Request Demo

Last update 06 Dec 2025

BioNTech SE

Last update 06 Dec 2025

Overview

Basic Info

Introduction BioNTech SE is a company that specializes in developing immunotherapies for the treatment of cancer and other severe illnesses. Their product pipeline includes BNT162b2, BNT161, BNT164, FixVac, iNeST, RiboMabs, CAR-T Cells, TCRs, and Next-Gen CP Immunomodulators. The company was established in 2008 by Christopher Huber, Oezlem Tuereci, and Ugur Sahin and is based in Mainz, Germany. |

Tags

Neoplasms

Digestive System Disorders

Respiratory Diseases

Bispecific antibody

mRNA vaccine

Therapeutic vaccine

Disease domain score

A glimpse into the focused therapeutic areas

No Data

Technology Platform

Most used technologies in drug development

No Data

Targets

Most frequently developed targets

No Data

| Top 5 Drug Type | Count |

|---|---|

| mRNA vaccine | 26 |

| Prophylactic vaccine | 20 |

| Bispecific antibody | 16 |

| Therapeutic vaccine | 11 |

| Monoclonal antibody | 10 |

| Top 5 Target | Count |

|---|---|

| SARS-CoV-2 S protein | 4 |

| CD39 x PD-1 | 3 |

| CLDN6(Claudin 6) | 3 |

| 4-1BB x CLDN18.2 | 2 |

| 4-1BB x PDL1 | 2 |

Related

93

Drugs associated with BioNTech SETarget |

Mechanism SARS-CoV-2 S protein modulators [+1] |

Active Org. |

Originator Org. |

Inactive Indication- |

Drug Highest PhaseApproved |

First Approval Ctry. / Loc. United Kingdom |

First Approval Date02 Dec 2020 |

Target |

Mechanism 4-1BB agonists [+1] |

Active Org. |

Originator Org. |

Active Indication |

Inactive Indication |

Drug Highest PhasePhase 3 |

First Approval Ctry. / Loc.- |

First Approval Date- |

Target- |

Mechanism Immunostimulants |

Active Org. |

Originator Org. |

Active Indication |

Inactive Indication- |

Drug Highest PhasePhase 3 |

First Approval Ctry. / Loc.- |

First Approval Date- |

150

Clinical Trials associated with BioNTech SENCT07221149

ROSETTA Gastric-204: A Blinded, Randomized, Phase 2/3 Study of Pumitamig in Combination With Chemotherapy Versus Nivolumab in Combination With Chemotherapy in Participants With Previously Untreated Advanced or Metastatic Gastric, Gastroesophageal Junction, or Esophageal Adenocarcinoma

The purpose of this study is to evaluate the safety and efficacy of Pumitamig in combination with chemotherapy versus Nivolumab in combination with chemotherapy in participants with previously untreated advanced or metastatic gastric, gastroesophageal junction, or esophageal adenocarcinoma

Start Date09 Mar 2026 |

Sponsor / Collaborator |

NCT07221357

ROSETTA CRC-203: A Blinded, Randomized Phase 2/3 Study of Pumitamig in Combination With Chemotherapy Versus Bevacizumab in Combination With Chemotherapy in Participants With Previously Untreated, Unresectable, or Metastatic Colorectal Cancer

The purpose of this study is to evaluate the safety and efficacy of pumitamig in combination with chemotherapy versus bevacizumab in combination with chemotherapy in participants with previously untreated, unresectable, or metastatic colorectal cancer

Start Date04 Mar 2026 |

Sponsor / Collaborator |

NCT07255404

A Phase II, Multi-site, Randomized, Open-label, Trial of BNT327 in Combination With Chemotherapy in Patients With Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer

This study will enroll adults with confirmed metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC, systemic PDAC treatment naïve), Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS) 0-1, and adequate organ function. Participants will receive pumitamig (BNT327) in combination with chemotherapy.

Start Date01 Dec 2025 |

Sponsor / Collaborator  BioNTech SE BioNTech SE [+2] |

100 Clinical Results associated with BioNTech SE

Login to view more data

0 Patents (Medical) associated with BioNTech SE

Login to view more data

135

Literatures (Medical) associated with BioNTech SE01 Oct 2025·ADVANCES IN THERAPY

COVID-19-Related Healthcare Resource Utilisation and Costs in Paediatric Patients in Germany: A Population-Based Study

Article

Author: Nguyen, Jennifer ; Gowman, Hannah ; Seif, Monica ; Rai, Kiran K ; Yang, Jingyan ; Massey, Lucy ; Schmetz, Andrea ; Volkman, Hannah

INTRODUCTION:

There is limited evidence on the economic burden of COVID-19 in Germany. This study aims to quantify healthcare resource utilisation (HCRU) and direct medical costs associated with COVID-19 in paediatrics in Germany.

METHODS:

This was a population-based retrospective cohort study using data from the German Statutory Health Insurance (SHI) claims database to define outpatient (April 2020 to December 2021) and hospitalised (April 2020 to October 2022) cohorts of paediatric patients (aged 1-17 years) with a COVID-19 diagnosis.

