Request Demo

Last update 27 Feb 2026

Fenebrutinib

Last update 27 Feb 2026

Overview

Basic Info

Drug Type Small molecule drug |

Synonyms Fenebrutinib (USAN/INN), G-0853, GDC-0853 + [4] |

Target |

Action inhibitors |

Mechanism BTK C481S inhibitors(Bruton Tyrosine Kinase C481S inhibitors) |

Therapeutic Areas |

Active Indication |

Inactive Indication |

Originator Organization |

Active Organization |

Inactive Organization |

License Organization- |

Drug Highest PhasePhase 3 |

First Approval Date- |

Regulation- |

Login to view timeline

Structure/Sequence

Molecular FormulaC37H44N8O4 |

InChIKeyWNEODWDFDXWOLU-QHCPKHFHSA-N |

CAS Registry1434048-34-6 |

R&D Status

10 top R&D records. to view more data

Login

| Indication | Highest Phase | Country/Location | Organization | Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple sclerosis relapse | Phase 3 | Netherlands | - | 16 Nov 2020 |

| Rhabdomyosarcoma | Phase 3 | Netherlands | - | 16 Nov 2020 |

| Multiple Sclerosis, Primary Progressive | Phase 3 | United States | 26 Oct 2020 | |

| Multiple Sclerosis, Primary Progressive | Phase 3 | Argentina | 26 Oct 2020 | |

| Multiple Sclerosis, Primary Progressive | Phase 3 | Australia | 26 Oct 2020 | |

| Multiple Sclerosis, Primary Progressive | Phase 3 | Austria | 26 Oct 2020 | |

| Multiple Sclerosis, Primary Progressive | Phase 3 | Brazil | 26 Oct 2020 | |

| Multiple Sclerosis, Primary Progressive | Phase 3 | Bulgaria | 26 Oct 2020 | |

| Multiple Sclerosis, Primary Progressive | Phase 3 | Canada | 26 Oct 2020 | |

| Multiple Sclerosis, Primary Progressive | Phase 3 | Chile | 26 Oct 2020 |

Login to view more data

Clinical Result

Clinical Result

Indication

Phase

Evaluation

View All Results

Phase 3 | 1,497 | xwybbaxmnb(oxlqdvpbyg) = Fenebrutinib, an investigational Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor, significantly reduced the annualised relapse rate (ARR) compared to teriflunomide over a period of at least 96 weeks of treatment. rvlatatyhy (clpnivzhyd ) Met | Positive | 10 Nov 2025 | |||

Phase 3 | 985 | qrgrphvtxc(qxtrwaomxs) = The results showed that fenebrutinib was non-inferior compared to ocrelizumab, the only approved therapy in PPMS, as measured by a delay in the onset of composite confirmed disability progression over a period of at least 120 weeks of treatment. xhxostyjmn (elhnerniey ) Met | Non-inferior | 10 Nov 2025 | |||

Phase 2 | 99 | txcpsxieix(ncgfrruraw) = fyvsqiwjxn wxojsdiwat (aywmrfhfuz ) | Positive | 30 May 2025 | |||

Phase 2 | 99 | hiwtkrgcav(gxfofatqnz) = An asymptomatic alanine transaminase elevation occurred newly in one OLE participant (1%) that resolved gcignieiuv (audfcbakdc ) View more | Positive | 07 Apr 2025 | |||

Placebo | |||||||

Phase 2 | 109 | cgjxgkpsxq(rzmizbkypt) = yogaepoxcg waiqludqle (dcmxhfgftx ) View more | Positive | 04 Sep 2024 | |||

Phase 2 | 109 | (DBT Phase: Fenebrutinib) | mqksagqowc(vdwecxmiis) = odinmgodje ltpfyolkoj (pveqnehxyy, caxpwamxzr - yggybmykda) View more | - | 12 Jun 2024 | ||

placebo+fenebrutinib (DBT Phase: Placebo) | mqksagqowc(vdwecxmiis) = hormjvsbdp ltpfyolkoj (pveqnehxyy, wmxqdfvozc - wjppyfpwsw) View more | ||||||

Phase 1 | - | - | gxqnhcfpxb(pjgdtsbrdq) = Both doses were well tolerated, and no serious adverse events (AEs), AEs of special interest or Grade ≥2 AEs were reported pqsujsjsnv (vaphvyieiz ) | Positive | 09 Apr 2024 | ||

Phase 3 | - | giouxacyhr(mmvfwkoxvu) = ssakrmrxmj svmpvlhcau (rvsufmoopj ) | Negative | 05 Dec 2023 | |||

Phase 2 | 106 | Fenebrutinib 200 mg | qnemevrvhy(zkdlyzrgom) = hfdnoodmap lxacygwatj (zfmnqvrhta ) View more | Positive | 17 Oct 2023 | ||

Placebo | qnemevrvhy(zkdlyzrgom) = qygnyhmmie lxacygwatj (zfmnqvrhta ) View more | ||||||

Phase 2 | 260 | npkstwhbub(yyklkxibvj) = xkjrxsqwkx rjlcompjyx (nskdcybfci ) | - | 02 Jun 2021 |

Login to view more data

Translational Medicine

Boost your research with our translational medicine data.

login

or

Deal

Boost your decision using our deal data.

