Request Demo

Last update 08 May 2025

Harbor Diversified, Inc.

Last update 08 May 2025

Overview

Related

8

Drugs associated with Harbor Diversified, Inc.Target |

Mechanism ERK inhibitors [+1] |

Active Org. |

Originator Org. |

Active Indication |

Inactive Indication |

Drug Highest PhasePhase 3 |

First Approval Ctry. / Loc.- |

First Approval Date- |

Target |

Mechanism NF-κB inhibitors |

Active Org.- |

Originator Org. |

Active Indication- |

Inactive Indication |

Drug Highest PhaseDiscontinued |

First Approval Ctry. / Loc.- |

First Approval Date- |

Target |

Mechanism AR antagonists |

Active Org.- |

Originator Org. |

Active Indication- |

Inactive Indication |

Drug Highest PhaseDiscontinued |

First Approval Ctry. / Loc.- |

First Approval Date- |

7

Clinical Trials associated with Harbor Diversified, Inc.NCT00991107

A Phase I, Open Label Study of the Safety, Tolerance and Assessment of HE3286 on Insulin Sensitivity and Hepatic Glucose Production When Administered Orally to Obese Insulin-Resistant Adult Subjects for 28 Days

The objectives of this study are to evaluate the safety and tolerance of 20 mg (10 mg BID) of HE3286 when administered orally over 28 days to obese insulin-resistant adult subjects and, to assess the activity of HE3286 on insulin sensitivity and hepatic glucose production in obese insulin-resistant adult subjects.

Start Date01 Sep 2009 |

Sponsor / Collaborator |

NCT00712114

A Phase I/II, Open Label, Dose Ranging Study of the Safety, Tolerance, Pharmacokinetics and Potential Anti-Inflammatory Activity of HE3286 When Administered Orally for 29 Days to Patients With Rheumatoid Arthritis on a Stable Dose of Methotrexate

The purpose of this pilot, exploratory study is to evaluate the safety, tolerance, pharmacokinetics and potential anti-inflammatory activity of an investigational agent, HE3286, when administered orally for 29 days to patients with rheumatoid arthritis that are taking a stable dose of methotrexate.

Start Date01 Jul 2008 |

Sponsor / Collaborator |

NCT00716794

A Phase I/II, Open-Label, Dose Ranging Study of the Safety, Tolerance, Pharmacokinetics and Potential Activity of HE3235 When Administered Orally to Patients With Prostate Cancer

This is a phase I/II, open-label, dose escalation study of HE3235 administered orally to patients with advanced prostate cancer who have failed hormone therapy and at least one taxane based chemotherapy regimen.

Start Date01 Jul 2008 |

Sponsor / Collaborator |

100 Clinical Results associated with Harbor Diversified, Inc.

Login to view more data

0 Patents (Medical) associated with Harbor Diversified, Inc.

Login to view more data

18

Literatures (Medical) associated with Harbor Diversified, Inc.11 Sep 2014·Investigative Opthalmology & Visual ScienceQ2 · MEDICINE

HE3286 Reduces Axonal Loss and Preserves Retinal Ganglion Cell Function in Experimental Optic Neuritis

Q2 · MEDICINE

ArticleOA

Author: Dine, Kimberly ; Shindler, Kenneth S. ; Luna, Esteban ; Khan, Reas S. ; Ahlem, Clarence

01 Jan 2013·Mediators of InflammationQ3 · MEDICINE

An Anti-Inflammatory Sterol Decreases Obesity-Related Inflammation-Induced Insulin Resistance and Metabolic Dysregulation

Q3 · MEDICINE

ArticleOA

Author: Reading, Chris L. ; Stickney, Dwight R. ; Frincke, James M. ; Flores-Riveros, Jaime

01 Jan 2013·BioMed Research InternationalQ3 · BIOLOGY

A New Parasiticidal Compound inT. soliumCysticercosis

Q3 · BIOLOGY

ArticleOA

Author: Reading, Chris ; Hernández-Bello, Romel ; Dowding, Charles ; Frincke, James ; Escobedo, Galileo ; Cervantes-Rebolledo, Claudia ; Carrero, Julio Cesar ; Morales-Montor, Jorge

3

News (Medical) associated with Harbor Diversified, Inc.19 Dec 2022

The total funding could reach €17.5 million ($18.6 million).

Paris-based Carmat develops a total artificial heart. It designed the platform to provide a therapeutic alternative for those suffering from end-stage biventricular heart failure.

EIC Accelerator funds European companies aiming to bring innovations to market. The council selected Carmat and its Aeson artificial heart, recognizing it as a “high-quality medical innovation,” according to a news release.

As a result of the selection, Carmat received the maximum possible funding available. It picked up a non-dilutive grant of €2.5 million ($2.7 million) to support the industrialization of Aeson. Additionally, Carmat received an optional equity financing of €15 million ($15.9 million). This funding, from the European Innovation Council Fund, supports marketing efforts for Aeson.

