Request Demo

Last update 30 Oct 2025

Northwestern University

Last update 30 Oct 2025

Overview

Tags

Neoplasms

Other Diseases

Nervous System Diseases

Small molecule drug

Proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTAC)

Monoclonal antibody

Disease domain score

A glimpse into the focused therapeutic areas

No Data

Technology Platform

Most used technologies in drug development

No Data

Targets

Most frequently developed targets

No Data

| Top 5 Drug Type | Count |

|---|---|

| Small molecule drug | 37 |

| Proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTAC) | 10 |

| Monoclonal antibody | 6 |

| Chemical drugs | 3 |

| ASO | 2 |

Related

73

Drugs associated with Northwestern UniversityTarget |

Mechanism EZH2 inhibitors [+1] |

Active Org. |

Originator Org. |

Active Indication |

Inactive Indication |

Drug Highest PhaseApproved |

First Approval Ctry. / Loc. United States |

First Approval Date23 Jan 2020 |

Target |

Mechanism CDK4 inhibitors [+1] |

Active Org. |

Originator Org. |

Active Indication |

Inactive Indication |

Drug Highest PhaseApproved |

First Approval Ctry. / Loc. United States |

First Approval Date03 Feb 2015 |

Target |

Mechanism PD-1 inhibitors |

Active Org. |

Originator Org. |

Active Indication |

Inactive Indication |

Drug Highest PhaseApproved |

First Approval Ctry. / Loc. Japan |

First Approval Date04 Jul 2014 |

1,803

Clinical Trials associated with Northwestern UniversityNCT07127731

REACH BP: REmote Physical ACtivity Intervention for High Blood Pressure Postpartum

The purpose of this intervention is to help new mothers who had elevated blood pressure during pregnancy become more physically active after birth. The investigators will connect data from FitBits to the electronic health record. Women will then get weekly messages with feedback and goals to help them stay active. The investigators will test if the intervention improves step counts and blood pressure after pregnancy. The investigators will also test if the intervention is feasible and enjoyed by postpartum women.

Start Date01 Apr 2027 |

Sponsor / Collaborator |

NCT06545695

Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Inhibition for Keratinopathies

Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signaling plays a key role in regulating epidermal cell proliferation, survival, and differentiation. Keratins form a scaffold with epidermal desmosomes that involves ErbB/ EGFR signaling and keratin deficiency makes keratinocytes more sensitive to EGFR activation. Erlotinib, an EGFR inhibitor, was approved 20 years ago for cancer treatment and is generally used at 150 mg daily in adults >50 kg. While gastrointestinal and cutaneous side effects commonly occur at doses of 150 mg, adverse events occur less often at lower doses. We first reported erlotinib as effective for Olmsted syndrome, a rare hereditary EDD with painful PPK that results from variants in TRPV3. Erlotinib is now the treatment of choice for children and adults with Olmsted syndrome. Erlotinib is thought to inhibit formation of a complex that includes TRPV3, EGFR, and its primary skin-based ligand, TGF-a, which in turn regulates keratinocyte proliferation and differentiation. High-throughput screening to identify compounds that stabilize keratin filaments have also pointed to the EGFR pathway for targeting. Reviews and recent case reports have suggested the benefit of erlotinib for PC,

Given these preliminary data, we hypothesize that EGFR activation is a characteristic feature of keratinopathies. Further, we expect that oral low-dose erlotinib will improve the scaling and skin thickening of the spectrum of keratinopathies and be tolerated by most patients. For those who experience pain, particularly from plantar involvement, we predict that erlotinib therapy will improve mobility and pain. Finally, we aim to find the mechanism by which erlotinib improves the phenotypes of the various keratinopathies to better understand these disorders and predict response. We will look specifically at the impact on differentiation vs. hyperproliferation and barrier function, as well as the immune modulatory effects of the erlotinib using a multi-omics approach.

Given these preliminary data, we hypothesize that EGFR activation is a characteristic feature of keratinopathies. Further, we expect that oral low-dose erlotinib will improve the scaling and skin thickening of the spectrum of keratinopathies and be tolerated by most patients. For those who experience pain, particularly from plantar involvement, we predict that erlotinib therapy will improve mobility and pain. Finally, we aim to find the mechanism by which erlotinib improves the phenotypes of the various keratinopathies to better understand these disorders and predict response. We will look specifically at the impact on differentiation vs. hyperproliferation and barrier function, as well as the immune modulatory effects of the erlotinib using a multi-omics approach.