RESULTS:

In the outpatient cohort (n = 104,656), most (77%) patients had ≥ 2 COVID-19-related general practitioner (GP) visits and 29% had ≥ 1 specialist visit during their diagnosis quarter. Outpatient resource use was greater in high-risk patients. When stratified by age, a greater proportion of children aged 1-4 years had ≥ 2 GP consultations, with specialist visits more common in those aged 5-11 years. The median cost per COVID-19 diagnosis quarter per patient was €192. Among the hospitalised cohort (n = 3129), the median general inpatient length of hospital stay (LoS) per patient per admission was 6.0 days; LoS was highest in those aged 5-11 years (7.0 days), at high risk (7.0 days) and during Alpha and Omicron predominance (both 7.0 days). The median cost per admission per patient was €12,503. Admission to critical care was observed in 13%, in whom the median cost per hospitalisation was €21,193.

CONCLUSIONS:

COVID-19-associated HCRU and costs among the paediatric population in Germany are non-negligible, driven largely by hospitalisations, particularly those who had a critical care admission and were at high risk.

01 Oct 2025·Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer

Claudin 6 is a suitable target for CAR T-cell therapy in atypical teratoid/rhabdoid brain tumors and other pediatric solid tumors

Article

Author: Duarte, João H ; Sinn, Bruno Valentin ; Gaida, Matthias Martin ; Wilson, Cullen ; Laible, Mark ; Madsen, Peter J ; Wingerter, Arthur ; Sahin, Ugur ; Patterson, Luke ; Feldner, Anja ; Flemmig, Carina ; Stern, Allison ; Wöll, Stefan ; Türeci, Özlem ; Beaubien, Ezra ; Stanulla, Martin ; Harvey, Kyra ; Storm, Phillip B ; Griffin, Crystal ; Schlitter, Anna Melissa ; Foster, Jessica B ; Dickson, Conor ; Holtemeyer, Saskia ; Frohns, Florian ; Faber, Jörg ; Resnick, Adam C ; Martinez, Daniel ; Joshi, Nikhil ; Hillemanns, Peter ; Hajeebu, Sreehita

Background:

Solid tumors comprise approximately 60% of all pediatric cancers. Relapsed or refractory tumors of the central nervous system (CNS), such as atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumors (AT/RTs), are the leading cause of death in children with cancer. Claudin 6 (CLDN6)-specific chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells have demonstrated activity in preclinical and clinical studies in various solid adult cancers. However, the suitability of CLDN6 as a target in pediatric tumors and their susceptibility to CAR T-cell therapy has yet to be established. This study aimed to evaluate the suitability of CLDN6 as a target for CAR T-cell therapy of pediatric solid tumors.

Methods:

Immunohistochemical CLDN6 expression was assessed in fetal normal tissues (n=91), pediatric normal tissues (n=157), and two sets of pediatric tumor tissues (n=527 and n=49) using a combined score that includes the percentage of stained cells with a 4-point intensity scale (0 to 3+). The antitumor activity of CLDN6 RNA-transduced CAR T cells against AT/RT cell lines was assessed with in vitro assays and in immunodeficient NOD-SCID-γc–/– (NSG) mouse models bearing orthotopic xenograft tumors.

Results:

Membranous CLDN6 expression, as detected by immunohistochemistry, was widely observed in fetal tissues but was absent in almost all non-malignant pediatric tissues, except for very rare, scattered cells with 1+ to 2+ intensity in kidney, pancreas, pituitary, and salivary gland tissues. Membranous CLDN6 expression was frequently detected in a subset of the pediatric tumor entities, including germ cell tumors (93% of samples with CLDN6-positive cells), nephroblastoma (64%), extracranial malignant rhabdoid tumors (50%), and AT/RTs (39%). In CLDN6-positive samples, CLDN6 was generally expressed with 2+ or 3+ intensity in substantial proportions of the cancer cells. Strong CLDN6 expression was also detected in single samples of hepatoblastoma, Ewing sarcoma/other embryonal tumors, and osteosarcoma.In experimental models, CLDN6-CAR T cells led to antigen-specific killing of endogenously CLDN6-expressing AT/RT cell lines in vitro and exhibited potent and specific antitumor activity in mice bearing orthotopic CLDN6-expressing AT/RT xenograft tumors.

Conclusions:

These results support CLDN6 as an oncofetal cell-surface antigen that may be suitable for CAR T-cell targeting in pediatric solid tumors, including those of the CNS.

16 Sep 2025·BIOCHEMISTRY

A Structurally Divergent Class Ia Ribonucleotide Reductase from a Tick-Borne Pathogen

Article

Author: Palowitch, Gavin M. ; Allen, Benjamin D. ; Lin, Chi-Yun ; Laremore, Tatiana N. ; Hu, Kai ; Peduzzi, Olivia M. ; Krebs, Carsten ; Boal, Amie K. ; Silletti, Steve ; Wheeler, Alyssa ; Komives, Elizabeth A. ; Bollinger, J. Martin ; Silakov, Alexey ; Gajewski, John P.

