Request Demo

Last update 26 Dec 2025

Nirmatrelvir/Ritonavir

Last update 26 Dec 2025

Overview

Basic Info

Drug Type Small molecule drug |

Synonyms PF 07321332 plus ritonavir, 帕克斯洛维德, 帕昔洛韦 + [5] |

Action inhibitors |

Mechanism CYP3A inhibitors(Cytochrome P450 3A inhibitors), SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro inhibitors(SARS-CoV-2-3C-like-proteinase inhibitors) |

Therapeutic Areas |

Active Indication |

Inactive Indication- |

Originator Organization |

Active Organization |

Inactive Organization- |

License Organization |

Drug Highest PhaseApproved |

First Approval Date South Korea (27 Dec 2021), |

RegulationEmergency Use Authorization (United States), Emergency Use Authorization (India), Emergency Use Authorization (South Korea), Conditional marketing approval (China) |

Login to view timeline

Structure/Sequence

Molecular FormulaC23H32F3N5O4 |

InChIKeyLIENCHBZNNMNKG-OJFNHCPVSA-N |

CAS Registry2628280-40-8 |

View All Structures (2)

Related

61

Clinical Trials associated with Nirmatrelvir/RitonavirNCT07261085

A Real-world Study on the Effectiveness of Nirmatrelvir-ritonavir in Reducing Severe Outcomes From COVID-19

The purpose of this study is to learn about the effects of the study medicine called Paxlovid [nirmatrelvir-ritonavir/PF-07321332], for the potential treatment of COVID-19.

This study will use patient health records in Ontario, to find people who were sick with COVID-19 and visited a pharmacist to be treated, anytime from December 1st, 2022, to March 31st, 2024. To be included in our study, the people must be over 18 years of age and be registered in the Ontario health system for at least one year. People were not included in our study if they have been pregnant in the past year or have serious kidney or liver disease.

We will separate the people in the study into two groups: those who received treatment with Paxlovid [nirmatrelvir-ritonavir/PF-07321332] and those who received no treatment. We will monitor their healthcare visits or if they die for any reason, for up to 60 days after the date that they visited their pharmacist. Then we will compare participant experiences when they are taking the study medicine to when they are not. This will help us determine if the study medicine is effective.

This study will use patient health records in Ontario, to find people who were sick with COVID-19 and visited a pharmacist to be treated, anytime from December 1st, 2022, to March 31st, 2024. To be included in our study, the people must be over 18 years of age and be registered in the Ontario health system for at least one year. People were not included in our study if they have been pregnant in the past year or have serious kidney or liver disease.

We will separate the people in the study into two groups: those who received treatment with Paxlovid [nirmatrelvir-ritonavir/PF-07321332] and those who received no treatment. We will monitor their healthcare visits or if they die for any reason, for up to 60 days after the date that they visited their pharmacist. Then we will compare participant experiences when they are taking the study medicine to when they are not. This will help us determine if the study medicine is effective.

Start Date27 Oct 2025 |

Sponsor / Collaborator |

NCT07089680

Impact of Nirmatrelvir and Ritonavir (PAXLOVID?) on Mortality, Progression to Severe Disease, and Activities of Daily Living (ADL) Worsening in Long-term Care Hospitals (LTCHs) in Korea

The purpose of this study is to learn about the effects of the study medicine (called Paxlovid) for the possible treatment of COVID-19 in older adults who live in long-term care hospitals (LTCHs) in Korea. Researchers want to know whether Paxlovid lowers the chance of severe illness or death and helps people carry out their usual daily activities, remain free from aging and weakness, and maintain cognitive function.

This study is seeking participants who:

* are 60 years of age or older

* live in a long-term care hospital in Korea

* were diagnosed with COVID-19 on or after 14 January 2022, during the period when Paxlovid was available as part of routine care

* received Paxlovid within 5 days after their first COVID-19 symptoms (only for people in the Paxlovid group)

All participants in this study received their usual COVID-19 care. About half also received Paxlovid. Paxlovid was prescribed as part of routine care at the long-term care hospital, typically taken by mouth 2 times a day for 5 days.

The study team will compare the health results of people who received Paxlovid to those who did not, using similar parameters such as age, sex, and medical history. This will help the study team to understand whether Paxlovid makes a meaningful difference in stopping severe illness, death, or slow-down daily functioning.

Participants will not have any extra study visits or tests. The study team will only review information already recorded in their medical charts for up to 1 year after their COVID-19 symptom onset.

This study is seeking participants who:

* are 60 years of age or older

* live in a long-term care hospital in Korea

* were diagnosed with COVID-19 on or after 14 January 2022, during the period when Paxlovid was available as part of routine care

* received Paxlovid within 5 days after their first COVID-19 symptoms (only for people in the Paxlovid group)

All participants in this study received their usual COVID-19 care. About half also received Paxlovid. Paxlovid was prescribed as part of routine care at the long-term care hospital, typically taken by mouth 2 times a day for 5 days.

The study team will compare the health results of people who received Paxlovid to those who did not, using similar parameters such as age, sex, and medical history. This will help the study team to understand whether Paxlovid makes a meaningful difference in stopping severe illness, death, or slow-down daily functioning.

Participants will not have any extra study visits or tests. The study team will only review information already recorded in their medical charts for up to 1 year after their COVID-19 symptom onset.

Start Date18 Aug 2025 |

Sponsor / Collaborator |

NCT06397144

A PHASE 1, OPEN-LABEL, RANDOMIZED, SINGLE DOSE, CROSSOVER STUDY TO DETERMINE THE BE OF NIRMATRELVIR FOLLOWING ORAL ADMINISTRATION OF FDC TABLETS RELATIVE TO THE PAXLOVID® COMMERCIAL TABLETS IN HEALTHY ADULT PARTICIPANTS UNDER FASTED CONDITIONS

Medicines that may have different names or be made in different ways but have the same effect on the body are called bioequivalent.

The purpose of this study is to learn about the bioequivalence of nirmatrelvir plus ritonavir after taking 2 different combination tablet forms by mouth. These combination tablets are compared to the tablet formulation that is already in the market. This study will be done under fasted conditions in healthy adult participants.

This study is seeking participants who are:

* Male and non-pregnant female participants aged 18 years and above.

* with a body weight of more than 50 kilograms and Body Mass Index (BMI) between 16 to 32 kilograms per meter squared.

* are healthy as confirmed by medical history, physical examination, laboratory tests.

The study will also look at the safety and tolerability of nirmatrelvir plus ritonavir combination tablet and marketed tablet formulations in healthy adult participants.

The study will consist of 4 treatments:

Treatment A: Single oral dose of nirmatrelvir plus ritonavir 150 (1 × 150)/100 milligrams marketed tablets under fasted conditions (Reference 1) Treatment B (low dose strength): Single oral dose of nirmatrelvir plus ritonavir 150/100 milligrams (2 × [75/50 milligrams]) combination tablets under fasted conditions (Test 1) Treatment C: Single oral dose of nirmatrelvir/ritonavir 300 (2 × 150)/100 milligrams marketed tablets under fasted conditions (Reference 2) Treatment D (high dose strength): Single oral dose of nirmatrelvir/ritonavir 300/100 milligrams (2 × [150/50 milligrams]) combination tablets under fasted conditions (Test 2)

All treatments will be given under fasted conditions. Fasted condition means the participants would not have had anything to eat before taking the medicines.

Around 28 participants will be enrolled in the study. Healthy participants will be tested to see if they can be in the study within 28 days before receiving the study medicine. Selected participants will be admitted to the clinical research unit (CRU) one day before receiving the study medicine and will remain in the CRU until discharge after completing all the treatment periods.

