Request Demo

What is Niacin used for?

15 June 2024

Niacin, also known as Vitamin B3, is a vital nutrient that comes in two primary forms: nicotinic acid and niacinamide (also known as nicotinamide). It is available under several drug trade names, including Niaspan and Niacor. This nutrient targets various metabolic processes and has significant implications in cardiovascular health. Research institutions worldwide are continually exploring niacin's potential to treat a range of conditions, including high cholesterol, pellagra, and even skin conditions such as acne. As a drug, niacin is classified under water-soluble vitamins and is essential for the human body to convert food into energy. It's also a common ingredient in multivitamins and B-complex supplements.

Niacin's indications cover a broad spectrum, with the most well-known being its use in treating dyslipidemia by lowering bad cholesterol (LDL) and triglycerides while raising good cholesterol (HDL). This has led to its widespread adoption in cardiovascular health management. Pellagra, a disease caused by niacin deficiency, is another condition effectively treated by this nutrient. Recent research is also investigating its potential in managing metabolic disorders, neurodegenerative diseases, and even as an adjunct therapy in cancer treatments. While niacin has demonstrated significant benefits in these areas, ongoing clinical trials and studies continue to explore its full therapeutic potential.

Niacin Mechanism of Action

The mechanism of action of niacin, particularly in its role of managing cholesterol levels, involves complex biochemical processes. Once ingested, niacin is converted into nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADP), both essential coenzymes in the body. These coenzymes are involved in the redox reactions necessary for cellular metabolism. In its lipid-altering role, niacin primarily works by inhibiting the enzyme diacylglycerol acyltransferase-2 (DGAT2), which is involved in the synthesis of triglycerides. By inhibiting this enzyme, niacin reduces the production of very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) in the liver, which in turn decreases LDL levels in the bloodstream.

Furthermore, niacin enhances HDL levels by reducing the clearance of apolipoprotein A-I, a major component of HDL, thus promoting reverse cholesterol transport. This dual action of lowering LDL and raising HDL makes niacin particularly effective in managing dyslipidemia. Additionally, niacin has been shown to possess anti-inflammatory properties, which can contribute to its cardiovascular benefits by reducing inflammation in the arterial walls. Overall, these mechanisms collectively contribute to niacin's efficacy in improving lipid profiles and supporting cardiovascular health.

How to Use Niacin

Niacin is available in several forms, including immediate-release, extended-release, and sustained-release formulations. The method of administration depends on the specific condition being treated and the formulation of the niacin being used. For managing cholesterol levels, extended-release formulations such as Niaspan are commonly prescribed due to their reduced risk of side effects compared to immediate-release forms. These are usually taken orally, once a day, preferably at bedtime after a low-fat snack to minimize stomach upset and the risk of flushing, a common side effect.

The onset of action for niacin in altering lipid levels can vary, but noticeable changes in cholesterol levels can often be seen within a few weeks of consistent use. However, it may take several months to achieve the full therapeutic effect. When treating pellagra, a condition caused by severe niacin deficiency, immediate-release formulations may be used, administered multiple times a day to quickly replenish the body's niacin levels. The dosage and frequency depend on the severity of the deficiency and the patient's response to treatment.

Patients are typically advised to start with a lower dose and gradually increase it to minimize side effects. It's crucial to follow the prescribed dosage and not to discontinue use abruptly, as this can lead to a rebound effect, particularly with extended-release formulations. Regular monitoring by a healthcare provider is essential to adjust the dosage as needed and to check for any adverse effects.

What is Niacin Side Effects

While niacin is generally safe when taken as prescribed, it can cause a range of side effects. The most common is flushing, which involves redness, warmth, itching, or tingling of the skin, usually on the face and neck. This side effect is more common with immediate-release formulations and can often be mitigated by taking aspirin 30 minutes before the niacin dose or by using extended-release formulations. Other common side effects include gastrointestinal issues such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.

More serious but less common side effects include liver toxicity, which can manifest as elevated liver enzymes in blood tests, jaundice, or other signs of liver dysfunction. Regular liver function tests are recommended for patients on long-term niacin therapy. High doses of niacin can also increase blood sugar levels, which is particularly concerning for diabetic patients. Therefore, blood glucose levels should be closely monitored.