Start Date01 Dec 2026 |

Sponsor / Collaborator |

NCT04748146

CAUSAL MECHANISMS OF DISTRIBUTED BRAIN NETWORK FUNCTION DURING EPISODIC MEMORY RETRIEVAL

Brain stimulation is a means to potentially remediate symptoms in a range of neurological and psychiatric diseases, however, precise targeting of stimulation is necessary to ensure efficacy. The proposed project will use recent advances in functional magnetic resonance imaging to delineate distributed brain networks within individuals, and use these network maps to guide selection of intracranial electrodes for stimulation during an episodic memory task. The resulting data will refine the current understanding of the neural systems involved in episodic memory, and provide a proof-of-principle for the use of individual-level network mapping to guide brain stimulation, which could have important implications for brain stimulation therapies for a range of mental health disorders.

Start Date01 Aug 2026 |

Sponsor / Collaborator |

100 Clinical Results associated with Northwestern University

Login to view more data

0 Patents (Medical) associated with Northwestern University

Login to view more data

92,206

Literatures (Medical) associated with Northwestern University01 Dec 2025·JOURNAL OF CRITICAL CARE

Major publications in the critical care pharmacotherapy literature: 2024

Review

Author: Brown, Sophia ; Li, Ji ; Murray, Brian ; Farrar, Julie ; Roginski, Matthew A ; Bernardoni, Brittney ; Filiberto, Dina M ; Thompson, Tori R ; Perrodin, Jenna S ; Kopp, Brian J ; Esteves, Alyson M ; Madorsky, Melanie ; Tallon, Joanna K ; Moore, Megan J

OBJECTIVES:

To summarize, analyze, and provide clinical insights on the most impactful publications related to critical care pharmacotherapy in 2024.

METHODS:

A systematic search of PubMed/Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online (MEDLINE) was conducted between January 1, 2024, and December 31, 2024. Randomized controlled trials, prospective study designs, or retrospective study designs with high-quality methodology of adult critically ill patients assessing a pharmacotherapeutic intervention and reporting clinical endpoints were considered for inclusion. An a priori defined three-round modified Delphi process was performed to achieve consensus from a multi-disciplinary and geographically diverse group of critical care clinicians, focusing on the publications deemed most impactful based on their overall contribution to scientific knowledge and novelty.

RESULTS:

The systematic search yielded a total of 1533 articles, of which 1492 were excluded. Forty-one articles were included in the modified Delphi process. In each round, articles were independently scored based on their overall contribution to scientific knowledge and novelty and articles achieving a score at or above the median proceeded to the next round of voting. The six included articles are summarized and their impact is discussed. Article topics included cessation of proton pump inhibitors during transitions of care, stress ulcer prophylaxis in mechanically ventilated patients, continuous infusion beta-lactams in sepsis, ceftriaxone for prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia, optimal antibiotic duration for bloodstream infections, and andexanet alfa for management of intracranial hemorrhage associated with factor Xa inhibitors.

CONCLUSIONS:

This review identified, summarized, and evaluated high impact studies relevant to critical care pharmacotherapy published in 2024.

01 Dec 2025·INFLAMMATION RESEARCH

Silicone breast implant-associated pathologies and T cell-mediated responses

Review

Author: Shah, Shivani ; Jagasia, Puja ; Bagdady, Kazimir ; Taritsa, Iulianna ; Fracol, Megan

Silicone breast implants elicit a foreign body response (FBR) defined by a complex cascade of various immune cells. Studies have shown that the capsule around silicone breast implants that forms as a result of the FBR contains large T cell populations. T cells are implicated in pathologies such as capsular contracture, which is defined by an excessively fibrotic capsule, and breast implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma (BIA-ALCL), a non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. In this article, we provide a synthesis of 17 studies reporting on T cell-mediated responses to silicone breast implants and highlight recent developments on this topic. The lymphocytes present in the breast implant capsule are predominantly Th1 and Th17 cells. Patients with advanced capsular contracture had fewer T-regulatory (Treg) cells present in the capsules that were less able to suppress T effector cells such as Th17 cells, which can promote fibrosis in autoimmune conditions. Textured silicone implants, which are associated with BIA-ALCL, created a more robust T cell response, especially CD30 + T cells in the peri-implant fluid and CD4 + T cells in the capsule. Cultivating a deeper understanding of T cell-mediated responses to silicone breast implants may allow for novel treatments of breast implant-associated complications and malignancies.