On Day 1 of each period, participants will be given a single dose of study medicine nirmatrelvir/ritonavir 300/100 mg or 150/100 mg by mouth by chance. Study medicine will be given with approximately 240 milliliters of room temperature water under fasted conditions (overnight fast of at least 10 hours and no food until 4 hours after receiving the study medicine). Blood samples will be collected at different times of the day up to 48 hours after taking the study medicine. Participants will be discharged from the CRU on Day 3 of Period 4, after all the study related procedures have been completed.

A follow-up call will be made to participants around 28 to 35 days from receiving the final dose of the study medicine. The study will look at the experiences of participants receiving the study medicine. This will help to understand if the study medicine is safe and effective.

The purpose of this study is to learn about the bioequivalence of nirmatrelvir plus ritonavir after taking 2 different combination tablet forms by mouth. These combination tablets are compared to the tablet formulation that is already in the market. This study will be done under fasted conditions in healthy adult participants.

This study is seeking participants who are:

* Male and non-pregnant female participants aged 18 years and above.

* with a body weight of more than 50 kilograms and Body Mass Index (BMI) between 16 to 32 kilograms per meter squared.

* are healthy as confirmed by medical history, physical examination, laboratory tests.

The study will also look at the safety and tolerability of nirmatrelvir plus ritonavir combination tablet and marketed tablet formulations in healthy adult participants.

The study will consist of 4 treatments:

Treatment A: Single oral dose of nirmatrelvir plus ritonavir 150 (1 × 150)/100 milligrams marketed tablets under fasted conditions (Reference 1) Treatment B (low dose strength): Single oral dose of nirmatrelvir plus ritonavir 150/100 milligrams (2 × [75/50 milligrams]) combination tablets under fasted conditions (Test 1) Treatment C: Single oral dose of nirmatrelvir/ritonavir 300 (2 × 150)/100 milligrams marketed tablets under fasted conditions (Reference 2) Treatment D (high dose strength): Single oral dose of nirmatrelvir/ritonavir 300/100 milligrams (2 × [150/50 milligrams]) combination tablets under fasted conditions (Test 2)

All treatments will be given under fasted conditions. Fasted condition means the participants would not have had anything to eat before taking the medicines.

Around 28 participants will be enrolled in the study. Healthy participants will be tested to see if they can be in the study within 28 days before receiving the study medicine. Selected participants will be admitted to the clinical research unit (CRU) one day before receiving the study medicine and will remain in the CRU until discharge after completing all the treatment periods.

On Day 1 of each period, participants will be given a single dose of study medicine nirmatrelvir/ritonavir 300/100 mg or 150/100 mg by mouth by chance. Study medicine will be given with approximately 240 milliliters of room temperature water under fasted conditions (overnight fast of at least 10 hours and no food until 4 hours after receiving the study medicine). Blood samples will be collected at different times of the day up to 48 hours after taking the study medicine. Participants will be discharged from the CRU on Day 3 of Period 4, after all the study related procedures have been completed.

A follow-up call will be made to participants around 28 to 35 days from receiving the final dose of the study medicine. The study will look at the experiences of participants receiving the study medicine. This will help to understand if the study medicine is safe and effective.

Start Date15 Aug 2025 |

Sponsor / Collaborator |

100 Clinical Results associated with Nirmatrelvir/Ritonavir

Login to view more data

100 Translational Medicine associated with Nirmatrelvir/Ritonavir

Login to view more data

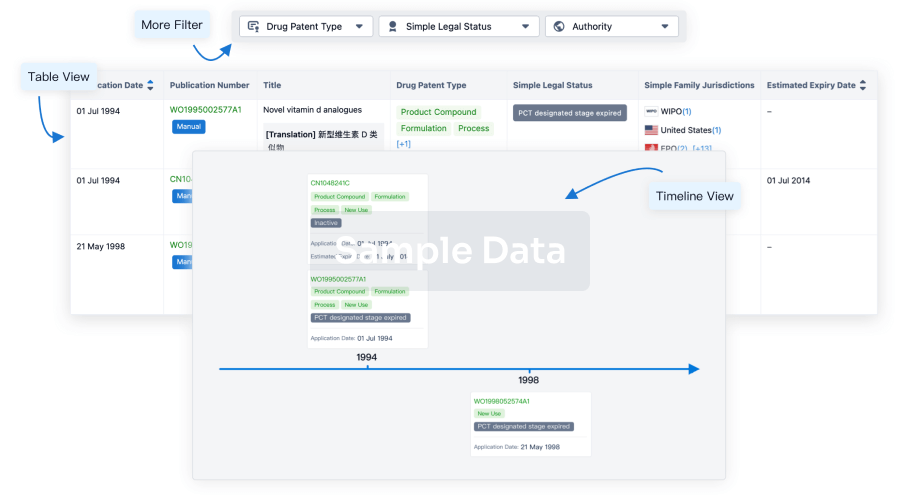

100 Patents (Medical) associated with Nirmatrelvir/Ritonavir

Login to view more data

473

Literatures (Medical) associated with Nirmatrelvir/Ritonavir01 Dec 2025·INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Comparative effectiveness of combination therapy with nirmatrelvir-ritonavir and molnupiravir versus monotherapy with molnupiravir or nirmatrelvir-ritonavir in hospitalized COVID-19 patients: A target trial emulation study

Article

Author: Tam, Anthony Raymond ; Choi, Ming Hong ; Wang, Boyuan ; Hung, Ivan Fan Ngai ; Xu, Yahui ; Wong, Ian Chi Kei ; Yuen, Kwok Yung ; Chan, Esther Wai Yin ; Chu, Wing Ming ; Wan, Eric Yuk Fai

BACKGROUND:

Molnupiravir and nirmatrelvir-ritonavir have demonstrated efficacy in reducing hospitalization and mortality among unvaccinated, high-risk COVID-19 outpatients. However, their impact on hospitalized adults remains unclear. Preclinical studies suggest that combining these antivirals may reduce viral shedding and enhance survival.

METHODS:

This target trial emulation study compared the safety and efficacy of combined molnupiravir and nirmatrelvir-ritonavir versus monotherapy in hospitalized COVID-19 patients in Hong Kong. Data from 28,355 patients aged 18 and older, treated within five days of hospital admission between March 16, 2022, and March 31, 2024, were analyzed. Inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) was used to balance baseline characteristics and outcomes, including mortality, ICU admission, and ventilatory support, which were analyzed using Cox proportional hazards models.

RESULTS:

Nirmatrelvir-ritonavir monotherapy significantly reduced mortality risk (HR: 0.62; 95% CI 0.50-0.77; ARR: -3.16%) compared to combination therapy, with no differences in ICU admission or ventilatory support. It also lowered risks of acute liver injury (HR: 0.53 [95% CI 0.32-0.88]), kidney injury (HR: 0.61 [95% CI 0.51-0.74]), and hyperglycaemia (HR: 0.73 [95% CI 0.57-0.93]).

CONCLUSION:

Combining nirmatrelvir-ritonavir and molnupiravir does not significantly reduce mortality, ICU admissions, or ventilatory support needs in hospitalized COVID-19 adults. Nirmatrelvir-ritonavir monotherapy is more effective, but further randomized controlled trials are required to confirm these findings.

FUNDING:

The Health & Medical Research Fund Commissioned Research on COVID-19 (COVID1903010, COVID1903011; COVID19F01).