“We are proud and grateful to have been awarded within this prestigious program,” said Stéphane Piat, Carmat CEO. “The EIC’s decision confirms the very high quality and strong potential of our innovation and gives us access to substantial funding to support our development. I would like to thank all the Carmat teams involved in this challenging call for projects, which once again highlights the urgent need for an innovative solution to treat advanced biventricular heart failure.”

Carmat’s Aeson artificial heart system includes three parts: an implanted prosthesis, external equipment and a hospital care console. The prosthesis includes two micro pumps that push the actuator fluid to the membranes and generate the systole and diastole. There are two ventricles chambers, with a membrane separating them. One part is for blood, and one is for the actuator flood. The Aeson’s creators made the blood-contacting layer of the membrane out of biocompatible materials.

AHA

21 Sep 2021

End-stage heart failure patients, particularly female patients, may just have a new lease on life ahead as French artificial heart maker Carmat announced Tuesday that it had successfully implanted its Aeson artificial heart into the chest cavity of a 57-year-old woman.

“This 3rd implant in the U.S. was a landmark event not only because it allowed us to finalize the enrollment of the first cohort of patients of the EFS, but very importantly because it is the first time ever that our device has helped a woman suffering from heart failure. This achievement confirms that the size limitations for adults are minimal, which makes us very confident in Aeson’s potential to become a therapy of choice for a broad patient population,” said Carmat Chief Executive Officer Stéphane Piat.

What once seemed like science fiction now appears to be on the cusp of reality. Cases like this one point to the future, where bioprosthetic hearts could one day be a therapeutic alternative for patients with end-stage biventricular heart failure.

Paris-based Carmat is developing what it says is the world’s first physiological artificial heart that is highly hemocompatible, pulsatile and self-regulated. The company implanted the first Aeson artificial heart in its U.S.-based clinical trial on July 15 at Duke University Hospital. Today’s recipient is the third individual and first woman to receive what the company calls the world’s most advanced total artificial heart. The implantation was performed by a team of surgeons led by Dr. Mark S. Slaughter, professor and chair of the cardiovascular and thoracic surgery department at the University of Louisville and UofL physician at Jewish Hospital in Louisville, Ky.

The study’s primary endpoint is patient survival at 180 days post-implant or successful cardiac transplantation within 180 days of the implant. A total of 10 transplant-eligible patients are expected to be enrolled in the trial.

Carmat’s ultimate aim is not only to buy time but also to make Aeson the first alternative to a heart transplant, noting that these can be hard to come by due to a shortfall in available human grafts.

Slaughter also spoke to the importance of today’s milestone.

“The Aeson artificial heart is compact enough to fit inside smaller chest cavities, more frequently found in women, which gives hope to a wider variety of men and women waiting for a heart transplant and increases the chances for success,” he said, adding that his department continues to be impressed by the performance of the device.

The bioprosthetic offers patients waiting for heart transplants a better quality of life. The Aeson weighs 4 kilograms and is powered by two battery packs that provide approximately four hours of charge time before it has to be connected to a main power supply. It consists of sensors that detect blood pressure, thus allowing an algorithm to control blood flow in real-time.

In December 2020, Carmat received a CE marking for the Aeson, allowing the company to market it in the EU as a bridge to a transplant. The only artificial heart approved for use in the U.S. is SynCardia’s Temporary Total Artificial Heart (TAH), which has a “fixed beat” rather than autonomously adjusting to the patient's physical activity.

Market research firm IDTechEx projects that the cardiovascular disease technology market will be worth more than $40 billion by 2030.

19 Jul 2021

The company received CE marking for its artificial heart as a bridge to transplant in December last year

The implant is the company's first sale ever since it was created in 2008.(Credit: StockSnap from Pixabay)

French company CARMAT has announced the first implant of its Aeson bioprosthetic artificial heart in a commercial setting in Italy.

The implant, which was done at the Azienda Ospedaliera dei Colli hospital in Naples, is expected to lead to the company’s commercial development.

For CARMAT, the implant is also its first sale ever since it was created in 2008.

The company plans to focus its Aeson artificial heart marketing efforts on Germany this year, in line with its strategy. In December last year, the company received CE marking for its artificial heart as a bridge to transplant.

CARMAT chief executive officer Stéphane Piat said: “The first commercial implant of the Aeson heart is a major milestone in CARMAT’s history. It paves the way for a large number of patients to gradually access our therapy, and is the culmination of many years of work for our teams and our partners.

Designed to replace ventricles of native heart, the Aeson TAH is indicated as a bridge to transplant in patients suffering from end-stage biventricular heart failure and who could undergo heart transplant in the 180 days following device implantation.

CARMAT intends to address the shortfall in heart transplants for people suffering from irreversible end-stage heart failure, with the development of its total artificial heart, Aeson.

Aeson consists of the implantable bioprosthesis and a portable external power supply system to which it is continuously connected.

