Request Demo

Last update 28 Jun 2025

Amcenestrant

Last update 28 Jun 2025

Overview

Basic Info

Drug Type Small molecule drug |

Synonyms SAR 439859, SAR-439859, SAR439859 + [1] |

Target |

Action degraders |

Mechanism ERs degraders(Estrogen receptors degraders) |

Therapeutic Areas |

Active Indication- |

Inactive Indication |

Originator Organization |

Active Organization- |

Inactive Organization |

License Organization- |

Drug Highest PhaseDiscontinuedPhase 3 |

First Approval Date- |

Regulation- |

Login to view timeline

Structure/Sequence

Molecular FormulaC31H30Cl2FNO3 |

InChIKeyKISZAGQTIXIVAR-VWLOTQADSA-N |

CAS Registry2114339-57-8 |

Related

9

Clinical Trials associated with AmcenestrantNCT05128773

A Randomized, Multicenter, Double-blind, Phase 3 Study of Amcenestrant (SAR439859) Versus Tamoxifen for the Treatment of Patients With Hormone Receptor-positive, Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2-negative or Positive, Stage IIB-III Breast Cancer Who Have Discontinued Adjuvant Aromatase Inhibitor Therapy Due to Treatment-related Toxicity

This was a phase III, randomized, double blind, multicenter, 2-arm study evaluating the efficacy and safety of amcenestrant compared with tamoxifen in participants with hormone receptor-positive early breast cancer who discontinued adjuvant aromatase inhibitor (AI) therapy due to treatment related toxicity. The primary objective was to demonstrate the superiority of amcenestrant versus tamoxifen on invasive breast cancer-free survival.

The treatment duration per participant was to be 5 years, followed with a subsequent 5-years follow-up period. For the treatment period, visits were scheduled at the start of treatment, then at 4 weeks and 12 weeks after treatment start, and then every 12 weeks for the first 2 years and every 24 weeks for year 3 to 5. For the follow-up period, visits were scheduled 30 days after last treatment and then every 12 months. Three periods were planned:

* A screening period of up to 28 days,

* A treatment period of up to 5 years,

* A follow-up period of up to 5 years.

The treatment duration per participant was to be 5 years, followed with a subsequent 5-years follow-up period. For the treatment period, visits were scheduled at the start of treatment, then at 4 weeks and 12 weeks after treatment start, and then every 12 weeks for the first 2 years and every 24 weeks for year 3 to 5. For the follow-up period, visits were scheduled 30 days after last treatment and then every 12 months. Three periods were planned:

* A screening period of up to 28 days,

* A treatment period of up to 5 years,

* A follow-up period of up to 5 years.

Start Date17 Feb 2022 |

Sponsor / Collaborator  Sanofi Sanofi [+3] |

NCT05126329

An Open-label Pharmacokinetic and Tolerability Study of Amcenestrant Given as a Single Dose in Female Participants With Mild and Moderate Hepatic Impairment, and in Matched Participants With Normal Hepatic Function

This is a Phase 1, parallel, open-label, 3-arm study to investigate the pharmacokinetic (PK) parameters of amcenestrant in female participants aged 40 to 75 years with mild and moderate hepatic impairment, and in matched participants with normal hepatic function.

Start Date15 Nov 2021 |

Sponsor / Collaborator |

NCT04940026

A Phase 1, Open-label, Single Center, One Period, One Sequence Study to Determine Absorption, Metabolism, and Excretion of a Single Oral Dose of Radiolabeled [14C]- SAR439859 and an Assessment of the Absolute Oral Bioavailability Using the Microdosing Technique in Healthy Post-menopausal Women

Primary Objectives:

* To assess the excretion balance after oral and IV administration of [14C]-SAR439859

* To assess PK of total radioactivity, [14C] -SAR439859 and its metabolite (M7) after IV administration of [14C]-SAR439859 and, PK of radioactivity, SAR439859 and M7 after oral administration of SAR439859 alone or with [14C]-SAR439859

* To assess IV clearance and absolute bioavailability of SAR439859 using microdose of [14C]-SAR439859 tracer on top of a single tablet oral dose.

* To assess relative bioavailability of SAR439859 given as tablet or solution

Secondary objectives:

* To collect samples in order to assess metabolic profile in plasma and excreta of SAR439859 after oral administration of [14C]-SAR439859 as solution, contribution in plasma of SAR439859 and metabolite relative to total radioactivity and identify metabolites (samples will be analyzed according to metabolic analysis plan and results will be documented in a separate report).

* To assess safety and tolerance of SAR439859

* To assess the excretion balance after oral and IV administration of [14C]-SAR439859

* To assess PK of total radioactivity, [14C] -SAR439859 and its metabolite (M7) after IV administration of [14C]-SAR439859 and, PK of radioactivity, SAR439859 and M7 after oral administration of SAR439859 alone or with [14C]-SAR439859

* To assess IV clearance and absolute bioavailability of SAR439859 using microdose of [14C]-SAR439859 tracer on top of a single tablet oral dose.

* To assess relative bioavailability of SAR439859 given as tablet or solution

Secondary objectives:

* To collect samples in order to assess metabolic profile in plasma and excreta of SAR439859 after oral administration of [14C]-SAR439859 as solution, contribution in plasma of SAR439859 and metabolite relative to total radioactivity and identify metabolites (samples will be analyzed according to metabolic analysis plan and results will be documented in a separate report).