Ribonucleotide reductases (RNRs) generate 2'-deoxynucleotides for DNA biosynthesis, a reaction essential to all life. Class I RNRs have two subunits, α and β. α binds and reduces the substrate, whereas β oxidizes one of the cysteines in α to a C3'-H-bond-cleaving thiyl radical to begin the reaction. The α-Cys oxidant in β is variously a tyrosyl radical (Y•) generated by a diiron or dimanganese cluster, a high-valent dimetal cluster [Mn(IV)/Fe(III) or Mn2(IV/III)], or a dihydroxylphenylalanine (DOPA) radical that operates without need of a transition metal. The metal (in)dependence of the Cys oxidant in β correlates loosely with sequence-similarity groupings. We show here that Francisella hispaniensis (Fh) β, which lies within an uncharacterized sequence cluster that contains orthologs from multiple human pathogens, harbors a Fe2(III/III)/Y• cofactor, as in class Ia RNRs from eukaryotes and Escherichia coli. Fh β has several unusual structural features that may reflect adaptation to the bacterium's environment(s). In its apo form, an unwound helix everts a metal ligand toward solvent, and the radical-harboring Y points away from the diiron cluster. An additional aromatic residue (W194), conserved within the sequence cluster, is found close to the universally conserved W37, which is thought to mediate α-Cys oxidation in all class I enzymes. The Y• in resting β is remarkably resistant to reduction by hydroxyurea but becomes 8000 times more sensitive when β is engaged in turnover with α. These structural and functional distinctions could be counter measures against host redox defenses that would target the pathogen's RNR and its cofactor.

2,349

News (Medical) associated with BioNTech SE06 Dec 2025

Selective Treg modulator gotistobart (BNT316/ONC-392) showed a reduction in the risk of death by more than half compared to standard of care chemotherapy and a manageable safety profile in the first of two stages of the global Phase 3 trial PRESERVE-003 in patients with squamous non-small cell lung cancer (“sqNSCLC”) who have progressed on prior immunotherapy plus chemotherapy Median OS with gotistobart has not been reached at almost 15 months of follow-up, compared to a median OS of 10 months observed with chemotherapy As a chemotherapy-free monotherapy, gotistobart has the potential to become an alternative to traditional cytotoxic treatment for a patient population with high unmet medical need Gotistobart was granted Fast Track Designation by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (“FDA”) for the treatment of patients with metastatic NSCLC whose disease progressed on prior anti-PD-(L)1 therapy

MAINZ, Germany, and ROCKVILLE, USA, December 6, 2025 (GLOBE NEWSWIRE) -- BioNTech SE (Nasdaq: BNTX, “BioNTech”) and OncoC4, Inc. (“OncoC4”) today presented data from the non-pivotal dose-confirmation stage of the global randomized Phase 3 trial PRESERVE-003 (NCT05671510) for gotistobart (also known as BNT316 or ONC-392), a tumor microenvironment-selective regulatory T cell (“Treg”) depletion candidate, targeting CTLA-4 in patients with metastatic squamous non-small cell lung cancer (sqNSCLC). Gotistobart demonstrated a clinically meaningful overall survival (“OS”) benefit compared to standard-of-care chemotherapy and a manageable safety profile in sqNSCLC patients whose disease had progressed following anti-PD-(L)1 therapy and platinum-based chemotherapy. Data from the non-pivotal stage of the trial are being presented today in an oral presentation at the IASLC ASCO 2025 North America Conference on Lung Cancer, hosted by the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer in Chicago, Illinois, USA.

“With a median survival of less than a year, advanced squamous NSCLC remains an aggressive and difficult-to-treat lung cancer1,2. Survival outcomes have improved in recent years due to advances in immunotherapy and combination regimens. However, patients who progress on anti-PD-(L)1 inhibitor treatment face a poor prognosis, leaving them only with the option of chemotherapy or palliative care,” said Byoung Chul Cho, M.D., Ph.D., Lead Investigator and Professor at the Division of Medical Oncology, Yonsei Cancer Center, Seoul. “We are encouraged by the median overall survival still not being reached for patients treated with gotistobart at almost 15 months of follow-up, and we are excited to continue to investigate the candidate’s potential in the ongoing pivotal stage of the trial.”

The analysis from the non-pivotal stage of the global Phase 3 trial included 45 metastatic sqNSCLC patients who received gotistobart as monotherapy, compared with 42 metastatic sqNSCLC patients who received chemotherapy (docetaxel) as second or later line of systemic therapy. At the data cut-off on August 8, 2025, 87 patients with sqNSCLC had been randomized to either gotistobart 6 mg/kg with two 10 mg/kg loading doses (N=45) or docetaxel 75 mg/m2 (N=42). The OS rate at 12 months was 63.1% for gotistobart compared to 30.3% for docetaxel. At a median follow-up of 14.5 months, patients in the gotistobart treatment arm had not yet reached the median OS, while the docetaxel treatment arm achieved a median OS of 10 months. The data showed that the gotistobart arm reduced the risk of death by 54% compared to the docetaxel treatment arm (HR=0.46, 95% CI: 0.25–0.84; nominal p-value 0.0102). The safety profile of gotistobart was consistent with previously established data and remained manageable. Grade ≥3 treatment-related adverse events (“AEs”) were reported in 19/45 (42.2%) patients in the gotistobart treatment arm versus 20/41 (48.8%) patients in docetaxel treatment arm. The pivotal stage of the Phase 3 trial is ongoing in more than 160 sites globally.

