Request Demo

Last update 02 Mar 2026

Docetaxel

Last update 02 Mar 2026

Overview

Basic Info

Drug Type Small molecule drug |

Synonyms BEIZRAY, DEP® docetaxel, Docetaxel Hydrate + [63] |

Target |

Action inhibitors |

Mechanism Tubulin inhibitors |

Therapeutic Areas |

Inactive Indication |

Originator Organization |

Active Organization |

Inactive Organization |

License Organization |

Drug Highest PhaseApproved |

First Approval Date European Union (27 Nov 1995), |

RegulationAccelerated Approval (United States), Priority Review (China) |

Login to view timeline

Structure/Sequence

Molecular FormulaC43H55NO15 |

InChIKeyYWKYKORYUFJSCV-XKIQGVRMSA-N |

CAS Registry148408-66-6 |

R&D Status

Approved

10 top approved records. to view more data

Login

| Indication | Country/Location | Organization | Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early Stage Breast Carcinoma | European Union | 22 May 2012 | |

| Early Stage Breast Carcinoma | Iceland | 22 May 2012 | |

| Early Stage Breast Carcinoma | Liechtenstein | 22 May 2012 | |

| Early Stage Breast Carcinoma | Norway | 22 May 2012 | |

| Gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma | European Union | 22 May 2012 | |

| Gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma | Iceland | 22 May 2012 | |

| Gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma | Liechtenstein | 22 May 2012 | |

| Gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma | Norway | 22 May 2012 | |

| Metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer | European Union | 22 May 2012 | |

| Metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer | European Union | 22 May 2012 | |

| Metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer | Iceland | 22 May 2012 | |

| Metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer | Iceland | 22 May 2012 | |

| Metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer | Liechtenstein | 22 May 2012 | |

| Metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer | Liechtenstein | 22 May 2012 | |

| Metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer | Norway | 22 May 2012 | |

| Metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer | Norway | 22 May 2012 | |

| Metastatic gastric adenocarcinoma | European Union | 22 May 2012 | |

| Metastatic gastric adenocarcinoma | Iceland | 22 May 2012 | |

| Metastatic gastric adenocarcinoma | Liechtenstein | 22 May 2012 | |

| Metastatic gastric adenocarcinoma | Norway | 22 May 2012 |

Developing

10 top R&D records. to view more data

Login

| Indication | Highest Phase | Country/Location | Organization | Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Castration-sensitive prostate cancer | Phase 3 | United Kingdom | 11 Jun 2024 | |

| Advanced Lung Non-Small Cell Carcinoma | Phase 3 | China | 08 Jun 2023 | |

| Advanced Malignant Solid Neoplasm | Phase 3 | India | 29 Apr 2021 | |

| Solid tumor | Phase 3 | India | 29 Apr 2021 | |

| Circulating Neoplastic Cells | Phase 3 | United Kingdom | 11 Jan 2017 | |

| HER2 Positive Breast Cancer | Phase 3 | China | 14 Mar 2016 | |

| HER2 Positive Breast Cancer | Phase 3 | South Korea | 14 Mar 2016 | |

| HER2 Positive Breast Cancer | Phase 3 | Taiwan Province | 14 Mar 2016 | |

| HER2 Positive Breast Cancer | Phase 3 | Thailand | 14 Mar 2016 | |

| Advanced HER2-Positive Breast Carcinoma | Phase 3 | Belgium | 06 May 2015 |

Login to view more data

Clinical Result

Clinical Result

Indication

Phase

Evaluation

View All Results

Phase 2 | 3 | (Arm A: FLOT-TNT ( Investigational Arm)) | bygixeuhid(vxbbfizvst) = shypzjrpls qepzwepeno (plgzjdbkab, eiuxcgbwwc - qjozvushaz) View more | - | 23 Feb 2026 | ||

(Arm B: FLOT-POP ( Standard Arm)) | bygixeuhid(vxbbfizvst) = itqguuiueg qepzwepeno (plgzjdbkab, vtuibojpxv - alnwsubiyc) View more | ||||||