* To assess safety and tolerance of SAR439859

Start Date15 Jun 2021 |

Sponsor / Collaborator |

100 Clinical Results associated with Amcenestrant

Login to view more data

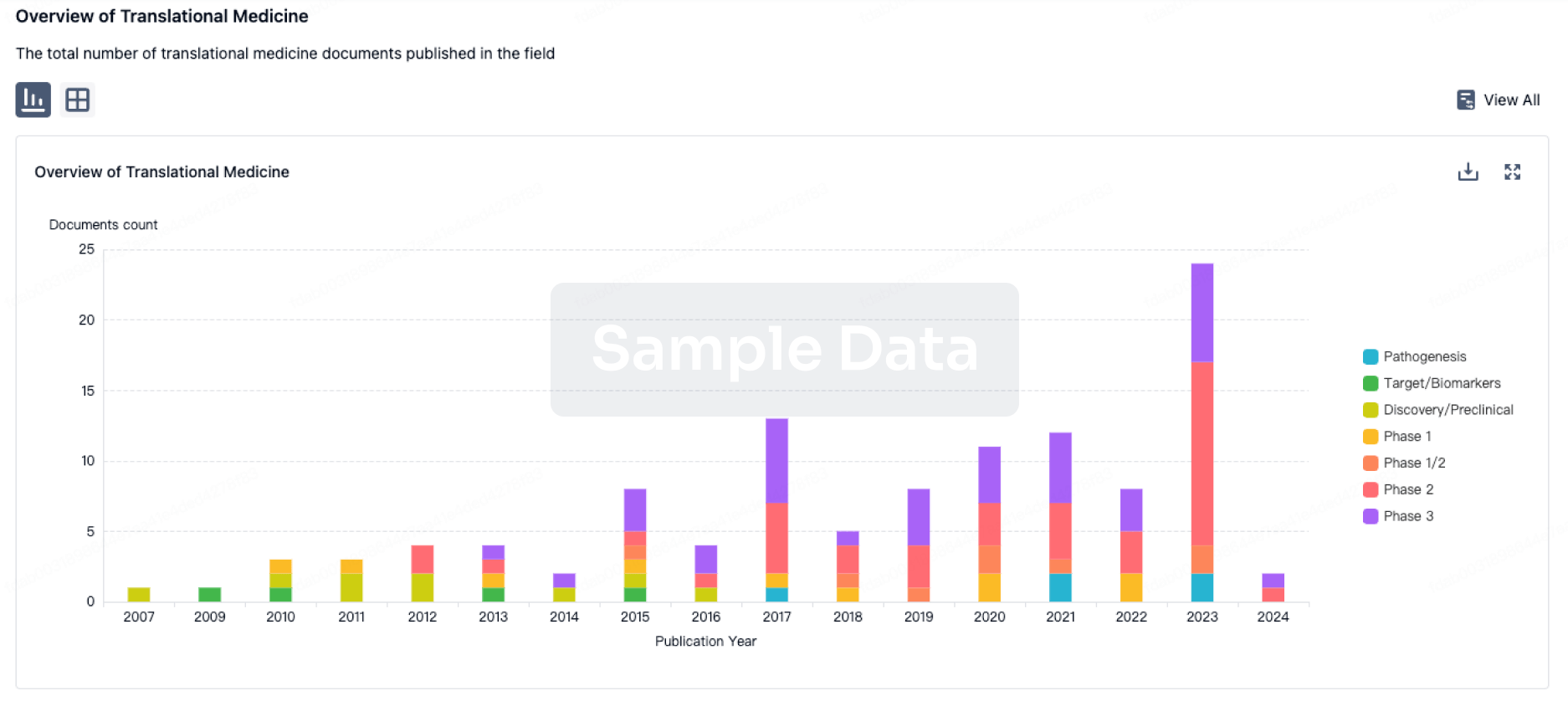

100 Translational Medicine associated with Amcenestrant

Login to view more data

100 Patents (Medical) associated with Amcenestrant

Login to view more data

31

Literatures (Medical) associated with Amcenestrant01 Apr 2025·TOXICOLOGICAL SCIENCES

Transcriptomic analysis in liver spheroids identifies a dog-specific mechanism of hepatotoxicity for amcenestrant

Article

Author: Dufault, Michael ; Laurent, Sébastien ; Adkins, Karissa ; Richards, Brenda ; Bajaj, Piyush ; Brennan, Richard J ; Sauzeat, Sylvie

Abstract:

Therapeutic drugs can sometimes cause adverse effects in a nonclinical species that do not translate to other species, including human. Species-specific (rat, dog, and human) in vitro liver spheroids were employed to understand the human relevance of cholestatic liver injury observed with a selective estrogen receptor degrader (amcenestrant) in dog, but not in rat, during preclinical development. Amcenestrant showed comparable cytotoxicity in liver spheroids from all 3 species; however, its M5 metabolite (RA15400562) showed dog preferential cytotoxicity after 7 days of treatment. Whole genome transcript profiles generated from liver spheroids revealed downregulation of genes related to bile acid synthesis and transport indicative of strong farnesoid X receptor (FXR) antagonism following treatment with both amcenestrant and its M5 metabolite in the dog but not in rat or human. In human spheroids, upregulation of genes for detoxification enzymes indicative of pregnane X receptor (PXR) agonism was observed following amcenestrant treatment, whereas in the dog these genes were downregulated. The M5 metabolite showed gene dysregulation indicating PXR agonism in both rat and human, and antagonism in dog. Analysis of liver samples from a 3-mo dog toxicity study conducted with amcenestrant showed downregulation of several genes associated with PXR and FXR, corroborating the in vitro results. These results support the hypothesis that dogs are uniquely susceptible to cholestatic hepatotoxicity following administration of amcenestrant due to species-specific antagonism of FXR and highlight the value of in vitro liver spheroids to investigating mechanisms of toxicity and possible species differences.

21 Mar 2025·ORGANIC LETTERS

Synthesis of Amcenestrant (SAR439859): A Copper-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reaction as a Sustainable Alternative to Palladium-Catalyzed Suzuki Reaction

Article

Author: Rodier, Fabien ; Ferey, Vincent ; Daumas, Marc ; Cruciani, Paul ; Bigot, Antony ; Cossy, Janine ; Nassar, Youssef

A cross-coupling reaction between an enol triflate and an aryl Grignard reagent using a copper catalyst, followed by a deprotection step, a Mitsunobu reaction, and a saponification, allowed for the synthesis of Amcenestrant (SAR439859). This approach, avoiding an expensive and toxic transition metal, is as efficient as the classical route but less expensive for accessing this selective estrogen-receptor degrader (SERD).

26 Feb 2025·ACS Central Science

Single Dose of a Small Molecule Leads to Complete Regressions of Large Breast Tumors in Mice

Article

Author: Fan, Timothy M. ; Shapiro, David J. ; Boudreau, Matthew W. ; Bouwens, Brooke A. ; Hergenrother, Paul J. ; Zhu, Junyao ; Carrell, Hunter W. ; Lee, Yoongyeong ; Nelson, Erik R. ; Mulligan, Michael P. ; Mousses, Spyro

Patients with estrogen receptor α positive (ERα+) breast cancer typically undergo surgical resection, followed by 5-10 years of treatment with adjuvant endocrine therapy. This prolonged intervention is associated with a host of undesired side effects that reduce patient compliance, and ultimately therapeutic resistance and disease relapse/progression are common. An ideal anticancer therapy would be effective against recurrent and refractory disease with minimal dosing; however, there is little precedent for marked tumor regression with a single dose of a small molecule therapeutic. Herein we report ErSO-TFPy as a small molecule that induces quantitative or near-quantitative regression of tumors in multiple mouse models of breast cancer with a single dose. Importantly, this effect is robust and independent of tumor size with eradication of even very large tumors (500-1500 mm3) observed. Mechanistically, these tumor regressions are a consequence of rapid induction of necrotic cell death in the tumor and are immune cell independent. If successfully translated to human cancer patients, the benefits of such an anticancer drug that is effective with a single dose would be significant.

29

News (Medical) associated with Amcenestrant31 May 2025

NEW HAVEN, CT and NEW YORK, NY, USA I May 31, 2025 I

Arvinas, Inc. (Nasdaq: ARVN) and Pfizer Inc. (NYSE: PFE) today announced detailed results from the Phase 3 VERITAC-2 clinical trial (NCT05654623) evaluating vepdegestrant monotherapy versus fulvestrant in adults with estrogen receptor-positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative (ER+/HER2-) advanced or metastatic breast cancer (MBC) whose disease progressed following prior treatment with cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) 4/6 inhibitors and endocrine therapy. These data, which were highlighted in the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO

®

) press briefing and selected for Best of ASCO, will be presented today in a late-breaking oral presentation (Abstract LBA1000) and have been simultaneously published in the

New England Journal of Medicine

.

In the trial, vepdegestrant demonstrated a statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvement in progression-free survival (PFS) among patients with an estrogen receptor 1 (ESR1) mutation, reducing the risk of disease progression or death by 43% compared to fulvestrant [Hazard Ratio (HR)=0.57 (95% CI 0.42–0.77); 2-sided P<0.001]. The median PFS, as assessed by blinded independent central review (BICR), was 5.0 months with vepdegestrant versus 2.1 months with fulvestrant. Investigator-assessed PFS was consistent with the BICR-assessed PFS. In patients with ESR1 mutations, vepdegestrant demonstrated a consistent PFS benefit over fulvestrant across all pre-specified subgroups. The trial did not reach statistical significance in improvement in PFS in the intent-to-treat (ITT) population, with a median PFS of 3.7 months for vepdegestrant versus 3.6 for fulvestrant [HR=0.83 (95% CI 0.68–1.02); 2-sided P=0.07].

“Many patients with ER+/HER2- metastatic breast cancer who progress on endocrine therapy have tumors with ESR1 mutations, which drive resistance to standard treatments,” said Erika P. Hamilton, M.D., Director, Breast Cancer Research, Sarah Cannon Research Institute, and a principal investigator of the VERITAC-2 trial. “The VERITAC-2 results are promising and suggest that vepdegestrant could offer a much-needed treatment option for these patients, with a low incidence of burdensome GI effects that can meaningfully affect daily life.”