“Gotistobart is designed to selectively deplete tumor-infiltrating regulatory T cells within the tumor microenvironment. The data presented today showed encouraging signals for our approach to translating our deep understanding of the immune system into meaningful survival benefits for patients with squamous NSCLC,” said Prof. Özlem Türeci, M.D., Co-Founder and Chief Medical Officer at BioNTech. “With its unique mode of action, we are investigating gotistobart both as a monotherapy and in synergistic combinations with other modalities. Our goal is to deliver transformative treatment options that provide meaningful and durable benefits for patients.”

“Gotistobart represents a step forward in our goal of offering a chemotherapy-free treatment option for patients with advanced squamous NSCLC, a population with limited therapeutic choices and a lack of actionable biomarkers to guide treatment,” said Pan Zheng, M.D., Ph.D., Chief Medical Officer and Co-Founder at OncoC4. “The encouraging data presented today underscore the potential of gotistobart to address the unmet medical needs. We look forward to continuing to jointly explore the potential of the novel mechanism of action and advance clinical development for patients who have not benefited from currently approved immunotherapy.”

About the PRESERVE-003 trialPRESERVE-003 (NCT05671510) is a two-stage, open-label Phase 3 trial evaluating the efficacy and safety of gotistobart as monotherapy compared to the standard-of-care chemotherapy (docetaxel) in sqNSCLC patients, who have progressed on PD-(L)1 inhibitors and platinum-based chemotherapy. The non-pivotal stage of the trial originally included all NSCLC patients. The ongoing pivotal stage is currently enrolling patients with sqNSCLC. During the ongoing pivotal stage, approximately 500 patients are planned to be enrolled at clinical sites in various countries and regions, including Australia, Belgium, Canada, China, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, South Korea, Türkiye, the United Kingdom and the United States. The primary endpoint is overall survival. Secondary endpoints include overall response rate, progression-free survival and safety profile.

About gotistobart (BNT316/ONC-392)Gotistobart (BNT316/ONC-392) is a tumor microenvironment-selective Treg depletion candidate developed jointly by BioNTech and OncoC4. As a pH-sensitive monoclonal antibody, gotistobart is designed to enable CTLA-4 protein recycling. After binding to the CTLA-4 receptor on the cell surface, the complex is internalized, and the pH change causes the antibody to unbind, allowing CTLA-4 to return to the surface to preserve the immune checkpoint function at peripheral organs and to enhance anti-tumor immunity in the tumor microenvironment3. Gotistobart is currently in late-stage clinical development as monotherapy and as a component of combination therapy in various cancer indications. Gotistobart has received Fast Track Designation from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (“FDA”) in 2022 for the treatment of patients with metastatic NSCLC whose disease progressed on prior anti-PD-(L)1 therapy and Breakthrough Therapy Designation from China’s National Medical Products Administration (“NMPA”) in 2025.

Multiple trials are ongoing, including a pivotal Phase 3 trial (PRESERVE-003; NCT05671510) in patients with metastatic squamous NSCLC, a Phase 2 trial (PRESERVE-004; NCT05446298) in patients with platinum-resistant ovarian cancer, a Phase 2 trial (PRESERVE-006; NCT05682443) in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer, and a Phase 1/2 open-label dose escalation trial (PRESERVE-001; NCT04140526) in patients with advanced solid tumors. BioNTech also evaluates gotistobart in combination with its mRNA cancer immunotherapy candidate BNT116 in a signal seeking cohort of the ongoing Phase 1 trial (LuCa-MERIT-1; NCT05142189).

About NSCLCNon-small cell lung cancer (“NSCLC”) covers all epithelial lung cancers other than small cell lung cancer and includes squamous cell carcinoma, large cell carcinoma, and adenocarcinoma of the lung. It is the most common type of lung cancer, accounting for up to 85% of cases4, with risk factors ranging from smoking to asbestos exposure and pulmonary fibrosis5. Around 25% of all lung cancer cases are attributed to the subtype squamous cell carcinoma (SCC)6. With a 5-year relative survival rate of 15% and a median overall survival of 11 months in the United States (2000-2017), sqNSCLC is a devastating disease with limited treatment options7. Current standard-of-care includes surgery and radiotherapy in combination with chemotherapy8. Treatment options for second-line therapy after first-line immunotherapy and chemotherapy are limited to chemotherapy or palliative therapy in advanced/metastatic sqNSCLC, and remain more limited than for non-squamous NSCLC5.