01 Nov 2025·DIAGNOSTIC MICROBIOLOGY AND INFECTIOUS DISEASE

The effect of monotherapy versus combination antiviral therapy on all-cause mortality risk in COVID-19 patients

Article

Author: Zhang, Jingfen ; Li, Qiaoyu ; Sun, Yuanyuan ; Shi, Yiwei ; Liu, Jingjing ; Yu, Xiao

This study aimed to determine the effect of Azvudine and Paxlovid on COVID-19 prognosis. A retrospective investigation was conducted on 2,103 hospitalized patients from December 2022 to February 2023 at Shanxi Medical University's First Hospital. Patients were categorized into three groups based on their antiviral treatment: monotherapy, combination therapy, and no treatment. Compared to the control group, both Paxlovid and combination therapy reduced the risk of all-cause mortality (adjusted HR 0.47, 95 % CI 0.27-0.81, P = 0.006 and HR 0.45, 95 % CI 0.24-0.88, P = 0.019, respectively). Subgroup analysis revealed that the association between Azvudine treatment and all-cause mortality risk was significantly stronger in COVID-19 subtypes (interaction P = 0.018), suggesting that the therapeutic effects may be subtype-specific. Therefore, Paxlovid alone reduced mortality risk in moderate and severe cases, while the combination therapy with two antiviral drugs also provided some protection. However, the type-specific impact of Azvudine treatment was notable, with mild cases experiencing significantly better survival rates.

01 Jun 2025·Current Drug Safety

Adverse Events Associated with Antivirals for COVID-19: An Analysis Based on FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS)

Article

Author: Karuppannan, Mahmathi ; Mohamad Radzuan, Muhammad Ikhwan Syahmi

Background::

The COVID-19 pandemic has called for the rapid development and use

of antiviral drugs to effectively control the disease. Nirmatrelvir/Ritonavir (Paxlovid), Molnupiravir, and Remdesivir have been pivotal in therapeutic approaches, although they raise concerns regarding adverse drug reactions (ADRs).

Objective::

This study aimed to thoroughly assess the ADRs associated with these drugs by utilizing the Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) database of the Food and Drug Administration

(FDA)

Methods::

ADR reports for Paxlovid, Molnupiravir, and Remdesivir throughout the period of January 2022 to May 2023 were extracted and classified according to the severity, type of reaction,

and demographic variables. Reporting Odds Ratios (RORs) with 95% confidence intervals were

calculated to evaluate the relationship between antiviral medications and various ADRs.

Results::

The study established notable correlations between Paxlovid and the recurrence of the disease (40.08%) and dysgeusia (16.29%). Molnupiravir was linked to gastrointestinal (16.73%) and

skin reactions (9.47%), while Remdesivir had impairments in the liver (25.21%) and kidneys

(13.34%). ADRs were more commonly observed in female patients treated with Paxlovid

(57.95%) and Molnupiravir (49.40%), whereas Remdesivir ADRs were mostly reported in males

(58.56%). Paxlovid and Remdesivir ADRs were frequently reported in adults between the ages of

18 and 64 (46.01% and 45.01%), while Molnupiravir ADRs were more common in older individuals aged 65 to 85 (40.38%).

Conclusion::

This thorough assessment emphasizes the importance of careful surveillance and control of ADRs linked to COVID-19 antiviral therapies. It is essential to customize treatments by

considering specific patient histories, particularly for pre-existing diseases.