Vepdegestrant was generally well tolerated in the trial, with a safety profile consistent with what has been observed in previous studies, and mostly low-grade treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs). Rates and severity of gastrointestinal adverse events were low with vepdegestrant (nausea, 13.5%; vomiting, 6.4%; diarrhea, 6.4%). Grade 4 TEAEs were reported in 5 patients (1.6%) in the vepdegestrant arm versus 9 patients (2.9%) in the fulvestrant arm. The three most common TEAEs observed with vepdegestrant were fatigue (26.6%), increased alanine transaminase (ALT) (14.4%) and increased aspartate aminotransferase (AST) (14.4%). TEAEs leading to treatment discontinuation occurred in 2.9% of patients taking vepdegestrant versus 0.7% of patients taking fulvestrant.

“Based on these strong data from VERITAC-2, we believe that vepdegestrant has the potential to be a best-in-class monotherapy treatment for patients in the second-line ESR1-mutant setting,” said John Houston, Ph.D., Chairperson, Chief Executive Officer and President at Arvinas. “We are excited to engage with regulatory authorities on next steps to potentially bring vepdegestrant to healthcare providers and their patients as swiftly as possible.”

Overall survival (OS), the key secondary endpoint in VERITAC-2, was immature at the time of the analysis, with less than a quarter of the required number of events having occurred. Additional secondary endpoints include clinical benefit rate (CBR) and objective response rate (ORR) and duration of response by BICR. In patients with an ESR1 mutation, CBR was 42.1% with vepdegestrant versus 20.2% with fulvestrant [odds ratio 2.88 (95% CI: 1.57–5.39); nominal P<0.001] and ORR was 18.6% with vepdegestrant versus 4.0% with fulvestrant [odds ratio 5.45 (95% CI: 1.69–22.73); nominal P=0.001]. The median duration of response was not reached.

“Patients whose tumors harbor ESR1 mutations can face a poor prognosis, often experiencing rapid disease progression on endocrine therapy,” said Johanna Bendell, M.D., Chief Oncology Development Officer, Pfizer. “These results highlight the important role vepdegestrant may play in combating ESR1 mutation treatment resistance for these patients.”

Approximately 2.3 million new breast cancer diagnoses were reported globally in 2022, and it is estimated there will be nearly 320,000 new diagnoses in the United States in 2025. ER+/HER2- breast cancer accounts for approximately 70% of all cases. Nearly 30% of women initially diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer will ultimately develop metastatic disease,

1

with resistance to current standard-of-care treatments often emerging during first-line therapy, leading to disease progression. ESR1 mutations are a common cause of acquired resistance and are found in approximately 40% of patients in the second-line setting.

2,3,4

Vepdegestrant, an investigational oral PROTAC ER degrader for ER+/HER2- breast cancer being jointly developed by Arvinas and Pfizer, is designed to harness the body’s natural protein disposal system to specifically target and degrade the ER. These detailed results follow the March 2025 announcement of the topline results from VERITAC-2. The companies plan to submit a New Drug Application (NDA) for vepdegestrant to the U.S. Food & Drug Administration (FDA) in the second half of 2025.

ASCO Presentation Details

“Vepdegestrant, a PROTAC Estrogen Receptor Degrader, vs Fulvestrant in ER-Positive/Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2-Negative Advanced Breast Cancer: Results of the Global, Randomized, Phase 3 VERITAC-2 Study” will be presented by Dr. Erika Hamilton, MD, Sarah Cannon Research Institute, in the Oral Abstract Session, Breast Cancer—Metastatic on Saturday, May 31, 1:15 – 4:15 p.m. CDT in Hall B1. Abstract LBA1000.

Investor Call and Webcast Details

Arvinas will host a conference call and webcast on June 2, 2025, at 8:00 a.m. ET to review these data. Participants are invited to listen by going to the Events and Presentation section under the Investors page on the Arvinas website at

www.arvinas.com

. A replay of the webcast will be available on the Arvinas website following the completion of the event and will be archived for up to 30 days.

About the VERITAC-2 Clinical Trial

The Phase 3 VERITAC-2 clinical trial (

NCT05654623

) is a global randomized trial evaluating the efficacy and safety of vepdegestrant (ARV-471) as a monotherapy compared to fulvestrant in patients with ER+/HER2- advanced or metastatic breast cancer. The trial enrolled 624 patients at sites in 26 countries who had previously received treatment with a CDK4/6 inhibitor plus endocrine therapy.

Patients were randomized 1:1 to receive either vepdegestrant once daily, orally on a 28-day continuous dosing schedule, or fulvestrant, administered intramuscularly on Days 1 and 15 of Cycle 1 and then on Day 1 of each 28-day cycle starting from Day 1 of Cycle 2. In the trial, 43% of patients (n=270) had ESR1 mutations detected. The primary endpoint was progression-free survival (PFS) in the ESR1-mutation and intent-to-treat populations as determined by blinded independent central review. Overall survival is the key secondary endpoint.

About Vepdegestrant

Vepdegestrant is an investigational, orally bioavailable PROteolysis TArgeting Chimera (PROTAC) protein degrader designed to specifically target and degrade the estrogen receptor (ER) for the treatment of patients with ER-positive (ER+)/human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-negative (ER+/HER2-) breast cancer. Vepdegestrant is being developed as a potential monotherapy for ER+/HER2- advanced or metastatic breast cancer with estrogen receptor 1 (ESR1) mutations in the second line-plus setting.

In July 2021, Arvinas announced a global collaboration with Pfizer for the co-development and co-commercialization of vepdegestrant; Arvinas and Pfizer will share worldwide development costs, commercialization expenses, and profits.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted vepdegestrant Fast Track designation as a monotherapy in the treatment of adults with ER+/HER2- advanced or metastatic breast cancer previously treated with endocrine-based therapy.

About Arvinas

Arvinas (Nasdaq: ARVN) is a clinical-stage biotechnology company dedicated to improving the lives of patients suffering from debilitating and life-threatening diseases. Through its PROTAC protein degrader platform, Arvinas is pioneering the development of protein degradation therapies designed to harness the body’s natural protein disposal system to selectively and efficiently degrade and remove disease-causing proteins. Arvinas is currently progressing multiple investigational drugs through clinical development programs, including vepdegestrant, targeting the estrogen receptor for patients with locally advanced or metastatic ER+/HER2- breast cancer; ARV-393, targeting BCL6 for relapsed/refractory non-Hodgkin Lymphoma; and ARV-102, targeting LRRK2 for neurodegenerative disorders. Arvinas is headquartered in New Haven, Connecticut. For more information about Arvinas, visit

www.arvinas.com

and connect on

LinkedIn

and

X

.

About Pfizer Oncology

At Pfizer Oncology, we are at the forefront of a new era in cancer care. Our industry-leading portfolio and extensive pipeline includes three core mechanisms of action to attack cancer from multiple angles, including small molecules, antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs), and bispecific antibodies, including other immune-oncology biologics. We are focused on delivering transformative therapies in some of the world’s most common cancers, including breast cancer, genitourinary cancer, hematology-oncology, and thoracic cancers, which includes lung cancer. Driven by science, we are committed to accelerating breakthroughs to help people with cancer live better and longer lives.