Contraindications for niacin use include known hypersensitivity to niacin or any of its components, active liver disease, peptic ulcer disease, and arterial bleeding. Pregnant and breastfeeding women should consult their healthcare provider before starting niacin, as high doses may not be safe during pregnancy and lactation. Patients with a history of gout or gallbladder disease should use niacin with caution, as it can exacerbate these conditions.

What Other Drugs Will Affect Niacin

Several medications can interact with niacin, potentially altering its efficacy or increasing the risk of side effects. Statins, commonly prescribed alongside niacin for dyslipidemia, can increase the risk of myopathy or rhabdomyolysis, a severe form of muscle damage. Therefore, patients taking both niacin and statins should be closely monitored for muscle pain or weakness.

Blood pressure medications, particularly vasodilators and alpha-blockers, can enhance the blood pressure-lowering effects of niacin, potentially leading to hypotension. It's essential to monitor blood pressure regularly and adjust dosages as necessary under medical supervision.

Anticoagulants and antiplatelet drugs, such as warfarin and aspirin, can also interact with niacin, increasing the risk of bleeding. Patients on these medications should be monitored for signs of unusual bleeding or bruising, and regular blood tests may be required to ensure safe use.

Medications for diabetes can be affected by niacin's potential to raise blood sugar levels. Insulin and oral hypoglycemic agents may require dosage adjustments to maintain optimal blood glucose control. Additionally, bile acid sequestrants, used to lower cholesterol, can interfere with niacin absorption if taken simultaneously. To avoid this, niacin should be taken either one hour before or four to six hours after bile acid sequestrants.

In conclusion, niacin is a versatile and essential nutrient with significant therapeutic potential, particularly in managing lipid disorders and preventing cardiovascular diseases. Understanding its mechanisms, proper usage, potential side effects, and drug interactions is crucial for maximizing its benefits while minimizing risks. Regular consultations with healthcare providers are essential to ensure safe and effective use of niacin, tailored to individual health needs and conditions.

Niacin's indications cover a broad spectrum, with the most well-known being its use in treating dyslipidemia by lowering bad cholesterol (LDL) and triglycerides while raising good cholesterol (HDL). This has led to its widespread adoption in cardiovascular health management. Pellagra, a disease caused by niacin deficiency, is another condition effectively treated by this nutrient. Recent research is also investigating its potential in managing metabolic disorders, neurodegenerative diseases, and even as an adjunct therapy in cancer treatments. While niacin has demonstrated significant benefits in these areas, ongoing clinical trials and studies continue to explore its full therapeutic potential.

Niacin Mechanism of Action

The mechanism of action of niacin, particularly in its role of managing cholesterol levels, involves complex biochemical processes. Once ingested, niacin is converted into nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADP), both essential coenzymes in the body. These coenzymes are involved in the redox reactions necessary for cellular metabolism. In its lipid-altering role, niacin primarily works by inhibiting the enzyme diacylglycerol acyltransferase-2 (DGAT2), which is involved in the synthesis of triglycerides. By inhibiting this enzyme, niacin reduces the production of very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) in the liver, which in turn decreases LDL levels in the bloodstream.

Furthermore, niacin enhances HDL levels by reducing the clearance of apolipoprotein A-I, a major component of HDL, thus promoting reverse cholesterol transport. This dual action of lowering LDL and raising HDL makes niacin particularly effective in managing dyslipidemia. Additionally, niacin has been shown to possess anti-inflammatory properties, which can contribute to its cardiovascular benefits by reducing inflammation in the arterial walls. Overall, these mechanisms collectively contribute to niacin's efficacy in improving lipid profiles and supporting cardiovascular health.

How to Use Niacin

Niacin is available in several forms, including immediate-release, extended-release, and sustained-release formulations. The method of administration depends on the specific condition being treated and the formulation of the niacin being used. For managing cholesterol levels, extended-release formulations such as Niaspan are commonly prescribed due to their reduced risk of side effects compared to immediate-release forms. These are usually taken orally, once a day, preferably at bedtime after a low-fat snack to minimize stomach upset and the risk of flushing, a common side effect.