About BioNTechBiopharmaceutical New Technologies (BioNTech) is a global next generation immunotherapy company pioneering novel investigative therapies for cancer and other serious diseases. BioNTech exploits a wide array of computational discovery and therapeutic modalities with the intent of rapid development of novel biopharmaceuticals. Its diversified portfolio of oncology product candidates aiming to address the full continuum of cancer includes mRNA cancer immunotherapies, next-generation immunomodulators and targeted therapies such as antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) and innovative chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell therapies. Based on its deep expertise in mRNA development and in-house manufacturing capabilities, BioNTech and its collaborators are researching and developing multiple mRNA vaccine candidates for a range of infectious diseases alongside its diverse oncology pipeline. BioNTech has established a broad set of relationships with multiple global and specialized pharmaceutical collaborators, including Bristol Myers Squibb, Duality Biologics, Fosun Pharma, Genentech, a member of the Roche Group, Genmab, MediLink, OncoC4, Pfizer and Regeneron.

For more information, please visit www.BioNTech.com.

BioNTech Forward-Looking StatementsThis press release contains forward-looking statements within the meaning of the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995, as amended, including, but not limited to, statements concerning: the collaboration with OncoC4; BioNTech and OncoC4’s ability to successfully co-develop and co-commercialize gotistobart (also known as BNT316 or ONC-392), if approved; the rate and degree of market acceptance of gotistobart, if approved; the initiation, timing, progress, and results of BioNTech’s research and development programs, including data from the non-pivotal dose-confirmation stage of the global randomized Phase 3 trial PRESERVE-003 and statements regarding the expected timing of initiation, enrollment, and completion of trials and related preparatory work and the availability of results, and the timing and outcome of applications for regulatory approvals and marketing authorizations, including expectations regarding the potential indications in which gotistobart may be approved, if at all; the targeted timing and number of additional potentially registrational trials, and the registrational potential of any trial BioNTech may initiate; and discussions with regulatory agencies. In some cases, forward-looking statements can be identified by terminology such as “will,” “may,” “should,” “expects,” “intends,” “plans,” “aims,” “anticipates,” “believes,” “estimates,” “predicts,” “potential,” “continue,” or the negative of these terms or other comparable terminology, although not all forward-looking statements contain these words.

The forward-looking statements in this press release are based on BioNTech’s current expectations and beliefs of future events and are neither promises nor guarantees. You should not place undue reliance on these forward-looking statements because they involve known and unknown risks, uncertainties, and other factors, many of which are beyond BioNTech’s control and which could cause actual results to differ materially and adversely from those expressed or implied by these forward-looking statements. These risks and uncertainties include, but are not limited to: the uncertainties inherent in research and development, including the ability to meet anticipated clinical endpoints, commencement and/or completion dates for clinical trials, regulatory submission dates, regulatory approval dates and/or launch dates, as well as risks associated with clinical data, and including the possibility of unfavorable new preclinical, clinical or safety data and further analyses of existing preclinical, clinical or safety data; the nature of clinical data, which is subject to ongoing peer review, regulatory review and market interpretation; the impact of tariffs and escalations in trade policy; competition related to BioNTech’s product candidates; the timing of and BioNTech’s ability to obtain and maintain regulatory approval for its product candidates; BioNTech’s ability to identify research opportunities and discover and develop investigational medicines; the ability and willingness of BioNTech’s third-party collaborators to continue research and development activities relating to BioNTech’s development candidates and investigational medicines; unforeseen safety issues and potential claims that are alleged to arise from the use of products and product candidates developed or manufactured by BioNTech; BioNTech’s and its collaborators’ ability to commercialize and market its product candidates, if approved; BioNTech’s ability to manage its development and related expenses; regulatory and political developments in the United States and other countries; BioNTech’s ability to effectively scale its production capabilities and manufacture its products and product candidates; and other factors not known to BioNTech at this time.

You should review the risks and uncertainties described under the heading “Risk Factors” in BioNTech’s Report on Form 6-K for the period ended September 30, 2025 and in subsequent filings made by BioNTech with the SEC, which are available on the SEC’s website at www.sec.gov. These forward-looking statements speak only as of the date hereof. Except as required by law, BioNTech disclaims any intention or responsibility for updating or revising any forward-looking statements contained in this press release in the event of new information, future developments or otherwise.

About OncoC4 Based in Rockville, Maryland, OncoC4 is a privately held, late clinical-stage biopharmaceutical company that is actively engaged in the discovery and development of novel biologicals for the treatment of cancer and immunological diseases. OncoC4’s pipeline features assets with first-in-class and best-in-class potential targeting both novel and well validated targets across oncology and immunological diseases. Among them, AI-081 is a fully owned bispecific antibody candidate targeting PD-1 and VEGF. ONC-841 is a first-in-class anti-SIGLEC10 antibody currently in a Phase 2 trial for oncology indications and being explored for neurodegenerative diseases. OncoC4 has a strategic collaboration with BioNTech to co-develop gotistobart (BNT316/ONC-392), a tumor microenvironment-selective Treg depletion candidate targeting CTLA-4, in multiple solid tumor indications, including an ongoing pivotal clinical trial in squamous non-small cell lung cancer.

More information: www.oncoc4.com.