About Pfizer: Breakthroughs That Change Patients’ Lives

At Pfizer, we apply science and our global resources to bring therapies to people that extend and significantly improve their lives. We strive to set the standard for quality, safety and value in the discovery, development and manufacture of health care products, including innovative medicines and vaccines. Every day, Pfizer colleagues work across developed and emerging markets to advance wellness, prevention, treatments and cures that challenge the most feared diseases of our time. Consistent with our responsibility as one of the world’s premier innovative biopharmaceutical companies, we collaborate with health care providers, governments and local communities to support and expand access to reliable, affordable health care around the world. For 175 years, we have worked to make a difference for all who rely on us. We routinely post information that may be important to investors on our website at

www.pfizer.com

. In addition, to learn more, please visit us on

www.pfizer.com

and follow us on X at

@Pfizer

and

@Pfizer_News

,

LinkedIn

,

YouTube

and like us on Facebook at

Facebook.com/Pfizer

.

1

Redig AJ, McAllister SS. Breast cancer as a systemic disease: a view of metastasis.

J Intern Med

. 2013;274(2):113-126. doi:10.1111/joim.12084.

2

Bidard F-C, et al. Elacestrant (oral selective estrogen receptor degrader) Versus Standard Endocrine Therapy for Estrogen Receptor–Positive, Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2–Negative Advanced Breast Cancer: Results From the Randomized Phase III EMERALD Trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2022 May

https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.22.00338

.

3

Kalinsky, K. Abemaciclib Plus Fulvestrant in Advanced Breast Cancer After Progression on CDK4/6 Inhibition: Results From the Phase III postMONARCH Trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2024 Dec.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39693591/

.

4

Tolaney, S. et al. AMEERA-3: Randomized Phase II Study of Amcenestrant (Oral Selective Estrogen Receptor Degrader) Versus Standard Endocrine Monotherapy in Estrogen Receptor–Positive, Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2–Negative Advanced Breast Cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology.

https://ascopubs.org/doi/full/10.1200/JCO.22.02746

.

SOURCE:

Arvinas

Clinical ResultPhase 3ASCOPhase 2Fast Track

31 May 2025

Pivotal Phase 3 VERITAC-2 clinical trial results presented at ASCO demonstrate 2.9-month improvement in median progression-free survival when compared to fulvestrant in second line-plus patients with an estrogen receptor 1 mutation Vepdegestrant was generally well tolerated, with few discontinuations and low rates of gastrointestinal-related adverse events Vepdegestrant is the first and only PROteolysis TArgeting Chimera (PROTAC) evaluated in a Phase 3 clinical trial and the first to show benefit in patients with breast cancer Data to be featured in a late-breaking oral presentation at ASCO and simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine Arvinas will host a conference call to discuss these results on Monday, June 2, at 8:00 a.m. ET

NEW HAVEN, Conn. and NEW YORK, May 31, 2025 – Arvinas, Inc. (Nasdaq: ARVN) and Pfizer Inc. (NYSE: PFE) today announced detailed results from the Phase 3 VERITAC-2 clinical trial (NCT05654623) evaluating vepdegestrant monotherapy versus fulvestrant in adults with estrogen receptor-positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative (ER+/HER2-) advanced or metastatic breast cancer (MBC) whose disease progressed following prior treatment with cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) 4/6 inhibitors and endocrine therapy. These data, which were highlighted in the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO®) press briefing and selected for Best of ASCO, will be presented today in a late-breaking oral presentation (Abstract LBA1000) and have been simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

In the trial, vepdegestrant demonstrated a statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvement in progression-free survival (PFS) among patients with an estrogen receptor 1 (ESR1) mutation, reducing the risk of disease progression or death by 43% compared to fulvestrant [Hazard Ratio (HR)=0.57 (95% CI 0.42–0.77); 2-sided P<0.001]. The median PFS, as assessed by blinded independent central review (BICR), was 5.0 months with vepdegestrant versus 2.1 months with fulvestrant. Investigator-assessed PFS was consistent with the BICR-assessed PFS. In patients with ESR1 mutations, vepdegestrant demonstrated a consistent PFS benefit over fulvestrant across all pre-specified subgroups. The trial did not reach statistical significance in improvement in PFS in the intent-to-treat (ITT) population, with a median PFS of 3.7 months for vepdegestrant versus 3.6 for fulvestrant [HR=0.83 (95% CI 0.68–1.02); 2-sided P=0.07].

“Many patients with ER+/HER2- metastatic breast cancer who progress on endocrine therapy have tumors with ESR1 mutations, which drive resistance to standard treatments,” said Erika P. Hamilton, M.D., Director, Breast Cancer Research, Sarah Cannon Research Institute, and a principal investigator of the VERITAC-2 trial. “The VERITAC-2 results are promising and suggest that vepdegestrant could offer a much-needed treatment option for these patients, with a low incidence of burdensome GI effects that can meaningfully affect daily life.”

Vepdegestrant was generally well tolerated in the trial, with a safety profile consistent with what has been observed in previous studies, and mostly low-grade treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs). Rates and severity of gastrointestinal adverse events were low with vepdegestrant (nausea, 13.5%; vomiting, 6.4%; diarrhea, 6.4%). Grade 4 TEAEs were reported in 5 patients (1.6%) in the vepdegestrant arm versus 9 patients (2.9%) in the fulvestrant arm. The three most common TEAEs observed with vepdegestrant were fatigue (26.6%), increased alanine transaminase (ALT) (14.4%) and increased aspartate aminotransferase (AST) (14.4%). TEAEs leading to treatment discontinuation occurred in 2.9% of patients taking vepdegestrant versus 0.7% of patients taking fulvestrant.

“Based on these strong data from VERITAC-2, we believe that vepdegestrant has the potential to be a best-in-class monotherapy treatment for patients in the second-line ESR1-mutant setting,” said John Houston, Ph.D., Chairperson, Chief Executive Officer and President at Arvinas. “We are excited to engage with regulatory authorities on next steps to potentially bring vepdegestrant to healthcare providers and their patients as swiftly as possible.”

Overall survival (OS), the key secondary endpoint in VERITAC-2, was immature at the time of the analysis, with less than a quarter of the required number of events having occurred. Additional secondary endpoints include clinical benefit rate (CBR) and objective response rate (ORR) and duration of response by BICR. In patients with an ESR1 mutation, CBR was 42.1% with vepdegestrant versus 20.2% with fulvestrant [odds ratio 2.88 (95% CI: 1.57–5.39); nominal P<0.001] and ORR was 18.6% with vepdegestrant versus 4.0% with fulvestrant [odds ratio 5.45 (95% CI: 1.69–22.73); nominal P=0.001]. The median duration of response was not reached.

“Patients whose tumors harbor ESR1 mutations can face a poor prognosis, often experiencing rapid disease progression on endocrine therapy,” said Johanna Bendell, M.D., Chief Oncology Development Officer, Pfizer. “These results highlight the important role vepdegestrant may play in combating ESR1 mutation treatment resistance for these patients.”

Approximately 2.3 million new breast cancer diagnoses were reported globally in 2022, and it is estimated there will be nearly 320,000 new diagnoses in the United States in 2025. ER+/HER2- breast cancer accounts for approximately 70% of all cases. Nearly 30% of women initially diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer will ultimately develop metastatic disease,1 with resistance to current standard-of-care treatments often emerging during first-line therapy, leading to disease progression. ESR1 mutations are a common cause of acquired resistance and are found in approximately 40% of patients in the second-line setting.2,3,4

Vepdegestrant, an investigational oral PROTAC ER degrader for ER+/HER2- breast cancer being jointly developed by Arvinas and Pfizer, is designed to harness the body’s natural protein disposal system to specifically target and degrade the ER. These detailed results follow the March 2025 announcement of the topline results from VERITAC-2. The companies plan to submit a New Drug Application (NDA) for vepdegestrant to the U.S. Food & Drug Administration (FDA) in the second half of 2025.