The onset of action for niacin in altering lipid levels can vary, but noticeable changes in cholesterol levels can often be seen within a few weeks of consistent use. However, it may take several months to achieve the full therapeutic effect. When treating pellagra, a condition caused by severe niacin deficiency, immediate-release formulations may be used, administered multiple times a day to quickly replenish the body's niacin levels. The dosage and frequency depend on the severity of the deficiency and the patient's response to treatment.

Patients are typically advised to start with a lower dose and gradually increase it to minimize side effects. It's crucial to follow the prescribed dosage and not to discontinue use abruptly, as this can lead to a rebound effect, particularly with extended-release formulations. Regular monitoring by a healthcare provider is essential to adjust the dosage as needed and to check for any adverse effects.

What is Niacin Side Effects

While niacin is generally safe when taken as prescribed, it can cause a range of side effects. The most common is flushing, which involves redness, warmth, itching, or tingling of the skin, usually on the face and neck. This side effect is more common with immediate-release formulations and can often be mitigated by taking aspirin 30 minutes before the niacin dose or by using extended-release formulations. Other common side effects include gastrointestinal issues such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.

More serious but less common side effects include liver toxicity, which can manifest as elevated liver enzymes in blood tests, jaundice, or other signs of liver dysfunction. Regular liver function tests are recommended for patients on long-term niacin therapy. High doses of niacin can also increase blood sugar levels, which is particularly concerning for diabetic patients. Therefore, blood glucose levels should be closely monitored.

Contraindications for niacin use include known hypersensitivity to niacin or any of its components, active liver disease, peptic ulcer disease, and arterial bleeding. Pregnant and breastfeeding women should consult their healthcare provider before starting niacin, as high doses may not be safe during pregnancy and lactation. Patients with a history of gout or gallbladder disease should use niacin with caution, as it can exacerbate these conditions.

What Other Drugs Will Affect Niacin

Several medications can interact with niacin, potentially altering its efficacy or increasing the risk of side effects. Statins, commonly prescribed alongside niacin for dyslipidemia, can increase the risk of myopathy or rhabdomyolysis, a severe form of muscle damage. Therefore, patients taking both niacin and statins should be closely monitored for muscle pain or weakness.

Blood pressure medications, particularly vasodilators and alpha-blockers, can enhance the blood pressure-lowering effects of niacin, potentially leading to hypotension. It's essential to monitor blood pressure regularly and adjust dosages as necessary under medical supervision.

Anticoagulants and antiplatelet drugs, such as warfarin and aspirin, can also interact with niacin, increasing the risk of bleeding. Patients on these medications should be monitored for signs of unusual bleeding or bruising, and regular blood tests may be required to ensure safe use.

Medications for diabetes can be affected by niacin's potential to raise blood sugar levels. Insulin and oral hypoglycemic agents may require dosage adjustments to maintain optimal blood glucose control. Additionally, bile acid sequestrants, used to lower cholesterol, can interfere with niacin absorption if taken simultaneously. To avoid this, niacin should be taken either one hour before or four to six hours after bile acid sequestrants.

In conclusion, niacin is a versatile and essential nutrient with significant therapeutic potential, particularly in managing lipid disorders and preventing cardiovascular diseases. Understanding its mechanisms, proper usage, potential side effects, and drug interactions is crucial for maximizing its benefits while minimizing risks. Regular consultations with healthcare providers are essential to ensure safe and effective use of niacin, tailored to individual health needs and conditions.

How to obtain the latest development progress of all drugs?

