cognitive Function and Intelligence

Understanding the potential effects of anti-depressants and anti-anxiety drugs on intelligence requires first an appreciation of what cognitive function and intelligence truly mean. Cognitive functions are multifaceted and encompass a wide range of mental abilities, while intelligence is generally regarded as an aggregate of one’s cognitive capacities.

Definition and Components of Intelligence

Intelligence is a comprehensive construct that typically includes various components such as:

- Memory (short-term and long-term): The ability to encode, store, and retrieve information.

- Executive Functions: Including planning, problem-solving, decision-making, inhibition, and cognitive flexibility.

- Attention and Processing Speed: The capacity to focus, maintain concentration, and process incoming information quickly.

- Verbal Reasoning and Language Abilities: The skills associated with understanding, verbalizing, and manipulating language.

- Abstract and Logical Thinking: The ability to consider complex ideas or relationships that are not immediately apparent.

This broad understanding suggests that “lowering your intelligence” would in principle require a significant and permanent deterioration across these multiple domains rather than a transient impairment in one or two aspects.

Factors Affecting Cognitive Function

Several factors contribute to overall cognitive function and, by extension, performance on measures of intelligence:

- Genetic and Biological Factors: Inherent brain structure, neurochemical balance, and synaptic plasticity.

- Developmental and Environmental Influences: Education, stress, nutrition, and social interactions contribute substantially to cognitive reserve.

- Medical and Pharmacological Interventions: Medications, particularly those affecting neurotransmitter systems, can influence cognition either positively or negatively.

- Acute State vs. Chronic Effects: While several drugs might acutely impair attention or processing speed due to sedation, chronic treatment may lead to adaptation or even improvements in cognition in the context of underlying psychiatric dysfunction.

Impact of Anti-depressants and Anti-anxiety Drugs on Cognitive Function

The core question “Can taking anti-depressants and anti-anxiety drugs lower your intelligence?” needs to be interpreted through the lens of current evidence on cognitive function rather than a simplistic “yes” or “no”. Research from synapse sources provides a nuanced view.

Evidence from Clinical Studies

A range of clinical studies and meta-analyses have examined the impact of anti-depressant and anti-anxiety medications on various domains of cognition. Here are some findings from reliable and structured research outputs:

- Mixed Cognitive Outcomes: Certain studies indicate that some antidepressants, particularly SSRIs, may not only avoid impairing cognitive function but could even exert mild pro-cognitive effects. For instance, a study assessing the effect of fluoxetine found that some cognitive functions improved over the course of treatment in depressed patients. Moreover, large-scale epidemiological studies suggest that antidepressant use does not significantly modify the long-term cognitive trajectory in older adults.

- Sedative and Short-term Effects: Medications like benzodiazepines are associated with sedation, impaired attention, and slowed psychomotor speed in the short term. These deficits, however, are usually reversible once the medication is tapered or discontinued, or the acute effects wear off.

- No Evidence of Permanent “Lowering” of Intelligence: No consistent or robust evidence indicates that the routine and long-term use of anti-depressants or anti-anxiety drugs results in a permanent lowering of intelligence. Instead, minor cognitive side effects are often transient or emerge in certain populations (e.g., older adults with polypharmacy) but are not equivalent to an overall loss of intellectual capacity.

- Differential Impact Based on Drug Class and Dosage: The literature further indicates that the adverse cognitive impacts are dose-dependent and vary significantly with specific drug classes and individual factors. For instance, TCAs with anticholinergic properties might cause more noticeable short-term memory impairments compared to SSRIs, which generally have a milder cognitive profile.

- Cognition as a Treatment Outcome: In many clinical trials, cognitive outcomes are measured as secondary endpoints. Some antidepressants appear to improve aspects of cognitive function such as working memory and processing speed by alleviating the depressive symptoms that are themselves associated with cognitive impairment. This means that, in some patient groups, the cognitive benefits derived from treating depression can outweigh any intrinsic cognitive side effects of the medication itself.

Overall, while some drugs can cause temporary slowing of cognitive processes or sedation—effects that might erroneously be interpreted as a lowering of overall cognitive ability—the evidence does not support a direct causal link to a permanent reduction in intelligence.