582

News (Medical) associated with Nirmatrelvir/Ritonavir17 Dec 2025

Ratutrelvir shows a differentiated profile versus PAXLOVID™ with fewer adverse events and no viral rebounds Activity shown in Paxlovid®-ineligible patients, representing a significant population with few effective treatment options Final data analysis to be reported in January 2026 NEWTOWN, Pa., Dec. 17, 2025 (GLOBE NEWSWIRE) -- Traws Pharma, Inc. (NASDAQ: TRAW) (“Traws Pharma”, “Traws” or “the Company”), a clinical-stage biopharmaceutical company developing novel therapies to target critical threats to human health from respiratory viral diseases, today announced that interim data with ratutrelvir, an investigational oral, ritonavir-free Mpro/3CL protease inhibitor, demonstrated a differentiated clinical profile in a pre-specified interim analysis of an ongoing randomized, open-label Phase 2 clinical study in patients with mild-to-moderate COVID-19. The study was designed as an active-controlled comparator trial versus PAXLOVID™ (nirmatrelvir/ritonavir) and evaluated patient-reported symptom outcomes, safety, and real-world usability. A separate treatment arm included patients ineligible for ritonavir-boosted regimens due to contraindications or clinically significant drug–drug interactions. To date, 37 patients have been included in the interim analysis, with 25 patients treated with ratutrelvir and 12 patients treated with PAXLOVID™. More than 50% of the planned 90-patient population has been enrolled. Patients in the ratutrelvir arm received ratutrelvir 600 mg orally once daily for 10 days, while patients in the comparator arm received PAXLOVID™ administered as nirmatrelvir 300 mg plus ritonavir 100 mg twice daily for 5 days, consistent with approved prescribing information. “From a clinical perspective, these interim data suggest that ratutrelvir may provide a meaningful benefit across a broader range of patients, including those who are unable to receive ritonavir-boosted therapy,” commented Robert Redfield, MD, Chief Medical Officer, Traws Pharma. “The favorable tolerability profile observed to date, together with the absence of viral rebound events in ratutrelvir-treated patients, is encouraging. While these findings are preliminary and descriptive, they support continued clinical evaluation of ratutrelvir in both acute COVID-19 and in studies designed to better understand its potential impact on longer-term outcomes.” Efficacy Signal Seen in Broad COVID-19-Infected Population Across the interim analysis, ratutrelvir-treated patients demonstrated time-to-sustained symptom alleviation and resolution that was numerically comparable to Paxlovid® -treated patients, as assessed using the FLU-PRO Plus / COVID-19 Symptoms Diary. Sustained alleviation was defined as self-reported alleviation of all COVID-19 symptoms for four consecutive days. At the time of analysis, not all patients had completed the full 28-day observation period, and no formal statistical comparisons were performed; findings are descriptive and non-inferential. No COVID-19 symptom or virologic rebound events have been observed to date in ratutrelvir-treated patients. One rebound event was observed in the PAXLOVID™ comparator arm (1 of 12 patients; 8.3%), occurring shortly after completion of the standard 5-day dosing regimen. Six patients (16.2% of the interim population; 24% of the ratutrelvir cohort) treated with ratutrelvir were ineligible for PAXLOVID™ due to contraindications or drug–drug interaction risk. These patients demonstrated patient-reported symptom improvement dynamics consistent with those observed in the broader ratutrelvir-treated cohort. Favorable Tolerability Profile for Ratutrelvir versus PAXLOVID™ Ratutrelvir was well tolerated in the interim analysis, with fewer reported adverse events compared with the PAXLOVID™-treated cohort. The most commonly reported adverse event among ratutrelvir-treated patients was mild dyspepsia, reported in 2 patients (7.6%). No dysgeusia (a distorted sense of taste) or ritonavir-associated adverse effects were reported, and no treatment discontinuations due to adverse events were observed. In contrast, adverse events commonly associated with PAXLOVID™, including dysgeusia, dizziness, and dyspepsia, were reported in 4 patients (30%) in the comparator arm, consistent with prior clinical trial and real-world experience. Implications for Use of Ratutrelvir for Long-COVID Prevention and Treatment “The combination of early and sustained symptom improvement, extended dosing duration, absence of viral rebound observed to date, and favorable tolerability supports the strategic hypothesis that ratutrelvir may have utility in reducing post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (Long COVID)”, commented Dr. Redfield. “By enabling earlier and potentially more complete viral clearance without the limitations associated with ritonavir boosting, ratutrelvir may offer a differentiated approach to both acute COVID-19 treatment and prevention of longer-term complications, pending confirmation in dedicated clinical studies”. “Collectively, we believe the interim data position ratutrelvir as a next-generation oral 3CL protease inhibitor with ritonavir-free administration, once-daily oral dosing, an improved tolerability profile, applicability to Paxlovid-ineligible populations, and potential relevance to long-COVID prevention strategies,” commented Iain Dukes, MA D Phil, Chief Executive Officer, Traws Pharma. “The study remains ongoing, and completion of enrollment and follow-up will be required to support statistically robust conclusions.” About Ratutrelvir Ratutrelvir is an investigational oral, small molecule Mpro (3CL protease) inhibitor designed to be a broadly acting treatment for SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19 that is used without ritonavir. It has demonstrated in vitro activity against a range of virus strains. Preclinical and Phase 1 studies show that ratutrelvir does not require co-administration with a metabolic inhibitor, such as ritonavir, which could avoid ritonavir-associated drug-drug interactions1, and potentially enable wider patient use. Phase 1 data also showed that ratutrelvir’s pharmacokinetic (PK) profile demonstrated maintenance of target blood plasma levels approximately 13 times above the EC50 using the target Phase 2 dosing regimen of 600 mg/day for ten days, which may reduce the likelihood of clinical rebound and, consequently, reduce the risk for Long COVID2. Industry data indicate that COVID treatment represents a potential multi-billion dollar market opportunity3. Source information: 1.https://ascpt.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/cpt.2646 2.Carly Herbert et al. (2025) Clinical Infectious Diseases. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciae539 3.Pfizer Inc. 10K report 2024, Feb 27, 2025 Third-party products mentioned herein are the trademarks of their respective owners. About Traws Pharma, Inc. Traws Pharma is a clinical stage biopharmaceutical company dedicated to developing novel therapies to target critical threats to human health in respiratory viral diseases. Traws integrates antiviral drug development, medical intelligence and regulatory strategy to meet real world challenges in the treatment of viral diseases. We are advancing novel investigational oral small molecule antiviral agents that have potent activity against difficult to treat or resistant virus strains that threaten human health: COVID-19/Long COVID and bird flu and seasonal influenza. Ratutrelvir is in development as a ritonavir-independent COVID treatment, targeting the Main protease (Mpro or 3CL protease). Tivoxavir marboxil is in development as a single dose treatment for bird flu and seasonal influenza, targeting the influenza cap-dependent endonuclease (CEN). Traws is actively seeking development and commercialization partners for its legacy clinical oncology programs, rigosertib and narazaciclib. More details can be found on Traws’ website at https://www.ir.trawspharma.com/partnering. For more information, please visit www.trawspharma.com and follow us on LinkedIn. Forward-Looking Statements Some of the statements in this release are forward-looking statements within the meaning of Section 27A of the Securities Act of 1933, as amended, Section 21E of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, as amended, and the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995, and involve risks and uncertainties including statements regarding the Company, its business and product candidates, including the potential opportunity, market size, benefits, effectiveness, safety, and the clinical and regulatory plans for ratutrelvir and tivoxavir marboxil, as well as plans for its legacy programs. The Company has attempted to identify forward-looking statements by terminology including “believes”, “estimates”, “anticipates”, “expects”, “plans”, “intends”, “may”, “could”, “might”, “will”, “should”, “potential”, “preliminary”, “encouraging”, “approximately” or other words that convey uncertainty of future events or outcomes. Although Traws believes that the expectations reflected in such forward-looking statements are reasonable as of the date made, expectations may prove to have been materially different from the results expressed or implied by such forward looking statements. These statements are only predictions and involve known and unknown risks, uncertainties, and other factors, including the success and timing of Traws’ clinical trials, including when Traws will report the final data analysis of the Phase 2 studies of ratutrelvir; the potential efficacy of ratutrelvir for the treatment of COVID-19, including for the treatment of PAXLOVID™-ineligible patients; the potential for ratutrelvir to gain market acceptance, if and when regulatory approval is obtained, or become the new standard of care; Traws’ interactions with the FDA, BARDA and similar foreign regulators; collaborations; market conditions; regulatory requirements and pathways for approval; the ongoing need for improved therapy to reduce the frequency of clinical rebound and the concomitant risk for Long COVID; Traws’ ability to raise additional capital when needed; and those discussed under the heading “Risk Factors” in Traws’ filings with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). Any forward-looking statements contained in this release speak only as of its date. Traws undertakes no obligation to update any forward-looking statements contained in this release to reflect events or circumstances occurring after its date or to reflect the occurrence of unanticipated events, except to the extent required by law. Traws Pharma Contact:Charles ParkerTraws Pharma, Inc.cparker@trawspharma.comwww.trawspharma.com Investor Contact:John FrauncesLifeSci Advisors, LLC917-335-2395jfraunces@lifesciadvisors.com

Clinical ResultPhase 2Phase 1

16 Dec 2025

Pfizer is forecasting its 2026 revenue to be in the range of $59.5 billion to $62.5 billion, triggering a 5% decline in its share price.

With COVID sales falling and patent protections expiring, Pfizer is forecasting its 2026 revenue to be in the range of $59.5 billion to $62.5 billion. The midpoint of the projection ($61 billion) would be a decline from this year’s estimated revenue of $62 billion—which the company reaffirmed on Tuesday. It would also be an additional slide from Pfizer’s 2024 revenue of $63.6 billion.Built into the 2026 guidance is a $1.5 billion decline in sales of its COVID products—from an estimated $6.5 billion this year to $5 billion in expected sales next year. The company also expects to sustain a $1.5 billion hit from the loss of exclusivity (LOE) of its products.As those LOEs escalate in the coming years—to $3 billion-plus in 2027 and $6-plus in 2028—the drugmaker said that it doesn’t expect to see growth until 2029.With the updated guidance, Pfizer’s share price fell by 5% by mid-morning on Tuesday.“Once 2028 is behind us, the vast majority of those LOEs are done and the growth drivers that we invest in over the next several years will be maintained and that should allow us to begin to accelerate the top line,” Pfizer chief financial officer Dave Denton said in a conference call. As for its COVID products, Denton said that sales of its antiviral Paxlovid are tumbling at a higher rate than those for its mRNA vaccine.“Paxlovid is more significantly affected as its utilization is directly related to infection rates of the COVID virus,” Denton said. “Comirnaty has shown a slower rate of decline as patients continue to seek protection from COVID via vaccinations despite the narrowing of government eligibility recommendations.”After removing the effects of the LOEs and the COVID products, Pfizer is projecting an approximate 4% increase in operational growth (PDF).In April of this year, Pfizer revealed that it was upping the ante on its cost-cutting efforts, plotting an additional $1.2 billion in reductions largely tied to selling, informational and administrative functions.“We remain on track to deliver about $7.2 billion in total combined net cost savings, with the majority of the savings now expected by the end of 2026 rather than in 2027,” Pfizer CEO Albert Bourla said in the conference call. As for the company’s reliance on its deep vaccine portfolio, Bourla reassured investors that the current threat to sales of its products in the U.S. is an “anomaly.”In the third quarter, Pfizer’s numbers (PDF) were particularly indicative of the erosion in demand for immunizations in the U.S. While sales of its Prevnar franchise of pneumococcal vaccines were up 18% year over year outside of the U.S., they were down 12% domestically. The same was true of Comirnaty, which saw a 9% sales increase internationally and a 25% decline in the U.S.“Vaccines are an essential part of any healthcare system,” Bourla said. “It is the most cost-effective intervention to prevent illness in the world and that will continue. We’re not going away. I can assure you, we are not going back to Louis Pasteur times or before his times.” Bourla added that Pfizer has not altered the way it views its long-term investments on vaccines.“Let’s not forget, the CDC used to be the most reliable and credible organization in the world, that everybody was looking up at,” Bourla said. “I think we need to let the whole thing play [out]. It is an anomaly that will correct itself. It’s mostly driven politically.”