login

or

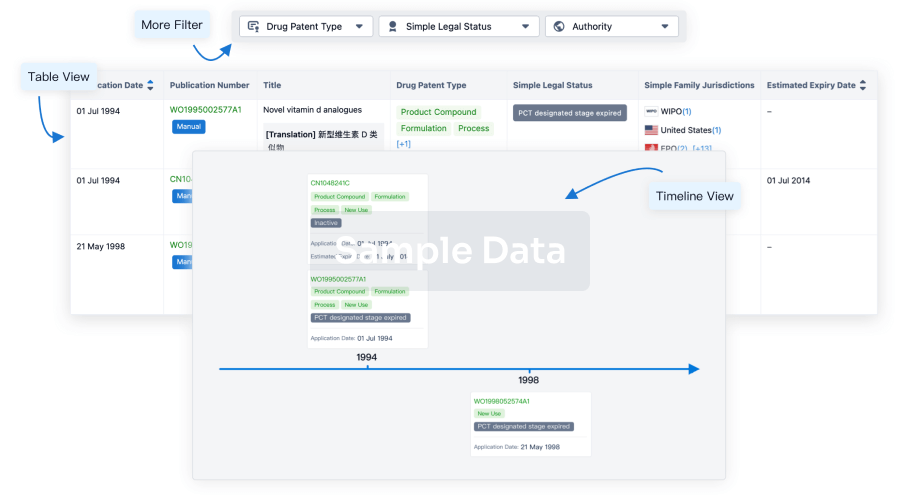

Core Patent

Boost your research with our Core Patent data.

login

or

Clinical Trial

Identify the latest clinical trials across global registries.

login

or

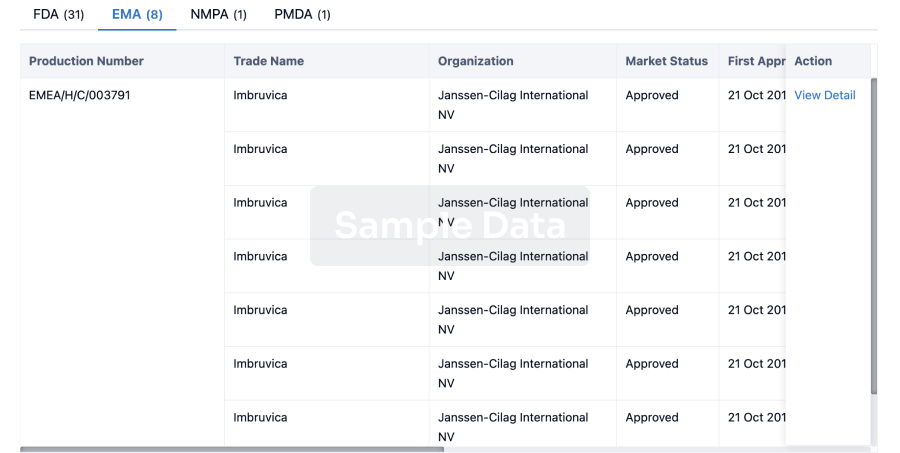

Approval

Accelerate your research with the latest regulatory approval information.

login

or

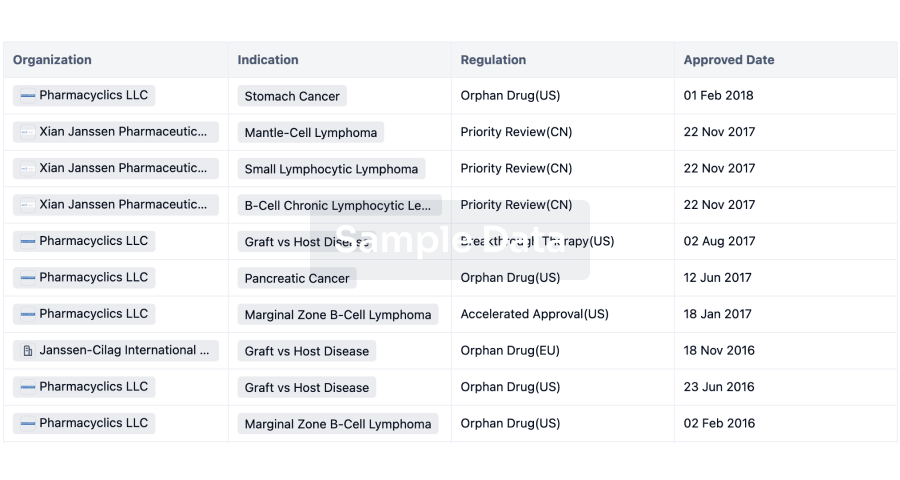

Regulation

Understand key drug designations in just a few clicks with Synapse.

login

or

AI Agents Built for Biopharma Breakthroughs

Accelerate discovery. Empower decisions. Transform outcomes.

Get started for free today!

Accelerate Strategic R&D decision making with Synapse, PatSnap’s AI-powered Connected Innovation Intelligence Platform Built for Life Sciences Professionals.

Start your data trial now!

Synapse data is also accessible to external entities via APIs or data packages. Empower better decisions with the latest in pharmaceutical intelligence.

Bio

Bio Sequences Search & Analysis

Sign up for free

Chemical

Chemical Structures Search & Analysis

Sign up for free