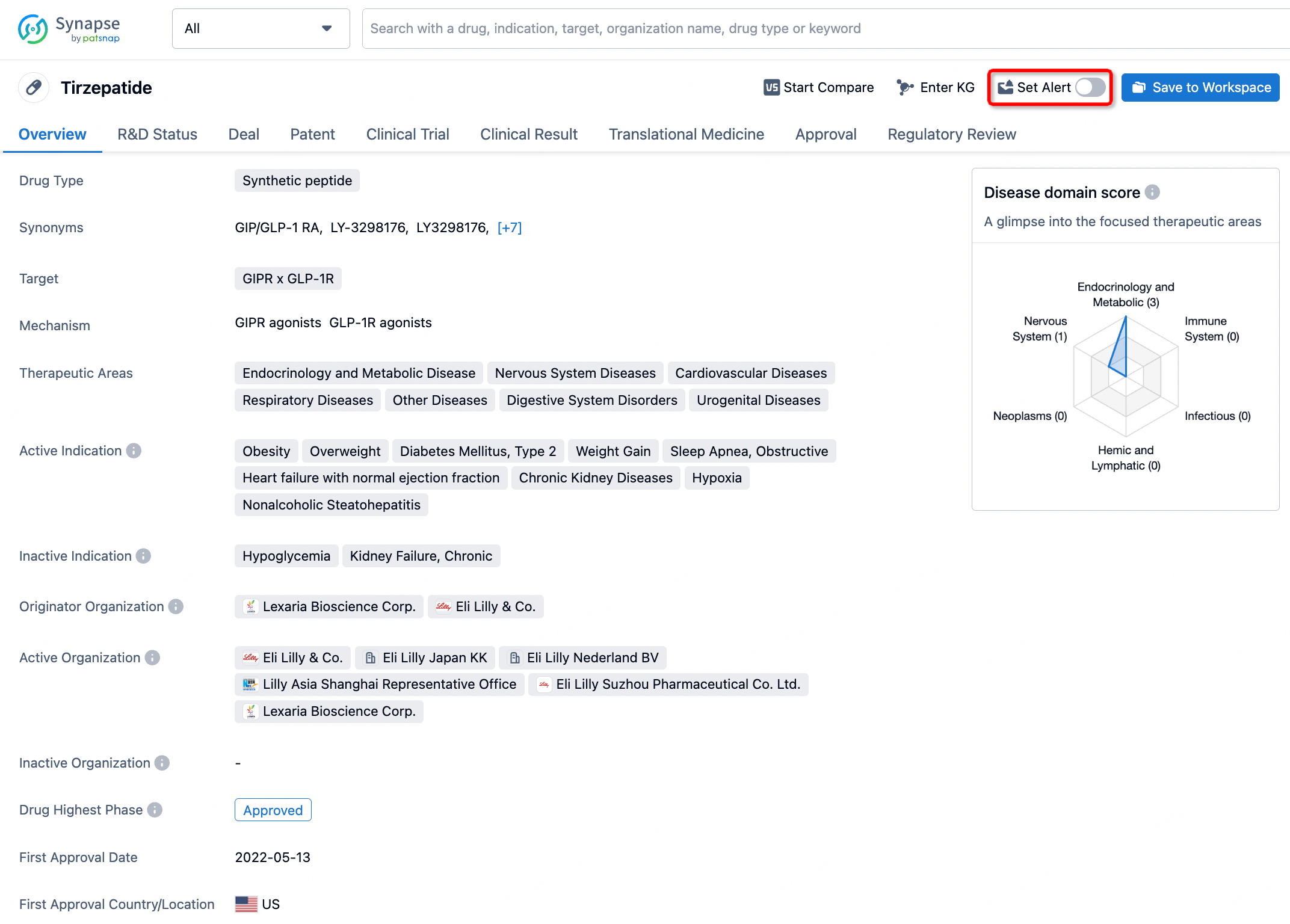

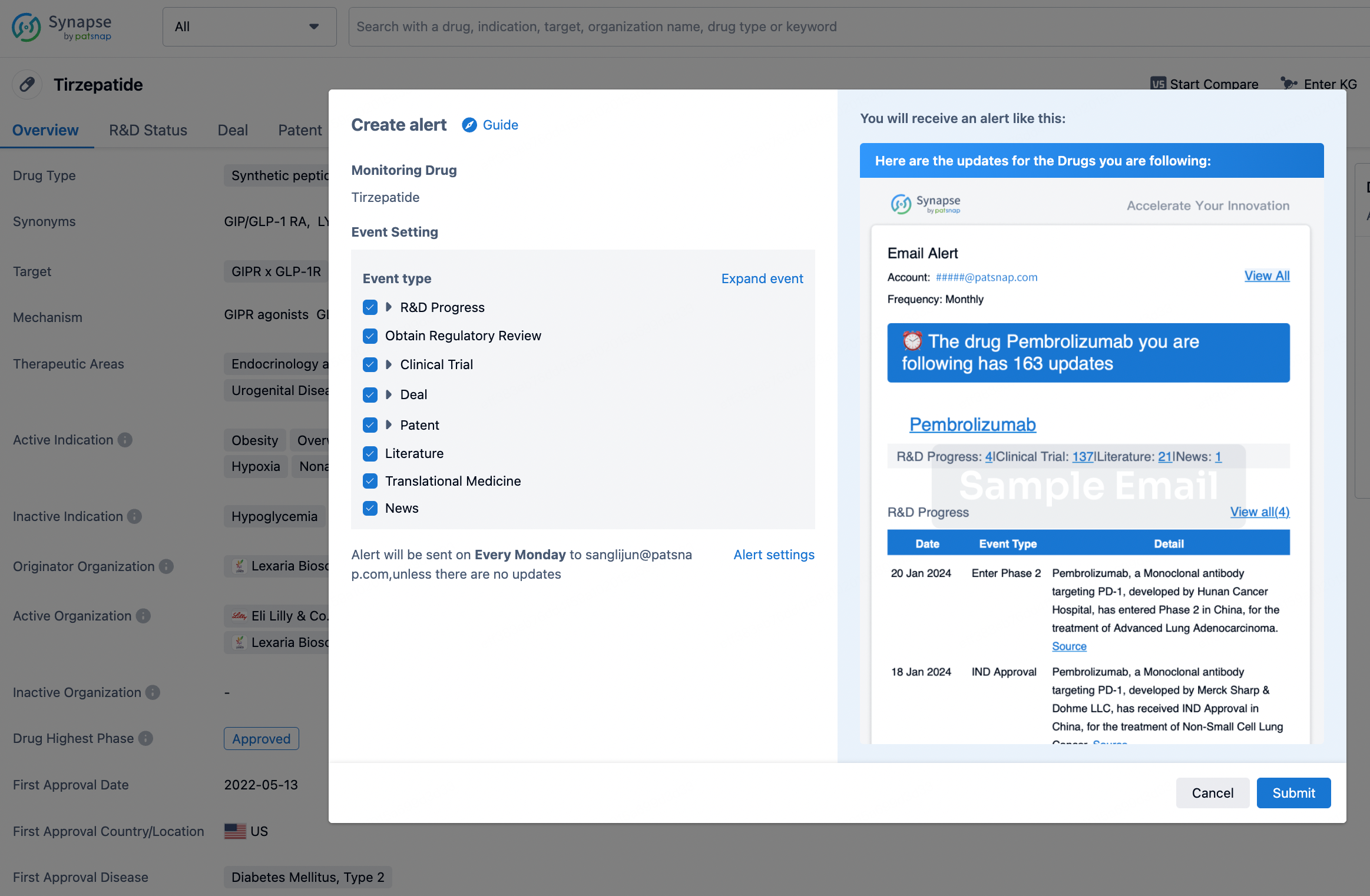

In the Synapse database, you can stay updated on the latest research and development advances of all drugs. This service is accessible anytime and anywhere, with updates available daily or weekly. Use the "Set Alert" function to stay informed. Click on the image below to embark on a brand new journey of drug discovery!

AI Agents Built for Biopharma Breakthroughs

Accelerate discovery. Empower decisions. Transform outcomes.

Get started for free today!

Accelerate Strategic R&D decision making with Synapse, PatSnap’s AI-powered Connected Innovation Intelligence Platform Built for Life Sciences Professionals.

Start your data trial now!

Synapse data is also accessible to external entities via APIs or data packages. Empower better decisions with the latest in pharmaceutical intelligence.