VaccinemRNA

16 Dec 2025

Continued Investment in Pipeline and Acquired Assets in 2026 to Fuel Long-Term Growth

Reaffirms Full-Year 2025 Adjusted (1) Diluted EPS Guidance (2) and Revises Full-Year 2025 Revenue Guidance (2) to Approximately $62.0 Billion

Full-Year 2026 Revenue Guidance (2) Range of $59.5 to $62.5 Billion

Full-Year 2026 Adjusted (1) Diluted EPS Guidance (2) Range of $2.80 to $3.00

NEW YORK--(BUSINESS WIRE)--Pfizer Inc. (NYSE:PFE) today provided its full-year 2026 guidance(2) while revising its November 4, 2025 full-year 2025 Revenue guidance(2) and reaffirming all other components of full-year 2025 financial guidance(2). The accompanying presentation can be found at www.pfizer.com/investors.

FULL-YEAR 2026 REVENUE GUIDANCE(2)

Pfizer anticipates full-year 2026 revenues to be in the range of $59.5 to $62.5 billion, while full-year 2025 revenue guidance(2) is revised to approximately $62.0 billion from the range of $61.0 to $64.0 billion previously. Full-year 2026 revenue guidance(2) includes the expectation of revenues from our COVID-19 products being approximately $1.5 billion lower than what is expected in 2025 plus an expected year-over-year negative revenue impact of approximately $1.5 billion due to certain products experiencing loss of exclusivity (LOE)(2). Pfizer expects full-year 2026 operational(3) revenue growth at the midpoint, excluding both COVID-19 and LOE products, to be approximately 4% year-over-year.

FULL-YEAR 2026 ADJUSTED(1) SI&A and ADJUSTED(1) R&D EXPENSES GUIDANCE(2)

Pfizer anticipates full-year 2026 Adjusted(1) SI&A expenses to be in the range of $12.5 to $13.5 billion, reflecting ongoing progress with our Cost Realignment Program. The company anticipates full-year 2026 Adjusted(1) R&D expenses to be in the range of $10.5 to $11.5 billion, reflecting continued focus on prioritization in key therapeutic areas and maximizing the development of PF-08634404 (a PD-1 x VEGF bispecific antibody in-licensed from 3SBio) as well as multiple clinical programs from Metsera. Consequently, total 2026 Adjusted(1) SI&A and R&D expenses are expected to be in the range of $23.0 to $25.0 billion.

FULL-YEAR 2026 ADJUSTED(1) DILUTED EPS GUIDANCE(2)

Pfizer anticipates full-year 2026 Adjusted(1) diluted EPS to be in a range of $2.80 to $3.00. 2026 Adjusted(1) diluted EPS guidance(2) primarily reflects our expected revenues, anticipated stable gross and operating margins vs full-year 2025 guidance(2), and an anticipated higher tax rate on Adjusted(1) income vs full-year 2025 guidance(2).

A comparison of Pfizer’s 2025 Financial Guidance(2) to its 2026 Financial Guidance(2) is presented below.

2025 Financial Guidance(2)

(as of December 16, 2025)

2026 Financial Guidance(2)

Revenues ($ in billions)

Approximately $62.0

(previously $61.0 – $64.0)

$59.5 – $62.5

COVID-19 Products ($ in billions)

~$6.5

~$5.0

Adjusted(1) SI&A Expenses ($ in billions)

$13.1 – $14.1

$12.5 – $13.5

Adjusted(1) R&D Expenses ($ in billions)

$10.0 – $11.0

$10.5 – $11.5

Effective Tax Rate on Adjusted(1) Income

Approximately 11%

Approximately 15%

Adjusted(1) Diluted EPS

$3.00 – $3.15

$2.80 – $3.00

Financial guidance for Adjusted(1) diluted EPS is calculated using approximately 5.71 billion weighted-average shares outstanding in 2025 and approximately 5.74 billion weighted-average shares outstanding in 2026, and assumes no share repurchases in 2025 or 2026.

CEO COMMENTARY

“2025 was a year of strong execution and strategic progress for Pfizer. We’ve strengthened our foundation, advanced our R&D pipeline and positioned our company for sustainable growth in the post-LOE period. As we move into 2026, we’re focused on serving patients with innovative medicines and vaccines while creating long-term value for our shareholders.”

PFIZER TO HOST CONFERENCE CALL

Pfizer will host a live conference call and webcast today, December 16, 2025, at 8:00 AM EST. To access the live conference call as well as view the Full-Year 2026 Financial Guidance presentation, visit our website at pfizer.com/investors.

You can also listen to the conference call by dialing either 800-456-4352 in the U.S. and Canada or 785-424-1086 outside of the U.S. and Canada. The passcode is “71848”.

The transcript and webcast replay of the call will be made available on our website at pfizer.com/investors within 24 hours after the end of the live conference call and will be accessible for at least 90 days.

(1)

Adjusted income and Adjusted diluted earnings per share (EPS) are defined as U.S. GAAP net income attributable to Pfizer Inc. common shareholders and U.S. GAAP diluted EPS attributable to Pfizer Inc. common shareholders before the impact of amortization of intangible assets, certain acquisition-related items, discontinued operations, and certain significant items. Adjusted income and its components and Adjusted diluted EPS measures are not, and should not be viewed as, substitutes for U.S. GAAP net income and its components and diluted EPS(4), have no standardized meaning prescribed by U.S. GAAP and may not be comparable to the calculation of similar measures of other companies. See the Non-GAAP Financial Measure: Adjusted Income section of Management’s Discussion and Analysis of Financial Condition and Results of Operations in Pfizer’s 2024 Annual Report on Form 10-K for a definition of each component of Adjusted income as well as other relevant information.

(2)

Pfizer does not provide guidance for U.S. generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) Reported financial measures (other than revenues) or a reconciliation of forward-looking non-GAAP financial measures to the most directly comparable GAAP Reported financial measures on a forward-looking basis because it is unable to predict with reasonable certainty the ultimate outcome of unusual gains and losses, certain acquisition-related expenses, gains and losses from equity securities, actuarial gains and losses from pension and postretirement plan remeasurements, potential future asset impairments and pending litigation without unreasonable effort. These items are uncertain, depend on various factors, and could have a material impact on U.S. GAAP Reported results for the guidance period.

Financial guidance for full-year 2026 reflects the following:

Our financial guidance for full-year 2025 reflects assumptions that are consistent with those outlined in Note (1) within Pfizer’s Q3-25 Earnings Release.

(3)

References to operational variances in this press release pertain to period-over-period changes that exclude the impact of foreign exchange rates. Although exchange rate changes are part of Pfizer’s business, they are not within Pfizer’s control and because they can mask positive or negative trends in the business, Pfizer believes presenting operational variances excluding these foreign exchange changes provides useful information to evaluate Pfizer’s results.

(4)

Revenues is defined as revenues in accordance with U.S. GAAP. Reported net income and its components are defined as net income attributable to Pfizer Inc. common shareholders and its components in accordance with U.S. GAAP. Reported diluted EPS is defined as diluted EPS attributable to Pfizer Inc. common shareholders in accordance with U.S. GAAP.

DISCLOSURE NOTICE: The information contained in this press release is as of December 16, 2025. Pfizer assumes no obligation to update forward-looking statements contained in this release or the webcast as the result of new information or future events or developments.