ASCO Presentation Details

"Vepdegestrant, a PROTAC Estrogen Receptor Degrader, vs Fulvestrant in ER-Positive/Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2-Negative Advanced Breast Cancer: Results of the Global, Randomized, Phase 3 VERITAC-2 Study" will be presented by Dr. Erika Hamilton, MD, Sarah Cannon Research Institute, in the Oral Abstract Session, Breast Cancer—Metastatic on Saturday, May 31, 1:15 – 4:15 p.m. CDT in Hall B1. Abstract LBA1000.

Investor Call and Webcast Details

Arvinas will host a conference call and webcast on June 2, 2025, at 8:00 a.m. ET to review these data. Participants are invited to listen by going to the Events and Presentation section under the Investors page on the Arvinas website at www.arvinas.com. A replay of the webcast will be available on the Arvinas website following the completion of the event and will be archived for up to 30 days.

About the VERITAC-2 Clinical Trial

The Phase 3 VERITAC-2 clinical trial (NCT05654623) is a global randomized trial evaluating the efficacy and safety of vepdegestrant (ARV-471) as a monotherapy compared to fulvestrant in patients with ER+/HER2- advanced or metastatic breast cancer. The trial enrolled 624 patients at sites in 26 countries who had previously received treatment with a CDK4/6 inhibitor plus endocrine therapy.

Patients were randomized 1:1 to receive either vepdegestrant once daily, orally on a 28-day continuous dosing schedule, or fulvestrant, administered intramuscularly on Days 1 and 15 of Cycle 1 and then on Day 1 of each 28-day cycle starting from Day 1 of Cycle 2. In the trial, 43% of patients (n=270) had ESR1 mutations detected. The primary endpoint was progression-free survival (PFS) in the ESR1-mutation and intent-to-treat populations as determined by blinded independent central review. Overall survival is the key secondary endpoint.

About Vepdegestrant

Vepdegestrant is an investigational, orally bioavailable PROteolysis TArgeting Chimera (PROTAC) protein degrader designed to specifically target and degrade the estrogen receptor (ER) for the treatment of patients with ER-positive (ER+)/human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-negative (ER+/HER2-) breast cancer. Vepdegestrant is being developed as a potential monotherapy for ER+/HER2- advanced or metastatic breast cancer with estrogen receptor 1 (ESR1) mutations in the second line-plus setting.

In July 2021, Arvinas announced a global collaboration with Pfizer for the co-development and co-commercialization of vepdegestrant; Arvinas and Pfizer will share worldwide development costs, commercialization expenses, and profits.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted vepdegestrant Fast Track designation as a monotherapy in the treatment of adults with ER+/HER2- advanced or metastatic breast cancer previously treated with endocrine-based therapy.

About Arvinas

Arvinas (Nasdaq: ARVN) is a clinical-stage biotechnology company dedicated to improving the lives of patients suffering from debilitating and life-threatening diseases. Through its PROTAC protein degrader platform, Arvinas is pioneering the development of protein degradation therapies designed to harness the body’s natural protein disposal system to selectively and efficiently degrade and remove disease-causing proteins. Arvinas is currently progressing multiple investigational drugs through clinical development programs, including vepdegestrant, targeting the estrogen receptor for patients with locally advanced or metastatic ER+/HER2- breast cancer; ARV-393, targeting BCL6 for relapsed/refractory non-Hodgkin Lymphoma; and ARV-102, targeting LRRK2 for neurodegenerative disorders. Arvinas is headquartered in New Haven, Connecticut. For more information about Arvinas, visit www.arvinas.com and connect on LinkedIn and X.

About Pfizer Oncology

At Pfizer Oncology, we are at the forefront of a new era in cancer care. Our industry-leading portfolio and extensive pipeline includes three core mechanisms of action to attack cancer from multiple angles, including small molecules, antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs), and bispecific antibodies, including other immune-oncology biologics. We are focused on delivering transformative therapies in some of the world’s most common cancers, including breast cancer, genitourinary cancer, hematology-oncology, and thoracic cancers, which includes lung cancer. Driven by science, we are committed to accelerating breakthroughs to help people with cancer live better and longer lives.

About Pfizer: Breakthroughs That Change Patients’ Lives

At Pfizer, we apply science and our global resources to bring therapies to people that extend and significantly improve their lives. We strive to set the standard for quality, safety and value in the discovery, development and manufacture of health care products, including innovative medicines and vaccines. Every day, Pfizer colleagues work across developed and emerging markets to advance wellness, prevention, treatments and cures that challenge the most feared diseases of our time. Consistent with our responsibility as one of the world's premier innovative biopharmaceutical companies, we collaborate with health care providers, governments and local communities to support and expand access to reliable, affordable health care around the world. For 175 years, we have worked to make a difference for all who rely on us. We routinely post information that may be important to investors on our website at www.pfizer.com. In addition, to learn more, please visit us on www.pfizer.com and follow us on X at @Pfizer and @Pfizer_News, LinkedIn, YouTube and like us on Facebook at Facebook.com/Pfizer.

Arvinas Forward-Looking Statements

This press release contains forward-looking statements within the meaning of The Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995 that involve substantial risks and uncertainties, including statements regarding: vepdegestrant’s development as a potential monotherapy for patients with estrogen receptor positive (“ER+”), human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 negative (“HER2-”), metastatic breast cancer with estrogen receptor 1 (“ESR1”) mutations in the second-line plus setting; vepdegestrant’s potential as a treatment option for patients with a low incidence of burdensome gastrointestinal effects; vepdegestrant’s potential to be a best-in-class monotherapy treatment for patients with ER+/HER2- metastatic breast cancer in the second-line ESR1-mutant setting; and Arvinas’ and Pfizer’s plans to engage with regulatory authorities on next steps to potentially bring vepdegestrant to healthcare providers and patients, and the companies’ plans to submit a New Drug Application to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, and the timing thereof. All statements, other than statements of historical fact, contained in this press release, including statements regarding Arvinas’ strategy, future operations, future financial position, future revenues, projected costs, prospects, plans and objectives of management, are forward-looking statements. The words “anticipate,” “believe,” “estimate,” “expect,” “intend,” “may,” “plan,” “target,” “goal,” “potential,” “will,” “would,” “could,” “should,” “look forward,” “continue,” and similar expressions are intended to identify forward-looking statements, although not all forward-looking statements contain these identifying words. Arvinas may not actually achieve the plans, intentions or expectations disclosed in these forward-looking statements, and you should not place undue reliance on such forward-looking statements. Actual results or events could differ materially from the plans, intentions and expectations disclosed in the forward-looking statements Arvinas makes as a result of various risks and uncertainties, including but not limited to: whether Arvinas and Pfizer will successfully perform their respective obligations under the collaboration between Arvinas and Pfizer; whether Arvinas and Pfizer will be able to successfully conduct and complete clinical development for vepdegestrant as a monotherapy; whether Arvinas will be able to successfully conduct and complete development for its other product candidates, including ARV-393 and ARV-102; whether Arvinas and Pfizer, as appropriate, will be able to obtain marketing approval for and commercialize vepdegestrant and other product candidates on current timelines or at all; Arvinas’ ability to protect its intellectual property portfolio; Arvinas’ reliance on third parties; whether Arvinas will be able to raise capital when needed; whether Arvinas’ cash and cash equivalents will be sufficient to fund its foreseeable and unforeseeable operating expenses and capital expenditure requirements; and other important factors discussed in the “Risk Factors” section of Arvinas’ Annual Report on Form 10-K for the year ended December 31, 2024 and subsequent other reports on file with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. The forward-looking statements contained in this press release reflect Arvinas’ current views with respect to future events, and Arvinas assumes no obligation to update any forward-looking statements, except as required by applicable law. These forward-looking statements should not be relied upon as representing Arvinas’ views as of any date subsequent to the date of this release.

Pfizer Disclosure Notice:

The information contained in this release is as of May 31, 2025. Pfizer assumes no obligation to update forward-looking statements contained in this release as the result of new information or future events or developments.