Currently, the device available within the framework of clinical trials in the US.

Stéphane Piat said: “The feedback we are receiving, both within the framework of our clinical trials, notably very recently in the United States, and in our discussions with European hospitals as part of Aeson’s commercialization, makes us very confident that our Aeson artificial heart is a “game changer” and offers unique benefits to patients, compared to all existing therapies.”

100 Deals associated with Harbor Diversified, Inc.

Login to view more data

100 Translational Medicine associated with Harbor Diversified, Inc.

Login to view more data

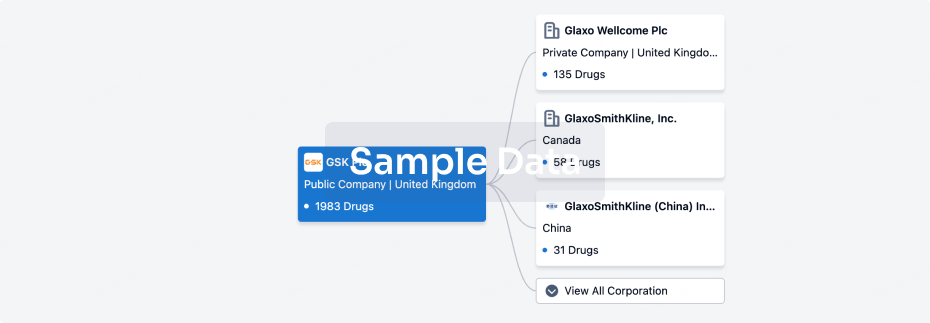

Corporation Tree

Boost your research with our corporation tree data.

login

or

Pipeline

Pipeline Snapshot as of 23 Feb 2026

The statistics for drugs in the Pipeline is the current organization and its subsidiaries are counted as organizations,Early Phase 1 is incorporated into Phase 1, Phase 1/2 is incorporated into phase 2, and phase 2/3 is incorporated into phase 3

Other

8

Login to view more data

Current Projects

| Drug(Targets) | Indications | Global Highest Phase |

|---|---|---|

Triolex ( ERK x NKRF ) | Rheumatic Fever More | Discontinued |

HE-3235 ( AR ) | Breast Cancer More | Discontinued |

Fluasterone ( NF-κB ) | Multiple Sclerosis More | Discontinued |

Immunitin ( AR ) | HIV Infections More | Pending |

HE-3210 | Radiation Injuries More | Pending |

Login to view more data

Deal

Boost your decision using our deal data.

login

or

Translational Medicine

Boost your research with our translational medicine data.

login

or

Profit

Explore the financial positions of over 360K organizations with Synapse.

login

or

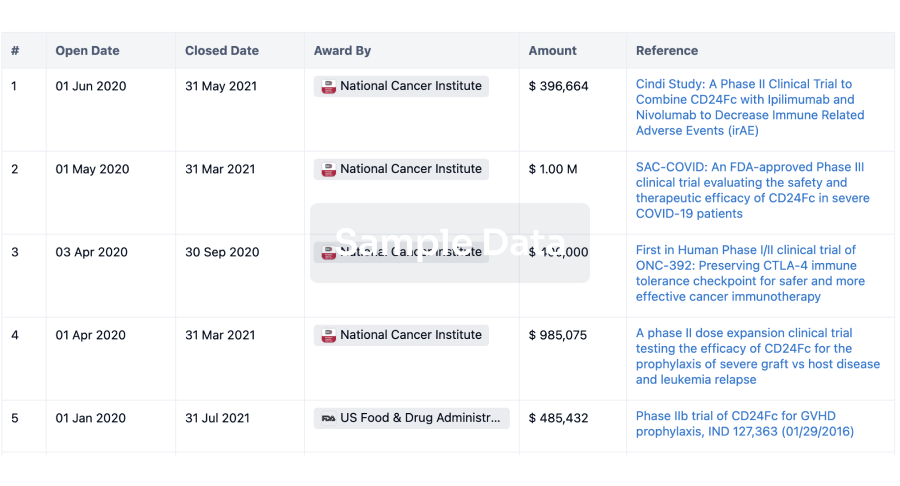

Grant & Funding(NIH)

Access more than 2 million grant and funding information to elevate your research journey.

login

or

Investment

Gain insights on the latest company investments from start-ups to established corporations.

login

or

Financing

Unearth financing trends to validate and advance investment opportunities.

login

or

AI Agents Built for Biopharma Breakthroughs

Accelerate discovery. Empower decisions. Transform outcomes.

Get started for free today!

Accelerate Strategic R&D decision making with Synapse, PatSnap’s AI-powered Connected Innovation Intelligence Platform Built for Life Sciences Professionals.

Start your data trial now!

Synapse data is also accessible to external entities via APIs or data packages. Empower better decisions with the latest in pharmaceutical intelligence.

Bio

Bio Sequences Search & Analysis

Sign up for free

Chemical

Chemical Structures Search & Analysis

Sign up for free