CONTACTS

BioNTech:

Investor RelationsDouglas Maffei, Ph.D.Investors@BioNTech.de

Media RelationsJasmina AlatovicMedia@BioNTech.de

OncoC4:Investor RelationsRyan Cuiir@oncoc4.com

Media RelationsHelen Schiltzhschiltz@oncoc4.com

1 Paz-Ares L, et al. (2018) Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy for squamous non-small-cell lung cancer. N Eng J Med. 379:2040-2051.2 Zhou, Caicun et al. (2024) A global phase 3 study of serplulimab plus chemotherapy as first-line treatment for advanced squamous non-small-cell lung cancer (ASTRUM-004), Cancer Cell, Volume 42, Issue 2, 198 - 208.e33 Zhang Y et al. (2019) Hijacking antibody-induced CTLA-4 lysosomal degradation for safer and more effective cancer immunotherapy. Cell Res. 29:609-627.4 Sung H. et al. (2021) Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71(3):209-2495 National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health (2025) Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Treatment (PDQ®)–Health Professional Version, online at: https://www.cancer.gov/types/lung/hp/non-small-cell-lung-treatment-pdq#_37_toc6 Zhang Y. et al. (2023) Global variations in lung cancer incidence by histological subtype in 2020: a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 24(11):1206-1218.7 Hu, Sheng et al. (2021) Prognosis and Survival Analysis of 922,217 Lung Cancer Patients from the US Based on the Most Recent Data from the SEER Database (April 15, 2021), International Journal of General Medicine, Volume 14, 9567-9588.8 American Cancer Society (2025) Treatment Choices for Non-small Cell Lung Cancer, by Stage, online at: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/lung-cancer/treating-non-small-cell/by-stage.html

Phase 3ImmunotherapyClinical ResultPhase 2Fast Track

04 Dec 2025

With a median cost exceeding USD 2 billion and a development timeline of 10-12 years, bringing a new drug to market can be a daunting and high-stakes endeavour for innovators. It may seem trifle when compared to annual sales of a Keytruda or Ozempic, however blockbusters represent a mere fraction of brands that have gained global success. The pharmaceutical landscape is filled with underperforming drugs, underscoring the high risk and caution that surround drug development efforts.

First, the cost reflects a successfully developed drug, not necessarily one that's commercialized, many fail or are discontinued. Second, each development stage is a risk point, with less than 15-20% of Phase I drugs reaching approval. Third, the long timeline cuts into the 20-year patent exclusivity, often leaving only 8–10 years to recoup investment.

Despite supplementary patents, NCE/NBE patent remains the holy grail as generic pharma more often than not challenge them via invalidation or non-infringement. And now with the proposed 100% tariffs on imported branded medicine in US, this may just exacerbate the situation.

Contract Research, Development, and Manufacturing Organizations (

CRDMOs

) have eased the drug development burden by offering faster, cost-effective solutions across the value chain. This has helped them capture roughly a third (USD 100–120 bn) of global R&D spend, with outsourcing growing at ~10%, outpacing overall R&D growth (~5%). Their data-backed validation, unbiased guidance on project viability, and ability to manage innovator fatigue are critical to both successful development and timely rejection.

‘Follow the molecule’ strategy have also allowed

CDMO

stake claim for late stage and commercial manufacturing, creating an additional ~USD 75bn global business. However, building trust around IP protection, scientific expertise, and advanced technologies requires significant upfront investment and time, as high as 12-24 months for customer qualification.

While US and European

CRDMOs

had a strategic advantage due to proximity to key clients, India and China steadily gained ground, leveraging strengths in pharmaceutical science, talent, and cost efficiency. China moved faster, driven by entrepreneurship and early private capital.

Riding on the success of WuXi group, Pharmaron, Tigermed and many others, particularly in complex biological drug development, it grew at an astoundingly consistent rate of late teens to early twenties in last 10 years and achieved a significant 13–15% global market share.

India, in contrast, grew modestly between 2000–2015, mostly through internal cash flows and debt. A structural shift began post-2015, fuelled by private capital and government involvement. However, the delay in their onset and gestation period between investment to harvesting revenues have resulted in India’s global share of sub 4% thus far. On the positives though, this should breach 6–7% by 2030. Coupled with ~10% global market growth, this could translate to an 18–20% CAGR for India—mirroring China’s past trajectory.

In the recent past, Indian business benefitted from ‘China + 1’ strategy as innovators derisked their China exposure. Even the proposed BIOSECURE Act reemphasizes outsourcing diversification. However, two structural challenges demand a strong focus to drive this long-term growth.

First, despite strengths in medicinal chemistry, Indian players lack depth in end-to-end biological drug development—a key gap as biologics like monoclonal antibodies, GLP-1s, and peptides are set to outpace small molecules in growth (8–10% vs. 2–4%). While players like

Syngene

, Aragen, and Anthem show promise, scale is still evolving.

Secondly, majority of Indian players either have a significant control in research and clinical development or late-stage manufacturing. In some ways, we are losing sight of ‘follow-the-molecule’ strategy or doing a late stage catch-up, which otherwise could create multi-factor growth avenue.

Western players employed M&A as the major growth lever to acquire capability, scale, customers and geographical diversification. Global majors – Lonza, AMRI, Catalent and Patheon did an astounding nearly 50 acquisitions between them. Indian companies have largely avoided M&A-led growth. While this cautious approach has worked, scaling up now demands aggressive capability-building, talent acquisition, and selective M&A, specially in biologics to unlock the next phase of growth.