Potential Mechanisms of Cognitive Impact

From a mechanistic perspective, several pathways account for how these medications interact with cognitive processes:

- Neurotransmitter Modulation: Anti-depressants primarily act on monoaminergic systems (serotonin, noradrenaline, dopamine) which are implicated in mood regulation and cognitive functions. In patients with depressive symptoms, these medications can lead to improvements in neurocognitive function over time by enhancing synaptic plasticity and promoting neurogenesis—particularly in brain regions like the hippocampus.

- Sedation and Alertness: Benzodiazepines, and to a lesser extent some antidepressants with sedative properties, potentiate GABAergic inhibition. This can reduce central nervous system arousal, leading to slowed reaction times, decreased attentional capacity, and impaired working memory when taken at higher doses. However, these effects are typically reversible and are dependent on dosage and timing relative to testing.

- Cholinergic Side Effects: Certain older antidepressants with anticholinergic effects can temporarily impair memory and attention because acetylcholine is crucial for cognitive processes. Such drug-induced disruptions are usually reversible once the drug is metabolized and do not indicate permanent changes in intellectual capability.

- Interaction with Underlying Disorders: It is also important to emphasize that depression and anxiety disorders themselves are associated with cognitive dysfunction. When treated appropriately, the medication may help restore a more optimal cognitive function rather than degrade it, thereby indirectly improving performance on cognitive tasks.

- Adaptive Brain Mechanisms: Over the long term, the brain often adapts to the presence of these drugs. Neuroimaging and neuropsychological research indicate that while acute dosing may show transient impairments, chronic treatment combined with therapeutic interventions (e.g., cognitive behavioral therapy) can lead to normalization or even improvements in neural circuits underlying cognitive function.

In summary, the mechanisms by which anti-depressants and anti-anxiety drugs can impact cognition are multifaceted. They include potential short-term impairments due to sedative effects and anticholinergic activity, contrasted with long-term adaptations and even cognitive enhancements that accompany symptom relief in mood disorders.

Managing Cognitive Side Effects

Even though the evidence does not support a general decrement in overall intelligence from the use of these medications, managing cognitive side effects is a real-world concern for clinicians. Various strategies have been developed to address any unwanted cognitive consequences associated with anti-depressant and anti-anxiety drug use.

Strategies for Monitoring and Management

- Regular Cognitive Assessments: Implementing routine neuropsychological testing can help monitor changes in attention, memory, executive functions, and other cognitive domains over the course of treatment. Tests can include standardized measures of working memory and executive functions, which help in early detection of potential impairments.

- Dose Adjustments and Timing: Adjusting the dose or timing of the medication can mitigate acute cognitive side effects. For instance, taking benzodiazepines at a lower dose or only during periods of acute anxiety may reduce sedative effects that interfere with cognitive performance.

- Individualized Treatment Plans: Since the impact of these drugs varies by individual, a personalized approach that factors in genetic predispositions, baseline cognitive status, and concurrent use of other medications (polypharmacy) is essential. This tailored approach ensures that any cognitive impairments are promptly identified and addressed by modifying treatment regimens.

- Adjunctive Cognitive Remediation Therapies: Coupling pharmacotherapy with cognitive remediation or cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) can help alleviate residual cognitive deficits and improve daily functioning. This dual-strategy is especially beneficial in patients whose cognitive performance remains suboptimal despite improvement in mood or anxiety symptoms.

- Monitoring for Anticholinergic Load: For patients on medications with significant anticholinergic properties, clinicians can monitor the cumulative anticholinergic load, which is associated with cognitive impairment in the elderly. Reducing the overall anticholinergic burden by switching to medications with lower anticholinergic effects can be very helpful.

- Patient Education and Lifestyle Interventions: Educating patients about potential cognitive side effects and advising on lifestyle modifications, such as regular exercise, adequate sleep, and cognitive training exercises, can support overall brain health. These interventions help maintain cognitive reserve and prevent any potential long-term adverse effects.

Alternative Treatments and Approaches

- Non-Pharmacological Approaches: When appropriate, non-pharmacological treatments such as psychotherapy, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, and stress-reduction techniques may be considered as primary or adjunct treatments. These strategies can often improve mood and anxiety without the risk of medication-induced cognitive impairment.

- Switching Medication Classes: If a patient experiences significant cognitive side effects, clinicians might consider transitioning to a different class of medication with a more favorable cognitive side effect profile. For example, switching from a highly sedative benzodiazepine to a non-benzodiazepine anxiolytic like buspirone may help.