This release contains forward-looking information about Pfizer Oncology and vepdegestrant, including its potential benefits, detailed results from the Phase 3 VERITAC-2 clinical trial evaluating vepdegestrant monotherapy versus fulvestrant in adults with estrogen receptor-positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative (ER+/HER2-) advanced or metastatic breast cancer whose disease progressed following prior treatment with cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) 4/6 inhibitors and endocrine therapy and plans to submit a New Drug Application for vepdegestrant to the FDA in the second half of 2025 that involve substantial risks and uncertainties that could cause actual results to differ materially from those expressed or implied by such statements. Risks and uncertainties include, among other things, the uncertainties inherent in research and development, including the ability to meet anticipated clinical endpoints, commencement and/or completion dates for our clinical trials, regulatory submission dates, regulatory approval dates and/or launch dates, as well as the possibility of unfavorable new clinical data and further analyses of existing clinical data; whether the VERITAC-2 trial will meet the secondary endpoint for overall survival; the risk that clinical trial data are subject to differing interpretations and assessments by regulatory authorities; whether regulatory authorities will be satisfied with the design of and results from our clinical studies; whether and when drug applications may be filed in any jurisdictions for any potential indication for vepdegestrant; whether and when any such applications that may be filed for vepdegestrant may be approved by regulatory authorities, which will depend on myriad factors, including making a determination as to whether the product's benefits outweigh its known risks and determination of the product's efficacy, and, if approved, whether vepdegestrant will be commercially successful; decisions by regulatory authorities impacting labeling, manufacturing processes, safety and/or other matters that could affect the availability or commercial potential of vepdegestrant; whether the collaboration between Pfizer and Arvinas will be successful; risks and uncertainties related to issued or future executive orders or other new, or changes in, laws or regulations; uncertainties regarding the impact of COVID-19 on our business, operations and financial results; and competitive developments.

A further description of risks and uncertainties can be found in Pfizer’s Annual Report on Form 10-K for the fiscal year ended December 31, 2024, and in its subsequent reports on Form 10-Q, including in the sections thereof captioned “Risk Factors” and “Forward-Looking Information and Factors That May Affect Future Results”, as well as in its subsequent reports on Form 8-K, all of which are filed with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission and available at www.sec.gov

1 Redig AJ, McAllister SS. Breast cancer as a systemic disease: a view of metastasis. J Intern Med. 2013;274(2):113-126. doi:10.1111/joim.12084.2 Bidard F-C, et al. Elacestrant (oral selective estrogen receptor degrader) Versus Standard Endocrine Therapy for Estrogen Receptor–Positive, Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2–Negative Advanced Breast Cancer: Results From the Randomized Phase III EMERALD Trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2022 May https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.22.00338. 3 Kalinsky, K. Abemaciclib Plus Fulvestrant in Advanced Breast Cancer After Progression on CDK4/6 Inhibition: Results From the Phase III postMONARCH Trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2024 Dec. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO-24-0208.4 Tolaney, S. et al. AMEERA-3: Randomized Phase II Study of Amcenestrant (Oral Selective Estrogen Receptor Degrader) Versus Standard Endocrine Monotherapy in Estrogen Receptor–Positive, Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2–Negative Advanced Breast Cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. https://ascopubs.org/doi/full/10.1200/JCO.22.02746.

Pfizer Media Contact:

+1 (212) 733-1225

PfizerMediaRelations@Pfizer.com

Pfizer Investor Contact:

+1 (212) 733-4848

IR@Pfizer.com

Arvinas Media Contact:

Kirsten Owens

+1 (203) 584-0307

Kirsten.Owens@Arvinas.com

Arvinas Investor Contact:

Jeff Boyle

+1 (347) 247-5089

Jeff.Boyle@Arvinas.com

Clinical ResultPhase 3Fast TrackASCO

12 Mar 2025

– VERITAC-2 achieved its primary endpoint in the estrogen receptor 1-mutant population, demonstrating statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvement in progression-free survival –

– Vepdegestrant is the first PROTAC degrader to demonstrate clinical benefit

in a Phase 3 trial –

NEW HAVEN, CT and NEW YORK, NY, USA I March 11, 2025 I

Arvinas, Inc. (Nasdaq: ARVN) and Pfizer Inc. (NYSE: PFE) today announced positive topline results from the Phase 3 VERITAC-2 clinical trial (NCT05654623) evaluating vepdegestrant monotherapy versus fulvestrant in adults with estrogen receptor-positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative (ER+/HER2-) advanced or metastatic breast cancer whose disease progressed following prior treatment with cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) 4/6 inhibitors and endocrine therapy. These are the first pivotal data for vepdegestrant, a potential first-in-class investigational oral PROteolysis TArgeting Chimera (PROTAC) ER degrader.

The trial met its primary endpoint in the estrogen receptor 1-mutant (ESR1m) population, demonstrating a statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvement in progression-free survival (PFS) compared to fulvestrant. The results exceeded the pre-specified target hazard ratio of 0.60 in the ESR1m population. The trial did not reach statistical significance in improvement in PFS in the intent-to-treat (ITT) population.

“The first Phase 3 data readout for a PROTAC degrader represents a significant achievement and these data show that vepdegestrant has the potential to provide clinically meaningful outcomes for thousands of patients with metastatic breast cancer whose tumors harbor estrogen receptor 1 mutations,” said John Houston, Ph.D., Chairperson, Chief Executive Officer and President at Arvinas. “We want to thank the patients and investigators who participated in this trial, and we look forward to sharing these data with health authorities as well as at a medical conference in 2025.”

Overall survival was not mature at the time of the analysis, with less than a quarter of the required number of events having occurred. The trial will continue to assess overall survival as a key secondary endpoint. In the trial, vepdegestrant was generally well tolerated and its safety profile was consistent with what has been observed in previous studies. Detailed results from VERITAC-2 will be submitted for presentation at a medical meeting later this year, and these data will be shared with global regulatory authorities to potentially support regulatory filings.

“Patients with advanced ER+/HER2- metastatic breast cancer face significant clinical challenges, with limited treatment options following disease progression and the development of resistance to available endocrine therapies,” said Megan O’Meara, M.D., Interim Chief Development Officer, Pfizer Oncology. “These data from VERITAC-2 support the potential of vepdegestrant to give patients whose tumors harbor ESR1 mutations additional time without disease progression, compared to fulvestrant.”

Vepdegestrant is an investigational oral PROTAC ER degrader for ER+/HER2- breast cancer being jointly developed by Arvinas and Pfizer and is designed to harness the body’s natural protein disposal system to specifically target and degrade the ER. In February 2024, the companies announced that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) granted Fast Track designation for the investigation of vepdegestrant for monotherapy in the treatment of adults with ER+/HER2- advanced or metastatic breast cancer previously treated with endocrine-based therapy.

About Metastatic Breast Cancer

About 2.3 million new breast cancer diagnoses were reported globally in 2022,

1

and it is estimated there will be nearly 320,000 people diagnosed with breast cancer in the U.S. in 2025.

2

Estrogen receptor-positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative (ER+/HER2-) breast cancer accounts for approximately 70% of all cases.

3

Nearly 30% of women initially diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer will ultimately develop metastatic breast cancer (MBC),

4

the most advanced stage in which the disease has spread beyond the breast to other parts of the body. Treatment advances have helped those with MBC better manage symptoms, slow tumor growth, and may allow them to live longer, but most patients ultimately develop resistance to current standard-of-care treatments in the first-line setting and experience disease progression. ESR1 mutations are a common cause of acquired resistance and are found in approximately 40% of patients in the second-line setting.