Early-stage biotech is a sensitive area, especially for Indian and Chinese CRDMOs. Often with little to no revenue and dependent on government grants or VC/PE funding, these firms rely heavily on outsourcing.

In 2021 PE/VC funded an enormous USD 40-45bn to biotechs, and that has now become a sore comparison point as this is now in vicinity of USD 25 bn thereafter.

Proposed NIH budget cuts in the U.S. added pressure, though a Senate panel restored the USD 48 bn allocation. Despite negative sentiment, biotechs play a key role in Big Pharma’s pipeline through licensing and acquisitions (ref to table 1). Rather than losing this business, CRDMOs need balanced, risk-adjusted partnerships with biotechs.

India has a formidable

CRDMO

base with companies like Divi’s,

Syngene

, Aragen, Sai, Cohance (Suven), Aurigene,

Piramal Pharma

and many more with over USD 1.25 bn in

CAPEX

over the past 3 years (USD 500 mn in FY25 alone). With median asset turnover of 1.2–1.3x that should solve for the next billion and half in revenues. And the likelihood of BIOSECURE ACT becoming a law should only bolster India’s positioning further. Industry collaboration through new bodies like Innovative Pharma Services Organisation (IPSO) can align efforts on policy, synergy, and growth.

While the dynamic geopolitically situation remains unpredictable, the currently proposed tariffs on innovator medicine seem to have low to no impact on Indian CRDMO story thus far. Indian players typically compete either in research services or advanced intermediates or APIs in supply and not finished formulations like Switzerland, UK, Ireland and Germany. So, is USD 20–25 bn over the next decade possible? Yes—capital is available, capabilities are strong, and now it’s about moving faster.

Drug

Made by

Commercialized by (est. revenue)

Covishield

Oxford Uni. (Jenner)

AstraZeneca (~USD 10 bn)

Comirnaty

BioNTech

Pfizer (~USD 38 bn)

Zolgesma

AveXis

Novartis (USD 1.2 bn)

Welireg

Peloton

Merck (USD 509 mn year 1 sales)

Yeskarta

Kite Pharma

Gilead (USD 1.6 bn)

Calquence

Acerta Pharma

AstraZeneca (USD 2.5 bn)

Sources: NIH, Macquarie, SPARK, Company annual reports, analyst coverages.

The aritcle is written by

Shomil Pant

,

Principal

, Avendus Future Leaders Fund.

(

DISCLAIMER: The views expressed are solely of the author and ET Pharma.com does not necessarily subscribe to it. ET Pharma.com shall not be responsible for any damage caused to any person/organisation directly or indirectly)

By

Online Bureau

,

Acquisition

04 Dec 2025

Crescent Biopharma made a set of sweeping moves Thursday morning, notably with its strategy of bringing its PD-1xVEGF to China.

Boston-based Crescent signed a two-way deal with Kelun-Biotech, in which both companies will have access to some of each others’ assets. Crescent said that clinical trial preparation is underway and that it secured a $185 million private placement.

Investors appeared to appreciate Crescent’s moves. Its share price

$CBIO

rose 15% in premarket trading.

The news begins with Crescent

out-licensing

the Greater China rights to its cancer drug candidate CR-001 to Kelun-Biotech. Kelun will pay Crescent $20 million upfront and up to $30 million in milestones for the rights to the PD-1xVEGF drug candidate.

The experimental medicine will enter Phase 1 in the first quarter of 2026. But that’s far behind frontrunners such as Summit Therapeutics, Bristol Myers Squibb and Merck. Among others, UK biotech

Ottimo Pharma

is also in the race, with expectations of getting IND clearance within the next four weeks.

Meanwhile, Crescent will get access to Kelun’s integrin beta-6 (ITGB6)-directed ADC, called SKB105/CR-003, which is also slated to enter Phase 1/2 monotherapy trials in solid tumors next quarter. For ex-Greater China rights to the ADC, Crescent will pay Kelun $80 million upfront and promise up to $1.25 billion in biobucks.

The two assets in this deal will first undergo monotherapy studies and then be studied in combination in the first half of 2027, Crescent said. It has other ADCs in development that it will also pair up with CR-001, including the PD-L1-directed CR-002.

Also on Thursday morning, Crescent said it nabbed a $185 million private placement from Forbion, Fairmount, ADAR1 and other investors.

These updates all take place six months after Crescent became a public biotech via a reverse merger with GlycoMimetics. Crescent is one of multiple spinouts from Paragon, an antibody discovery shop funded by Fairmount that has pumped out other companies like Apogee, Spyre and Jade.

Crescent and Kelun’s deal follows a trend of Western biotechs going to China to pick up new medicines. Such deals have accounted for nearly one-third of drug licensing pacts this year.

But the two-way deal also marks somewhat of a rarity in that Crescent is out-licensing its PD-1xVEGF to China rather than in-licensing its candidate from the country. Summit, Bristol Myers and Merck all got their investigational medicines in the hot class via Chinese biotechs

Akeso

, Biotheus and LaNova Medicines, respectively.