- Combination Therapy with Cognitive Enhancers: In some cases, the addition of cognitive enhancing agents (e.g., certain cholinesterase inhibitors) may be considered if cognitive impairment persists. Although not common, such combinations have been explored to optimize cognitive outcomes in populations with comorbid depression and cognitive dysfunction.

- Regular Follow-up and Adjustment: Continuous follow-up with both subjective patient feedback and objective cognitive assessments will ensure that any emerging deficits are quickly managed. Clinicians should be proactive in making dose adjustments or modifying treatment plans as needed to maintain optimal cognitive functioning.

Conclusions and Future Research

Summary of Findings

The overarching question of whether taking anti-depressants and anti-anxiety drugs can lower your intelligence is best addressed by understanding the complexity of cognitive functions and their modulation by pharmacotherapy. The following points summarize the insights from various perspectives:

- Multifactorial Nature of Cognition: Intelligence is derived from an interplay of multiple cognitive domains—including memory, executive function, attention, and processing speed—which can be transiently influenced by medications without constituting an overall decline in intellectual capacity.

- Transient vs. Permanent Effects: Clinical evidence suggests that while some anti-depressants and anti-anxiety drugs (especially those with sedative or anticholinergic properties) can produce short-term impairments in attention, processing speed, and memory, these effects are generally reversible and do not imply a permanent lowering of intelligence.

- Potential for Cognitive Improvement: In patients suffering from depression or anxiety, treatment often leads to an improvement in cognitive function as the underlying psychiatric symptoms are alleviated. This relief can result in better cognitive performance overall, counterbalancing any minor drug-induced impairments.

- Individual Variability and Dose Dependency: The degree of cognitive impact is variable and highly dependent on the specific medication, dosage, individual patient physiology, and the presence of underlying cognitive deficits. Careful management, monitoring, and adjustment of treatment regimens mitigate potential adverse effects.

- Management Strategies are Effective: Clinical strategies including personalized dosing, cognitive remediation therapies, regular neuropsychological assessments, and patient education have been shown to effectively manage any cognitive side effects, ensuring that long-term intelligence is not compromised.

Areas for Further Study

While current evidence overwhelmingly suggests that anti-depressants and anti-anxiety drugs do not permanently lower intelligence, several areas warrant further research:

- Longitudinal Studies in Diverse Populations: More long-term studies with diverse patient populations are needed to conclusively determine the chronic effects of these medications on overall cognitive function and to assess whether any subgroups may be at increased risk of persistent cognitive deficits.

- Mechanistic Research on Neuroplasticity: Further investigations into the molecular and cellular mechanisms, particularly the role of neuroplasticity and neurogenesis in response to pharmacotherapy, will help elucidate how these drugs contribute to cognitive improvements as well as transient impairments.

- Comparative Effectiveness Studies: Direct comparisons between different classes of anti-depressants and anti-anxiety drugs in terms of cognitive side effects could help guide clinicians in selecting medications with the most favorable cognitive profiles.

- Exploration of Combination Therapies: Research into the combined effects of pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions on cognitive outcomes can pave the way for more comprehensive treatment plans, especially for those prone to cognitive side effects.

- Impact on Specific Cognitive Domains: Detailed neuropsychological assessments that isolate effects on various components of intelligence (e.g., verbal memory, executive function, attention) will provide clearer insights into the cognitive fingerprint of these medications.

- Patient-Centered Outcomes: Future studies should incorporate patient-reported outcomes regarding subjective cognitive changes, as well as objective clinical measures, to bridge the gap between laboratory findings and real-world functional status.

In conclusion, while some anti-depressants and anti-anxiety medications—particularly those with sedative or anticholinergic properties—can lead to temporary cognitive impairments in certain domains, the current body of evidence does not support the notion that these drugs permanently lower intelligence. For most patients, the benefits of symptom relief and improved mood far outweigh any transient cognitive drawbacks, and targeted management strategies further minimize these effects. Future research aimed at refining our understanding of the drug-induced modulation of cognitive processes will be instrumental in optimizing treatment regimens and ensuring that patients receive both effective psychiatric care and the preservation of cognitive integrity.