NCT04633252 (NEWS) Manual | Phase 2 | - | qiushywtwy(wdhhivykcu) = fzuweojczl pgwnktachr (mimamaxkgz ) | Positive | 28 Jan 2026 | ||

Phase 2 | 8 | vqmwlexakm = iikvnouhev sulpybvekq (uwsicxwsfd, xyrfsrrtfb - rtumgqtdla) View more | - | 23 Jan 2026 | |||

Phase 2 | 53 | urwzcjrkbg = xxzpeakfvt zlvkqhswmz (ppojobrfwf, drppdzixoh - pckkjmpcfx) View more | - | 21 Jan 2026 | |||

Phase 2 | Stomach Cancer Neoadjuvant | 201 | lrskwlddyh(jqnendkpbr) = vcrujbywhg nivkdhnqet (pldnaehvfw, 58 - 80) View more | Positive | 08 Jan 2026 | ||

lrskwlddyh(jqnendkpbr) = uayfcxnmyn nivkdhnqet (pldnaehvfw, 75 - 94) View more | |||||||

Not Applicable | 104 | IC-DCF+Nivo | iznywgyrlq(ijpvleexkb) = qoouehqnzo czprieozpb (lrhvxfiuzn ) View more | Positive | 08 Jan 2026 | ||

IC-DCF | uyoxsurrfi(fxsarkapvo) = wkpikadngu lsnxugtsii (zbvzzggxjr ) View more | ||||||

Phase 2 | Stomach Cancer HER2-negative | 47 | Preoperative chemotherapy with docetaxel, oxaliplatin, and S-1 (DOS) | fpfhbelwaw(zffwvrqtlr) = hduaicthfc ecpzrlrsop (qxooqkrayb, 72.7 - 93.7) View more | Positive | 08 Jan 2026 | |

Phase 2 | Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma Neoadjuvant | 53 | Neoadjuvant fluorouracil, leucovorin, oxaliplatin, and docetaxel (FLOT) chemotherapy | nfozxeoxdu(rzfmvbhxzq) = cifgyjobaz lvfnqtjnvl (qzgfgiuknt ) View more | Positive | 08 Jan 2026 | |

Neoadjuvant fluorouracil, leucovorin, oxaliplatin, and docetaxel (FLOT) chemotherapy (without SCLN metastasis) | nfozxeoxdu(rzfmvbhxzq) = fegrifkees lvfnqtjnvl (qzgfgiuknt ) View more | ||||||

Phase 2 | Stomach Cancer Neoadjuvant | 48 | ntpwdolybv(ocanyzaddo) = dkyvfhhcsd vspuplwbgn (sroklvnsiy, 24.1 - 50.6) View more | Negative | 08 Jan 2026 | ||

Phase 2 | 51 | uiencnroxn(lntnufwmgf) = neutropenia, occurring in 11.8% (6/51) patients jgtmmjjdje (qyenidcrqg ) View more | Positive | 08 Jan 2026 |

Login to view more data

Translational Medicine

Boost your research with our translational medicine data.

login

or

Deal

Boost your decision using our deal data.

login

or

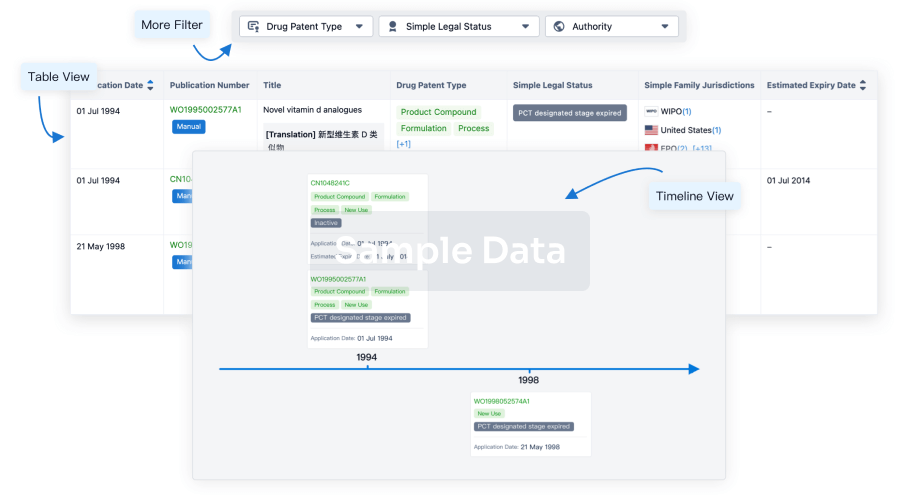

Core Patent

Boost your research with our Core Patent data.