This press release and the webcast contain or may contain forward-looking information about, among other topics, our anticipated operating and financial performance, including financial guidance and projections; reorganizations; business plans, strategy, goals and prospects; expectations for our product pipeline (including products from completed or anticipated acquisitions), in-line products and product candidates, including anticipated regulatory submissions, data read-outs, study starts, approvals, launches, discontinuations, clinical trial results and other developing data, revenue contribution and projections, pricing and reimbursement, market dynamics, including demand, market size and utilization rates and growth, performance, timing and duration of exclusivity and potential benefits; the impact and potential impact of tariffs and pricing dynamics; strategic reviews; leverage and capital allocation objectives; an enterprise-wide cost realignment program (including anticipated costs, savings and potential benefits); a Manufacturing Optimization Program to reduce our cost of goods sold (including anticipated costs, savings and potential benefits); dividends and share repurchases; plans for and prospects of our acquisitions, dispositions and other business development activities, including our acquisition of Seagen, our acquisition of Metsera and our licensing agreement with 3SBio, and our ability to successfully capitalize on growth opportunities and prospects; our voluntary agreement with the U.S. Government designed to lower drug costs for U.S. patients and to include Pfizer products in a direct purchasing platform, and Pfizer’s plans to further invest in U.S. manufacturing; manufacturing and product supply; our ongoing efforts to respond to COVID-19; our expectations regarding the impact of COVID-19 on our business, operations and financial results; and the expected seasonality of demand for certain of our products. Given their forward-looking nature, these statements involve substantial risks, uncertainties and potentially inaccurate assumptions and we cannot assure you that any outcome expressed in these forward-looking statements will be realized in whole or in part. You can identify these statements by the fact that they use future dates or use words such as “will,” “may,” “could,” “likely,” “ongoing,” “anticipate,” “estimate,” “expect,” “project,” “intend,” “plan,” “believe,” “assume,” “target,” “forecast,” “guidance,” “goal,” “objective,” “aim,” “seek,” “potential,” “hope” and other words and terms of similar meaning. Pfizer’s financial guidance is based on estimates and assumptions that are subject to significant uncertainties.

Among the factors that could cause actual results to differ materially from past results and future plans and projected future results are the following:

Risks Related to Our Business, Industry and Operations, and Business Development:

the outcome of research and development (R&D) activities, including the ability to meet anticipated pre-clinical or clinical endpoints, commencement and/or completion dates for our pre-clinical or clinical trials, regulatory submission dates, and/or regulatory approval and/or launch dates; the possibility of unfavorable pre-clinical and clinical trial results, including the possibility of unfavorable new pre-clinical or clinical data and further analyses of existing pre-clinical or clinical data; risks associated with preliminary, early stage or interim data; the risk that pre-clinical and clinical trial data are subject to differing interpretations and assessments, including during the peer review/publication process, in the scientific community generally, and by regulatory authorities; whether and when additional data from our pipeline programs will be published in scientific journal publications and, if so, when and with what modifications and interpretations; and uncertainties regarding the future development of our product candidates, including whether or when our product candidates will advance to future studies or phases of development or whether or when regulatory applications may be filed for any of our product candidates, including as a result of clinical trial data or regulatory feedback that could impact the future development of our product candidates, including our vaccine candidates such as our next generation pneumococcal conjugate vaccine candidate;

our ability to successfully address comments received from regulatory authorities such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration or the European Medicines Agency, or obtain approval for new products and indications from regulators on a timely basis or at all;

regulatory decisions impacting labeling, approval or authorization, including the scope of indicated patient populations, product dosage, manufacturing processes, safety and/or other matters, including decisions relating to emerging developments regarding potential product impurities; uncertainties regarding the ability to obtain or maintain, and the scope of, recommendations by technical or advisory committees, and the timing of, and ability to obtain, pricing approvals and product launches, all of which could impact the availability or commercial potential of our products and product candidates;

claims and concerns that may arise regarding the safety or efficacy of in-line products and product candidates, including claims and concerns that may arise from the conduct or outcome of post-approval clinical trials, pharmacovigilance or Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies, which could impact marketing approval, product labeling, and/or availability or commercial potential;

the success and impact of external business development activities, such as the November 2025 acquisition of Metsera, including the ability to identify and execute on potential business development opportunities; the ability to satisfy the conditions to closing of announced transactions in the anticipated time frame or at all, including the possibility that such transactions do not close; the ability to realize the anticipated benefits of any such transactions in the anticipated time frame or at all; the potential need for and impact of additional equity or debt financing to pursue these opportunities, which has in the past and could in the future result in increased leverage and/or a downgrade of our credit ratings and could limit our ability to obtain future financing; challenges integrating the businesses and operations; disruption to business or operations relationships; risks related to growing revenues for certain acquired or partnered products; significant transaction costs; and unknown liabilities;

competition, including from new product entrants, in-line branded products, generic products, private label products, biosimilars and product candidates that treat or prevent diseases and conditions similar to those treated or intended to be prevented by our in-line products and product candidates;

the ability to successfully market both new and existing products, including biosimilars;

difficulties or delays in manufacturing, sales or marketing; supply disruptions, shortages or stock-outs at our facilities or third-party facilities that we rely on; and legal or regulatory actions;

the impact of public health outbreaks, epidemics or pandemics (such as COVID-19) on our business, operations and financial condition and results, including impacts on our employees, manufacturing, supply chain, sales and marketing, R&D and clinical trials;

risks and uncertainties related to Comirnaty and Paxlovid or any potential future COVID-19 vaccines, treatments or combinations, including, among others, the risk that as the market for COVID-19 products remains endemic and seasonal and/or COVID-19 infection rates do not follow prior patterns, demand for our COVID-19 products has and may continue to be reduced or not meet expectations, which has in the past and may continue to lead to reduced revenues, excess inventory or other unanticipated charges; risks related to our ability to develop, receive regulatory approval for, and commercialize variant adapted vaccines, combinations and/or treatments; uncertainties related to recommendations and coverage for, and the public’s adherence to, vaccines, boosters, treatments or combinations, including uncertainties related to the potential impact of narrowing recommended patient populations; whether or when our EUAs or biologics licenses will expire, terminate or be revoked; risks related to our ability to accurately predict or achieve our revenue forecasts for Comirnaty and Paxlovid or any potential future COVID-19 vaccines or treatments; and potential third-party royalties or other claims related to Comirnaty and Paxlovid;

trends toward managed care and healthcare cost containment, and our ability to obtain or maintain timely or adequate pricing or favorable formulary placement for our products;

interest rate and foreign currency exchange rate fluctuations, including the impact of global trade tensions, as well as currency devaluations and monetary policy actions in countries experiencing high inflation or deflation rates;

any significant issues involving our largest wholesale distributors or government customers, which account for a substantial portion of our revenues;

the impact of the increased presence of counterfeit medicines, vaccines or other products in the pharmaceutical supply chain;

any significant issues related to the outsourcing of certain operational and staff functions to third parties;

any significant issues related to our JVs and other third-party business arrangements, including modifications or disputes related to supply agreements or other contracts with customers including governments or other payors;

uncertainties related to general economic, political, business, industry, regulatory and market conditions including, without limitation, uncertainties related to the impact on us, our customers, suppliers and lenders and counterparties to our foreign-exchange and interest-rate agreements of challenging global economic conditions, such as inflation or interest rate fluctuations, and recent and possible future changes in global financial markets;

the exposure of our operations globally to possible capital and exchange controls, economic conditions, expropriation, sanctions, tariffs and/or other restrictive government actions, changes in intellectual property legal protections and remedies, unstable governments and legal systems and inter-governmental disputes;