By adopting a general-specific-general analytical approach, we appreciate that the impact of these medications on cognitive function is complex and multifactorial. At a broad level, anti-depressants and anti-anxiety drugs serve a critical role in mitigating psychiatric symptoms. In specific terms, while some cognitive side effects are observed, they are typically transient, dosage-dependent, and manageable. Generalizing these findings, there is no conclusive evidence that these medications lead to a permanent lowering of intelligence, particularly when treatment is carefully tailored and monitored. As research progresses, further refinements in pharmacotherapy and adjunctive cognitive interventions are expected to ensure optimal cognitive as well as emotional outcomes for patients.

Ultimately, based on the available synapse-supported references, taking anti-depressants and anti-anxiety drugs does not equate to permanently lowering one’s intelligence. Instead, these medications may transiently affect certain cognitive processes; however, proper management, individualized treatment plans, and the overall beneficial effects on mood and anxiety contribute to improved cognitive function in the long run rather than impairing overall intellectual capacity. Continued research and systematic assessments are essential to further inform both clinicians and patients, thereby optimizing treatment strategies that safeguard cognitive health while addressing psychiatric disorders.

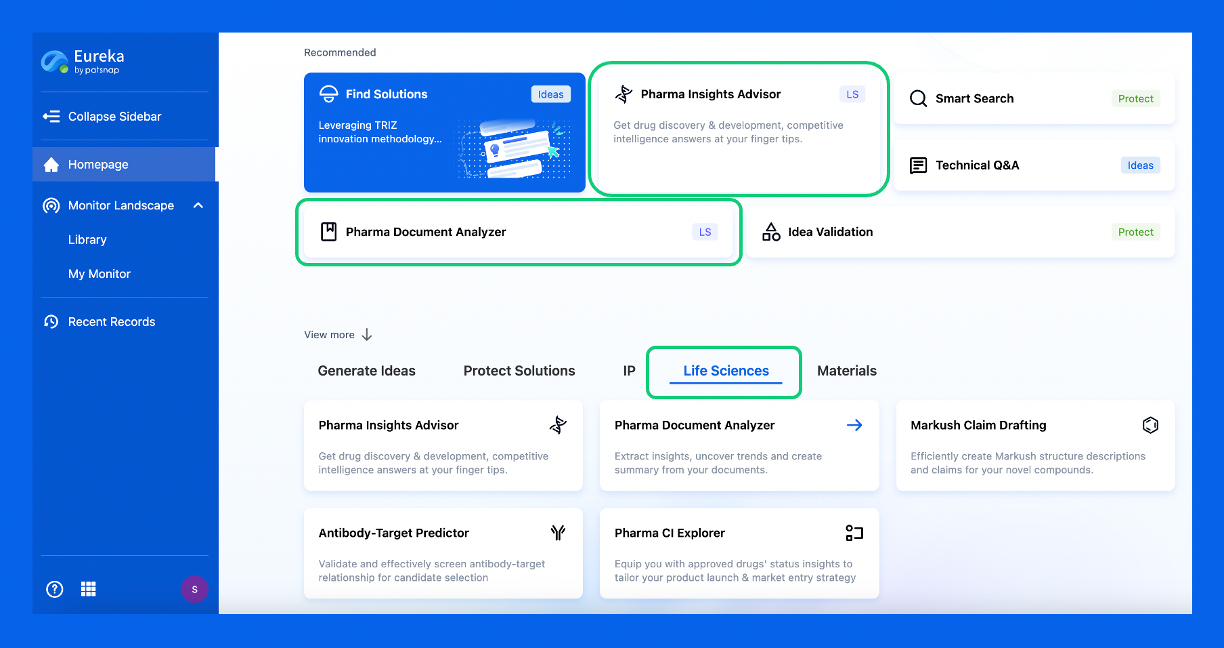

Discover Eureka LS: AI Agents Built for Biopharma Efficiency

Stop wasting time on biopharma busywork. Meet Eureka LS - your AI agent squad for drug discovery.

▶ See how 50+ research teams saved 300+ hours/month

From reducing screening time to simplifying Markush drafting, our AI Agents are ready to deliver immediate value. Explore Eureka LS today and unlock powerful capabilities that help you innovate with confidence.

AI Agents Built for Biopharma Breakthroughs

Accelerate discovery. Empower decisions. Transform outcomes.

Get started for free today!

Accelerate Strategic R&D decision making with Synapse, PatSnap’s AI-powered Connected Innovation Intelligence Platform Built for Life Sciences Professionals.

Start your data trial now!

Synapse data is also accessible to external entities via APIs or data packages. Empower better decisions with the latest in pharmaceutical intelligence.