For Kelun, it marks its latest $1 billion-plus ADC pact. The Chengdu-based drug developer’s main Western partner is Merck, which has forged a couple ADC alliances with the biotech. The duo’s most advanced candidate, called sac-TMT, is now

headed to China’s health regulator

.

License out/inADCPhase 1

100 Deals associated with BioNTech SE

Login to view more data

100 Translational Medicine associated with BioNTech SE

Login to view more data

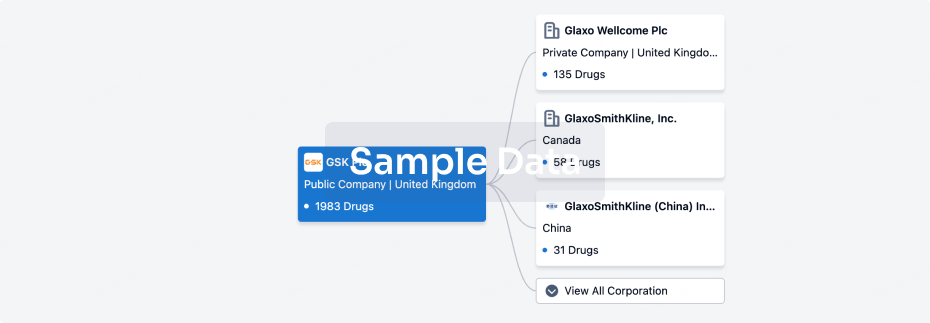

Corporation Tree

Boost your research with our corporation tree data.

login

or

Pipeline

Pipeline Snapshot as of 25 Jan 2026

The statistics for drugs in the Pipeline is the current organization and its subsidiaries are counted as organizations,Early Phase 1 is incorporated into Phase 1, Phase 1/2 is incorporated into phase 2, and phase 2/3 is incorporated into phase 3

Discovery

12

24

Preclinical

IND Application

2

20

Phase 1

Phase 2

24

5

Phase 3

Approved

1

61

Other

Login to view more data

Current Projects

| Drug(Targets) | Indications | Global Highest Phase |

|---|---|---|

Comirnaty-COVID-19 mRNA vaccine ( SARS-CoV-2 S protein ) | COVID-19 More | Approved |

Trastuzumab Pamirtecan ( HER2 x Top I ) | HR-positive/HER2-low Breast Carcinoma More | Phase 3 |

Gotistobart ( CTLA4 ) | metastatic non-small cell lung cancer More | Phase 3 |

Pumitamig ( PDL1 x VEGF-A ) | Turcot Syndrome More | Phase 2/3 |

BNT-113 ( E6 x HPV E7 ) | Recurrent Head and Neck Carcinoma More | Phase 2/3 |

Login to view more data

Deal

Boost your decision using our deal data.

login

or

Translational Medicine

Boost your research with our translational medicine data.

login

or

Profit

Explore the financial positions of over 360K organizations with Synapse.

login

or

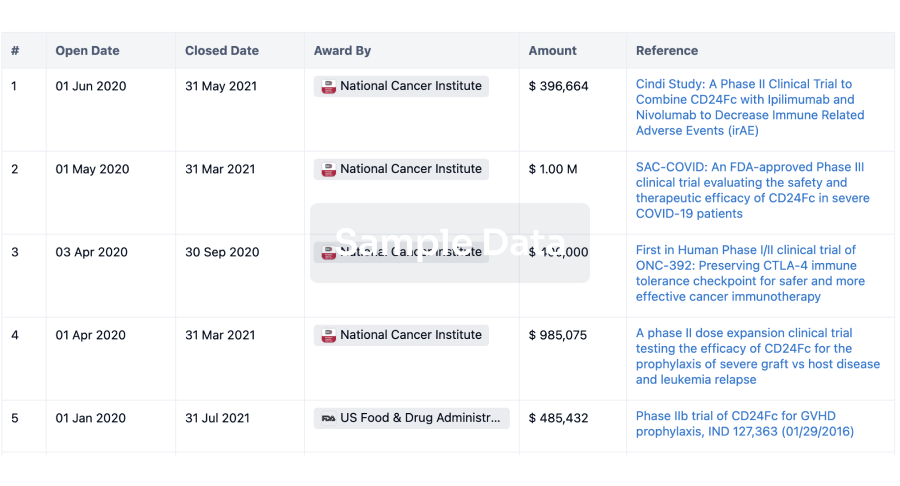

Grant & Funding(NIH)

Access more than 2 million grant and funding information to elevate your research journey.

login

or

Investment

Gain insights on the latest company investments from start-ups to established corporations.

login

or

Financing

Unearth financing trends to validate and advance investment opportunities.

login

or

AI Agents Built for Biopharma Breakthroughs

Accelerate discovery. Empower decisions. Transform outcomes.

Get started for free today!

Accelerate Strategic R&D decision making with Synapse, PatSnap’s AI-powered Connected Innovation Intelligence Platform Built for Life Sciences Professionals.

Start your data trial now!

Synapse data is also accessible to external entities via APIs or data packages. Empower better decisions with the latest in pharmaceutical intelligence.

Bio

Bio Sequences Search & Analysis

Sign up for free

Chemical

Chemical Structures Search & Analysis

Sign up for free