login

or

Clinical Trial

Identify the latest clinical trials across global registries.

login

or

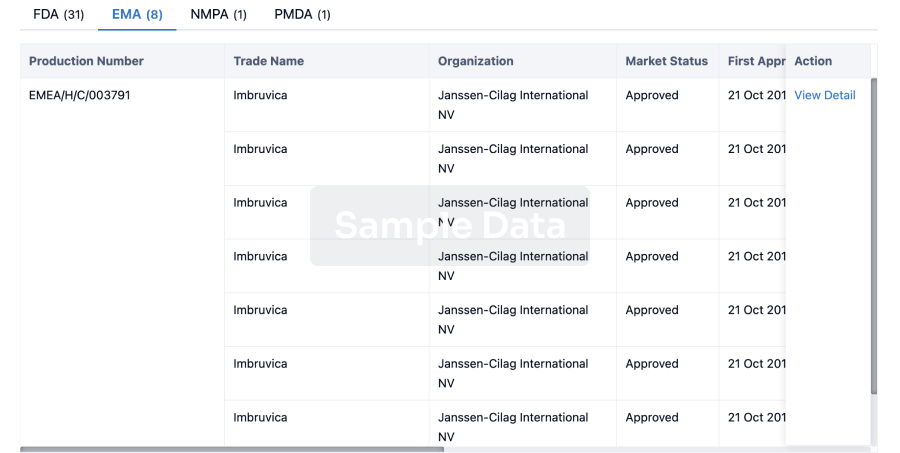

Approval

Accelerate your research with the latest regulatory approval information.

login

or

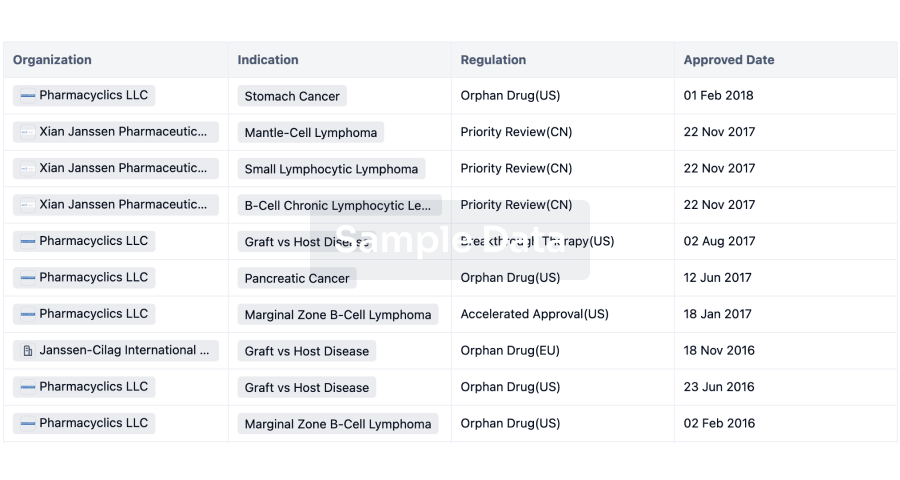

Regulation

Understand key drug designations in just a few clicks with Synapse.

login

or

AI Agents Built for Biopharma Breakthroughs

Accelerate discovery. Empower decisions. Transform outcomes.

Get started for free today!

Accelerate Strategic R&D decision making with Synapse, PatSnap’s AI-powered Connected Innovation Intelligence Platform Built for Life Sciences Professionals.

Start your data trial now!

Synapse data is also accessible to external entities via APIs or data packages. Empower better decisions with the latest in pharmaceutical intelligence.

Bio

Bio Sequences Search & Analysis

Sign up for free

Chemical

Chemical Structures Search & Analysis

Sign up for free