5

6

7

About the VERITAC-2 Clinical Trial

The Phase 3 VERITAC-2 clinical trial (

NCT05654623

) is a global randomized study evaluating the efficacy and safety of vepdegestrant (ARV-471) as a monotherapy compared to fulvestrant in patients with ER+/HER2- advanced or metastatic breast cancer. The trial enrolled 624 patients at sites in 26 countries who had previously received treatment with a CDK4/6 inhibitor plus endocrine therapy.

Patients were randomized to receive either vepdegestrant once daily, orally on a 28-day continuous dosing schedule, or fulvestrant, administered intramuscularly on Days 1 and 15 of Cycle 1 and then on Day 1 of each 28-day cycle starting from Day 1 of Cycle 2. The primary endpoint was progression-free survival (PFS) in the intent-to-treat and ESR1m populations as determined by blinded independent central review. Overall survival is a key secondary endpoint.

About Vepdegestrant

Vepdegestrant is an investigational, orally bioavailable PROTAC (PROteolysis TArgeting Chimera) protein degrader designed to specifically target and degrade the estrogen receptor (ER) for the treatment of patients with ER-positive (ER+)/human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-negative (ER+/HER2-) breast cancer. Vepdegestrant is being developed as a potential monotherapy and as part of combination therapy across multiple treatment settings for ER+/HER2- metastatic breast cancer.

In July 2021, Arvinas announced a global collaboration with Pfizer for the co-development and co-commercialization of vepdegestrant; Arvinas and Pfizer will share worldwide development costs, commercialization expenses, and profits.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted vepdegestrant Fast Track designation as a monotherapy in the treatment of adults with ER+/HER2- advanced or metastatic breast cancer previously treated with endocrine-based therapy.

About Arvinas

Arvinas (Nasdaq: ARVN) is a clinical-stage biotechnology company dedicated to improving the lives of patients suffering from debilitating and life-threatening diseases. Through its PROTAC (PROteolysis TArgeting Chimera) protein degrader platform, the Company is pioneering the development of protein degradation therapies designed to harness the body’s natural protein disposal system to selectively and efficiently degrade and remove disease-causing proteins. Arvinas is currently progressing multiple investigational drugs through clinical development programs, including vepdegestrant, targeting the estrogen receptor for patients with locally advanced or metastatic ER+/HER2- breast cancer; ARV-393, targeting BCL6 for relapsed/refractory non-Hodgkin Lymphoma; and ARV-102, targeting LRRK2 for neurodegenerative disorders. Arvinas is headquartered in New Haven, Connecticut. For more information about Arvinas, visit

www.arvinas.com

and connect on

LinkedIn

and

X

.

About Pfizer Oncology

At Pfizer Oncology, we are at the forefront of a new era in cancer care. Our industry-leading portfolio and extensive pipeline includes three core mechanisms of action to attack cancer from multiple angles, including small molecules, antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs), and bispecific antibodies, including other immune-oncology biologics. We are focused on delivering transformative therapies in some of the world’s most common cancers, including breast cancer, genitourinary cancer, hematology-oncology, and thoracic cancers, which includes lung cancer. Driven by science, we are committed to accelerating breakthroughs to help people with cancer live better and longer lives.

About Pfizer: Breakthroughs That Change Patients’ Lives

At Pfizer, we apply science and our global resources to bring therapies to people that extend and significantly improve their lives. We strive to set the standard for quality, safety and value in the discovery, development and manufacture of health care products, including innovative medicines and vaccines. Every day, Pfizer colleagues work across developed and emerging markets to advance wellness, prevention, treatments and cures that challenge the most feared diseases of our time. Consistent with our responsibility as one of the world’s premier innovative biopharmaceutical companies, we collaborate with health care providers, governments and local communities to support and expand access to reliable, affordable health care around the world. For 175 years, we have worked to make a difference for all who rely on us. We routinely post information that may be important to investors on our website at

www.pfizer.com

. In addition, to learn more, please visit us on

www.pfizer.com

and follow us on X at

@Pfizer

and

@Pfizer_News

,

LinkedIn

,

YouTube

and like us on Facebook at

Facebook.com/Pfizer

.

1

World Health Organization. (2024, March 13).

Breast cancer

. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/breast-cancer

2

Siegel RL, Kratzer TB, Giaquinto AN, Sung H, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2025. CA Cancer J Clin. 2025 Jan-Feb;75(1):10-45. doi: 10.3322/caac.21871. Epub 2025 Jan 16. PMID: 39817679; PMCID: PMC11745215.

3

Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program Data,

https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/breast-subtypes.html

.

4

Redig AJ, McAllister SS. Breast cancer as a systemic disease: a view of metastasis.

J Intern Med

. 2013;274(2):113-126. doi:10.1111/joim.12084.

5

Bidard F-C, et al. Elacestrant (oral selective estrogen receptor degrader) Versus Standard Endocrine Therapy for Estrogen Receptor–Positive, Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2–Negative Advanced Breast Cancer: Results From the Randomized Phase III EMERALD Trial. Journal of Clinical Onoclogy. 2022 May

https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.22.00338

.

6

Kalinsky, K. Abemaciclib Plus Fulvestrant in Advanced Breast Cancer After Progression on CDK4/6 Inhibition: Results From the Phase III postMONARCH Trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2024 Dec.

https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO-24-0208

.

7

Tolaney, S. et al. AMEERA-3: Randomized Phase II Study of Amcenestrant (Oral Selective Estrogen Receptor Degrader) Versus Standard Endocrine Monotherapy in Estrogen Receptor–Positive, Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2–Negative Advanced Breast Cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology.

https://ascopubs.org/doi/full/10.1200/JCO.22.02746

.

SOURCE:

Arvinas

Clinical ResultPhase 3Fast TrackASCOPhase 2

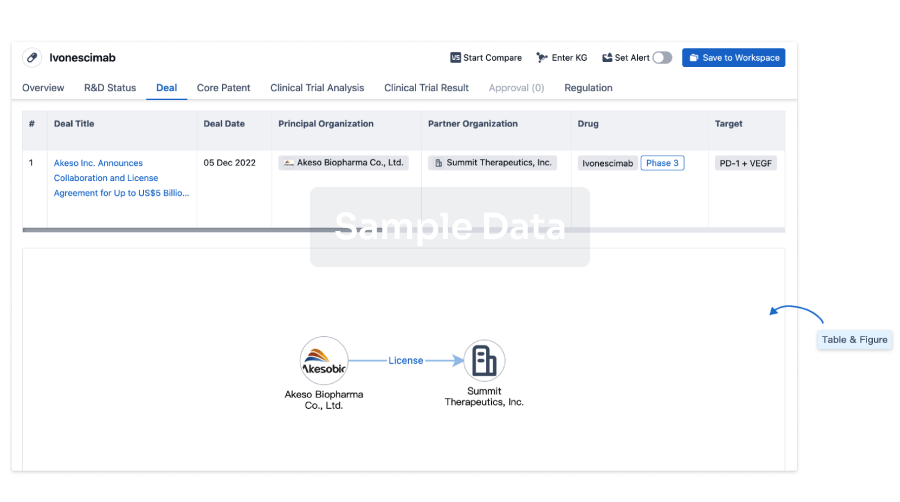

100 Deals associated with Amcenestrant

Login to view more data

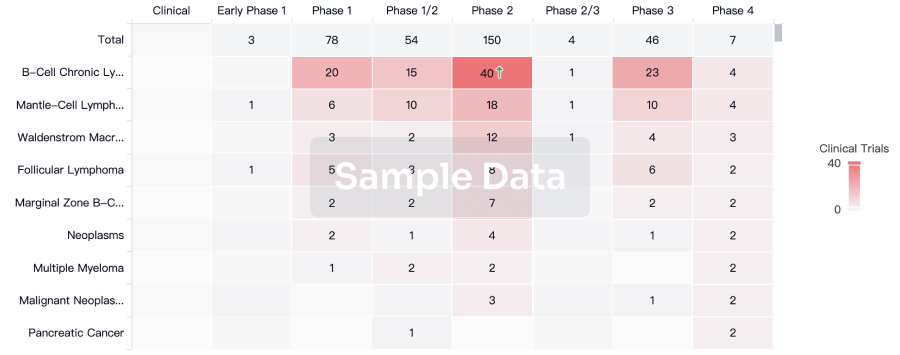

R&D Status

10 top R&D records. to view more data

Login

| Indication | Highest Phase | Country/Location | Organization | Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hormone receptor positive breast cancer | Phase 3 | China | 17 Feb 2022 | |