risks and uncertainties related to issued or future executive orders or other new, or changes in, laws, regulations or policy regarding tariffs or other trade policy and/or the impact of any potential U.S. Governmental shutdowns, including impacts on governmental agencies due to a shutdown;

the risk and impact of tariffs on our business, which is subject to a number of factors including, but not limited to, restrictions on trade, the effective date and duration of such tariffs, countries included in the scope of tariffs, changes to amounts of tariffs, and potential retaliatory tariffs or other retaliatory actions imposed by other countries;

the impact of disruptions related to climate change and natural disasters;

any changes in business, political and economic conditions due to actual or threatened terrorist activity, geopolitical instability, political or civil unrest or military action, including the ongoing conflicts between Russia and Ukraine and in the Middle East and the resulting economic or other consequences;

the impact of product recalls, withdrawals and other unusual items, including uncertainties related to regulator-directed risk evaluations and assessments, such as our ongoing evaluation of our product portfolio for the potential presence or formation of nitrosamines, and our voluntary withdrawal of all lots of Oxbryta in all markets where it is approved and any regulatory or other impact on Oxbryta and other sickle cell disease assets;

trade buying patterns;

the risk of an impairment charge related to our intangible assets, goodwill or equity-method investments;

the impact of, and risks and uncertainties related to, restructurings and internal reorganizations, as well as any other corporate strategic initiatives and growth strategies, and cost-reduction and productivity initiatives, including any potential future phases, each of which requires upfront costs but may fail to yield anticipated benefits and may result in unexpected costs, organizational disruption, adverse effects on employee morale, retention issues or other unintended consequences;

the ability to successfully achieve our climate-related goals and progress our environmental sustainability and other priorities;

Risks Related to Government Regulation and Legal Proceedings:

the impact of any U.S. healthcare reform or legislation, including executive orders or other change in laws, regulations or policy, or any significant spending reduction or cost control efforts affecting Medicare, Medicaid, the 340B Drug Pricing Program or other publicly funded or subsidized health programs, including the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 (IRA) and the IRA Medicare Part D Redesign, or changes in the tax treatment of employer-sponsored health insurance that may be implemented;

risks and uncertainties related to the impact of Pfizer’s voluntary agreement with the U.S. Government designed to lower drug costs for U.S. patients and to include Pfizer products in a direct purchasing platform, and Pfizer’s plans to further invest in U.S. manufacturing, including risks relating to entering into definitive agreements with the U.S. Government and the initiation of new tariffs not subject to Pfizer’s grace period;

U.S. federal or state legislation or regulatory action and/or policy efforts affecting, among other things, pharmaceutical product pricing, including international reference pricing, including Most-Favored-Nation drug pricing, intellectual property, reimbursement or access to or recommendations for our medicines and vaccines, tax changes or other restrictions on U.S. direct-to-consumer advertising; limitations on interactions with healthcare professionals and other industry stakeholders; as well as pricing pressures for our products as a result of highly competitive biopharmaceutical markets;

risks and uncertainties related to changes to vaccine or other healthcare policy in the U.S., including the U.S. Food and Drug Administration's recently adopted policy of disclosing Complete Response Letters for unapproved drug candidates and the attendant risk of disclosure of trade secrets or confidential commercial information;

legislation or regulatory action in markets outside of the U.S., such as China or Europe, including, without limitation, laws related to pharmaceutical product pricing, intellectual property, medical regulation, environmental protections, data protection and cybersecurity, reimbursement or access, including, in particular, continued government-mandated reductions in prices and access restrictions for certain products to control costs in those markets;

legal defense costs, insurance expenses, settlement costs and contingencies, including without limitation, those related to legal proceedings and actual or alleged environmental contamination;

the risk and impact of an adverse decision or settlement and risk related to the adequacy of reserves related to legal proceedings;

the risk and impact of tax related litigation and investigations;

governmental laws, regulations and policies affecting our operations, including, without limitation, the IRA, as well as changes in such laws, regulations or policies or their interpretation, including, among others, new or changes in tariffs, tax laws and regulations internationally and in the U.S., including the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, which was enacted on July 4, 2025, and is still subject to further guidance; the adoption of global minimum taxation requirements outside the U.S. generally effective in most jurisdictions since January 1, 2024, government cost-cutting measures and related impacts on, among other matters, government staffing, resources and ability to timely review and process regulatory or other submissions; restrictions related to certain data transfers and transactions involving certain countries; and potential changes to existing tax laws, tariffs, or changes to other laws, regulations or policies in the U.S., including by the U.S. Presidential administration and Congress, as well as in other countries;

Risks Related to Intellectual Property, Technology and Cybersecurity:

the risk that our currently pending or future patent applications may not be granted on a timely basis or at all, or any patent-term extensions that we seek may not be granted on a timely basis, if at all;

risks to our products, patents and other intellectual property, such as: (i) claims of invalidity that could result in loss of patent coverage; (ii) claims of patent infringement, including asserted and/or unasserted intellectual property claims; (iii) claims we may assert against intellectual property rights held by third parties; (iv) challenges faced by our collaboration or licensing partners to the validity of their patent rights; or (v) any pressure from, or legal or regulatory action by, various stakeholders or governments that could potentially result in us not seeking intellectual property protection or agreeing not to enforce or being restricted from enforcing intellectual property rights related to our products;

any significant breakdown or interruption of our information technology systems and infrastructure (including cloud services);

any business disruption, theft of confidential or proprietary information, security threats on facilities or infrastructure, extortion or integrity compromise resulting from a cyber-attack, which may include those using adversarial artificial intelligence techniques, or other malfeasance by, but not limited to, nation states, employees, business partners or others; and

risks and challenges related to the use of software and services that include artificial intelligence-based functionality and other emerging technologies.

Should known or unknown risks or uncertainties materialize or should underlying assumptions prove inaccurate, actual results could vary materially from past results and those anticipated, estimated or projected. Investors are cautioned not to put undue reliance on forward-looking statements. A further list and description of risks, uncertainties and other matters can be found in our Annual Report on Form 10-K for the fiscal year ended December 31, 2024 and in our subsequent reports on Form 10-Q, in each case including in the sections thereof captioned “Forward-Looking Information and Factors That May Affect Future Results” and “Item 1A. Risk Factors,” and in our subsequent reports on Form 8-K, all of which are filed with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission and available at www.sec.gov and www.pfizer.com.

Financial StatementVaccineAcquisition

100 Deals associated with Nirmatrelvir/Ritonavir

Login to view more data

R&D Status

Approved

10 top approved records. to view more data

Login

| Indication | Country/Location | Organization | Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 | South Korea | 27 Dec 2021 |

Developing

10 top R&D records. to view more data

Login

| Indication | Highest Phase | Country/Location | Organization | Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post Acute COVID 19 Syndrome | Phase 2 | Sweden | 01 May 2023 |

Login to view more data

Clinical Result

Clinical Result

Indication

Phase

Evaluation

View All Results

| Study | Phase | Population | Analyzed Enrollment | Group | Results | Evaluation | Publication Date |

|---|

Phase 2 | 963 | (Experimental: Paxlovid 25 Day Dosing) | caoftjumcg = pcfprguuqz yspvitlzhu (onhhkytjjv, ihlkdcykhr - afjrhbsyyg) View more | - | 02 Dec 2025 | ||

(Experimental: Paxlovid 15 Day Dosing) | caoftjumcg = kvzcaezmuu yspvitlzhu (onhhkytjjv, ltdchoanqr - rdmkmfydjp) View more | ||||||

GlobeNewswire Manual | Not Applicable | 27 | bvfqkgacxu(ekzbgrhyem): P-Value = <0.0001 View more | Positive | 04 Sep 2025 | ||