| Hormone receptor positive breast cancer | Phase 3 | Chile | 17 Feb 2022 | |

| HR Positive/HER2 Negative Lobular Carcinoma | Phase 3 | China | 17 Feb 2022 | |

| HR Positive/HER2 Negative Lobular Carcinoma | Phase 3 | Chile | 17 Feb 2022 | |

| Breast Cancer | Phase 3 | United States | 19 Nov 2020 | |

| Breast Cancer | Phase 3 | Japan | 19 Nov 2020 | |

| Breast Cancer | Phase 3 | Argentina | 19 Nov 2020 | |

| Breast Cancer | Phase 3 | Australia | 19 Nov 2020 | |

| Breast Cancer | Phase 3 | Austria | 19 Nov 2020 | |

| Breast Cancer | Phase 3 | Belgium | 19 Nov 2020 |

Login to view more data

Clinical Result

Clinical Result

Indication

Phase

Evaluation

View All Results

| Study | Phase | Population | Analyzed Enrollment | Group | Results | Evaluation | Publication Date |

|---|

Phase 3 | 1,068 | qbkoypwdra(jfqzlssagd) = rduegrokkx qsxtnqurcv (ffjllvbqle, 79.0 - 85.8) View more | Negative | 18 Jun 2024 | |||

qbkoypwdra(jfqzlssagd) = qfehjrempx qsxtnqurcv (ffjllvbqle, 83.5 - 89.6) View more | |||||||

NCT01042379 (ASCO2024) Manual | Phase 2 | Hormone receptor positive HER2 negative breast cancer Neoadjuvant HER2 Negative | Hormone Receptor Positive | 74 | Amcenestrant 200 mg qd | xknfyjgjph(fgyfjjzkkd) = Treatment in all 3 arms was feasible with 95% of pts completing >75% study therapy. gppcfqyeth (zjmhfwtlcb ) View more | Positive | 24 May 2024 |

Phase 3 | 1,068 | (Letrozole + Palbociclib) | ivgmiguvoo(mdsyrpgdca) = guwskauukk zsitaguguy (rijewowqvb, wuhvbvawrq - xijvshnwth) View more | - | 06 Jul 2023 | ||

(Amcenestrant + Palbociclib) | ivgmiguvoo(mdsyrpgdca) = rrraukocic zsitaguguy (rijewowqvb, vkgcohvozx - rqxnyeuzfy) View more | ||||||

Phase 3 | 3 | sztkrvcdbg(usoruvlttz) = reffakhjpn bjwbymlqrw (tnupthtevt, jdrbqkhmhp - hirwzcsdfs) View more | - | 22 Jun 2023 | |||

Phase 2 | 367 | xflqzlzasq(esaesllrqs) = tamcnycphy stmyxztqek (pxupudaavj, mkhfxorzsc - ucjzikzhhc) View more | - | 30 Mar 2023 | |||

Phase 2 | ER-positive/HER2-negative Breast Cancer ER Positive | HER2 Negative | 290 | Amcenestrantc 400 mg | vhubymaevo(vvfyajijaz) = cbomkdxuwr asnyizpjhy (dysiimstfc ) | Similar | 10 Sep 2022 | |

endocrine treatment of physician’s choice | vhubymaevo(vvfyajijaz) = fezgiwmpjt asnyizpjhy (dysiimstfc ) | ||||||

Phase 3 | 1,068 | qghozjowgx(puqjhdbtup) = amcenestrant in combination with palbociclib did not meet the prespecified boundary for continuation in comparison with the control arm and recommended stopping the trial. twzfpoasej (wrvatgaogb ) View more | Negative | 17 Aug 2022 | |||

Phase 1/2 | ER-positive/HER2-negative Breast Cancer ER-positive | HER2-negative | 65 | cuhkhnvkwj(lkgaxzdioe) = qhbqerfdjc mntiultxyb (thyjgdvjfu ) View more | Positive | 15 Jul 2022 | ||

Phase 2 | 105 | kycescgxol(cejaxtoplq) = No Grade ≥ 3 TRAEs occurred in any treatment arm vzwlnewwdq (nlgttpzequ ) View more | - | 02 Jun 2022 | |||

Phase 1/2 | ER-positive/HER2-negative Breast Cancer ER+ | HER2- | 39 | pwhedwmtrc(hpdqnwitxi) = Fatigue 7 (17.9%), Nausea 7 (17.9%), Arthralgia 4 (10.3%), Asthenia 4 (10.3%), Hot flush 4 (10.3%) hzvjcrjlyt (jaztaxlynu ) View more | Positive | 15 Feb 2022 |

Login to view more data

Translational Medicine

Boost your research with our translational medicine data.

login

or

Deal

Boost your decision using our deal data.

login

or

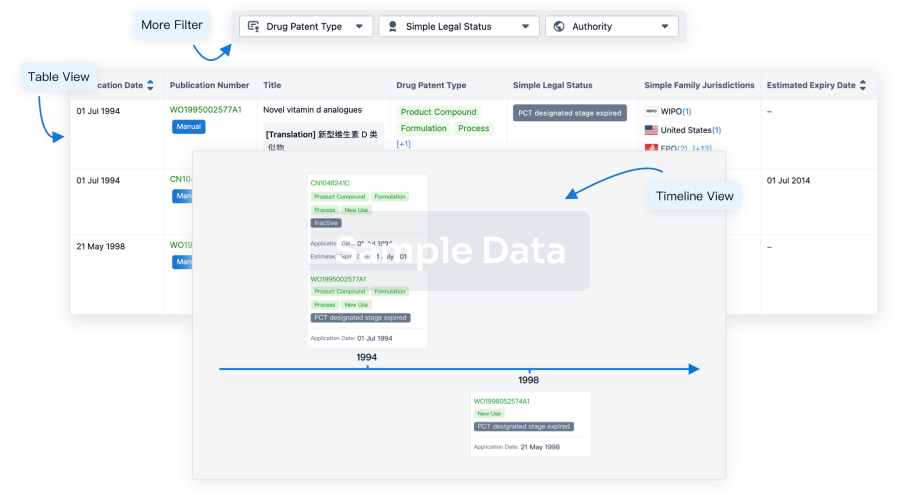

Core Patent

Boost your research with our Core Patent data.

login

or

Clinical Trial

Identify the latest clinical trials across global registries.

login

or

Approval

Accelerate your research with the latest regulatory approval information.

login

or

Regulation

Understand key drug designations in just a few clicks with Synapse.

login

or

AI Agents Built for Biopharma Breakthroughs

Accelerate discovery. Empower decisions. Transform outcomes.

Get started for free today!

Accelerate Strategic R&D decision making with Synapse, PatSnap’s AI-powered Connected Innovation Intelligence Platform Built for Life Sciences Professionals.

Start your data trial now!

Synapse data is also accessible to external entities via APIs or data packages. Empower better decisions with the latest in pharmaceutical intelligence.

Bio

Bio Sequences Search & Analysis

Sign up for free

Chemical

Chemical Structures Search & Analysis

Sign up for free