Phase 2/3 | 2,113 | Nirmatrelvir/Ritonavir (NMV/R) 300 mg/100 mg | tzhyjbyhkv(wzeiaoxxry) = wbwvnzhawx lyvtjghept (kcjqguqyuc ) View more | Positive | 11 Nov 2024 | ||

Placebo | tzhyjbyhkv(wzeiaoxxry) = ggnoetavys lyvtjghept (kcjqguqyuc ) View more | ||||||

Phase 1 | 12 | (Period 1: Rosuvastatin 10 mg) | gahxmpgezm(dyxkzwnzxv) = iiecoumuqp hxshneftul (gyjnrjxrlq, 46) View more | - | 28 Oct 2024 | ||

Rosuvastatin+Nirmatrelvir+Ritonavir (Period 2: Rosuvastatin 10 mg + Nirmatrelvir 300 mg/ Ritonavir 100 mg) | gahxmpgezm(dyxkzwnzxv) = mvgyxyjvvo hxshneftul (gyjnrjxrlq, 48) View more | ||||||

Phase 1 | - | 14 | PF-07321332+Ritonavir | oqduaeclmz(zboqdgxanh) = jkuhheibdb qblczrkpcd (jwuhzvawor, 29) View more | - | 08 Oct 2024 | |

Phase 1 | - | 15 | Nirmatrelvir+Ritonavir (Nirmatrelvir/Ritonavir 300(2*150)/100 mg) | bpciksoqbu(xcikzeegac) = umbkdmpmvy dkpvuzpgbv (osptwtvqni, 36) View more | - | 19 Sep 2024 | |

Nirmatrelvir+Ritonavir (Nirmatrelvir/Ritonavir 2*(150/50 mg) Low Disintegrant) | bpciksoqbu(xcikzeegac) = vncyolifrp dkpvuzpgbv (osptwtvqni, 28) View more | ||||||

Phase 1 | - | 12 | Nirmatrelvir+Ritonavir (Nirmatrelvir/Ritonavir 300/100 mg Commercial Tablets) | tufnsgreqg(gmrosavgwl) = xulbspzovb yqtacwmzcd (yraqdjnpga, 36) View more | - | 06 Jun 2024 | |

Nirmatrelvir+Ritonavir (Nirmatrelvir/Ritonavir 300/100 mg Oral Powder Mixed With Water) | tufnsgreqg(gmrosavgwl) = ofxnxlxliy yqtacwmzcd (yraqdjnpga, 25) View more | ||||||

ASCO2024 Manual | Not Applicable | 182 | iweqzkeskj(wlozoaovvs) = bizanpmgbd dusofwiljf (xngwfxiivj ) View more | Positive | 24 May 2024 | ||

Phase 1 | - | 12 | Nirmatrelvir+Ritonavir (Nirmatrelvir/Ritonavir 300/100 mg Tablets (Fasted)) | ekgdoczkym(maleafyifm) = wsozuaaqxk ltkhzuwyam (awxngznhlx, 18) View more | - | 10 May 2024 | |

Nirmatrelvir+Ritonavir (Nirmatrelvir/Ritonavir 300/100 mg Oral Powder Mixed With Water (Fasted)) | ekgdoczkym(maleafyifm) = ayfwpsapou ltkhzuwyam (awxngznhlx, 22) View more | ||||||

Phase 1 | - | 24 | (Treatment 1: Dabigatran 75 mg) | prpfjmccsw(alubxcivip) = ckuziwapqp qdubyzigai (bhflazxhaa, 78) View more | - | 29 Mar 2024 | |

(Treatment 2: PF-07321332 300 mg + Ritonavir 100 mg + Dabigatran 75 mg) | prpfjmccsw(alubxcivip) = mfmvfqhyvb qdubyzigai (bhflazxhaa, 72) View more |

Login to view more data

Translational Medicine

Boost your research with our translational medicine data.

login

or

Deal

Boost your decision using our deal data.

login

or

Core Patent

Boost your research with our Core Patent data.

login

or

Clinical Trial

Identify the latest clinical trials across global registries.

login

or

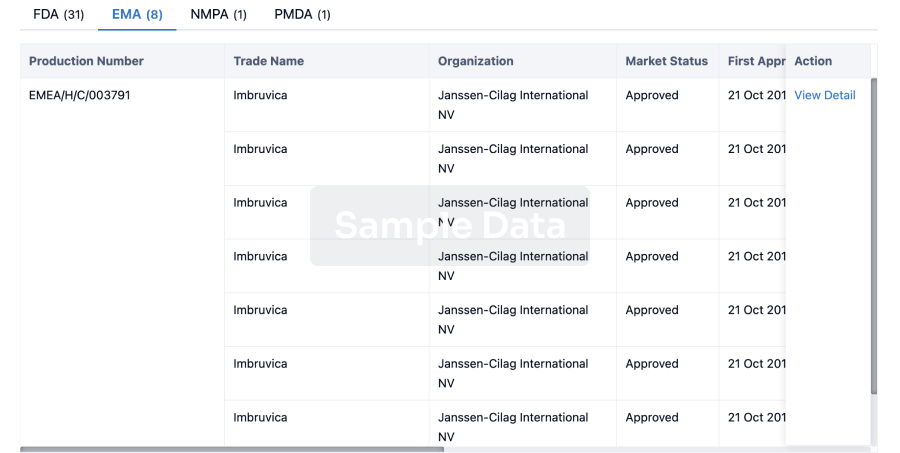

Approval

Accelerate your research with the latest regulatory approval information.

login

or

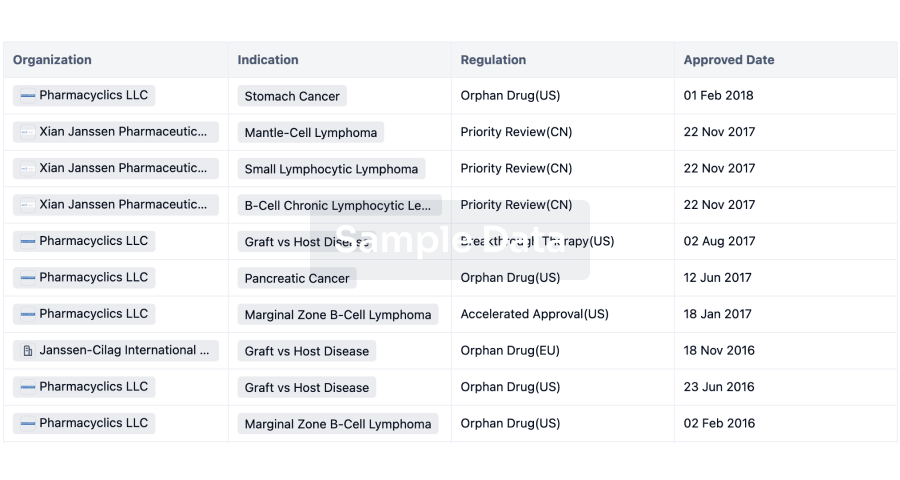

Regulation

Understand key drug designations in just a few clicks with Synapse.

login

or

AI Agents Built for Biopharma Breakthroughs

Accelerate discovery. Empower decisions. Transform outcomes.

Get started for free today!

Accelerate Strategic R&D decision making with Synapse, PatSnap’s AI-powered Connected Innovation Intelligence Platform Built for Life Sciences Professionals.

Start your data trial now!

Synapse data is also accessible to external entities via APIs or data packages. Empower better decisions with the latest in pharmaceutical intelligence.

Bio

Bio Sequences Search & Analysis

Sign up for free

Chemical

Chemical Structures Search & Analysis

Sign up for free