01 Dec 2025·Current Diabetes Reports

Developing a Protocol for Management of Euglycemic Diabetic Ketoacidosis

Review

Author: Ritter, Kyle ; Aleppo, Grazia ; Kamal, Nevin ; Friedman, Jared G ; Szmuilowicz, Emily D ; Oakes, Diana J ; Makowski, Courtney T ; Cardona, Zulma ; Wallia, Amisha ; Brown, Sophia

Abstract:

Purpose of Review:

Euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis (euDKA) has been described since the 1970s, however the incidence appears to be increasing in association with the increased use of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor (SGLT2i) medications. Traditional hospital-based DKA protocols in which an insulin infusion is adjusted based on glucose levels are not effective in euDKA due to the presence of euglycemia which limits the capacity for insulin administration. This review was completed to review the data on euDKA and introduce a protocol for targeted management of this condition.

Recent Findings:

Data comparing euDKA outcomes to traditional hyperglycemia DKA demonstrate longer hospital length of stay and mean time to anion gap closure in euDKA based on current DKA management standards. Furthermore, the increase in prescribing SGLT2i medications thereby increases the risk of euDKA. At present, there are no reported protocols specific for euDKA and it is not directly addressed in the most recent guidelines issued by Endocrinology specialty societies.

Summary:

We created a protocol within our hospital intensive care unit to standardize treatment of euDKA using fixed insulin infusion and titration of dextrose-containing fluids. The protocol has been approved by our hospital regulatory committees and is currently being utilized in intensive care units. Future studies should review ongoing safety and efficacy of protocol use in various hospital settings.

827

News (Medical) associated with Northwestern University24 Oct 2025

New long-term extension data show approximately 80% of patients achieved or maintained meaningful skin improvement (EASI 75) with EBGLYSS with half the doses compared to approved monthly maintenance dosing

Lilly submitted these data to the FDA for a potential label update for EBGLYSS

If approved, EBGLYSS would be a first-line biologic that offers the option of monotherapy with once every eight-week maintenance dosing in moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis uncontrolled by topicals

INDIANAPOLIS, Oct. 24, 2025 /PRNewswire/ -- New results show Eli Lilly and Company's (NYSE: LLY) EBGLYSS (lebrikizumab-lbkz) sustained similar levels of skin clearance when administered as a single injection of 250 mg once every eight weeks (Q8W) compared with once every four weeks (Q4W), supporting a potential additional, less frequent maintenance dosing option for more individualized treatment of patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. These findings from the Phase 3 ADjoin extension trial will be presented at the 2025 Fall Clinical Dermatology Conference, taking place Oct. 23-26 in Las Vegas.1

"For people managing the persistent symptoms of eczema, hesitancy about frequent injections can add to the already heavy toll of this disease," said Peter Lio, M.D., author of the ADjoin study and clinical assistant professor of dermatology and pediatrics, Northwestern University. "With as few as six maintenance doses per year, EBGLYSS would give patients and providers more flexibility, which may reduce treatment burden for patients with busy lives."

EBGLYSS is an interleukin-13 (IL-13) inhibitor that selectively blocks IL-13 signaling with high binding affinity.2,3,4 The cytokine IL-13 is a primary cytokine in atopic dermatitis, driving the type-2 inflammatory cycle in the skin, leading to skin barrier dysfunction, itch, skin thickening and infection.5,6

In the ADjoin extension study, results indicate that maintenance dosing every other month demonstrated similarly high rates of disease control compared to monthly dosing:

79% of patients taking EBGLYSS once every other month and 86% of patients taking EBGLYSS monthly, respectively, achieved or maintained EASI 75.*

62% of patients taking EBGLYSS once every other month and 73% of patients taking EBGLYSS monthly, respectively, achieved or maintained IGA 0,1.

There was no increased risk of immunogenicity (the production of anti-drug-antibodies), and no new safety findings. These data support that once every eight-week EBGLYSS dosing could give HCPs and patients a new treatment option using the lowest effective dose.

"Managing moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis involves ongoing cycles of flare-ups and itching, which can be difficult for people with eczema," said Kristin Belleson, President and CEO of the National Eczema Association. "Treatment options that have the potential to reduce the time people spend managing symptoms could give them more time to focus on what matters most."

Lilly has submitted these data from the ADjoin extension trial among other data to the FDA for a potential label update. A study investigating EBGLYSS maintenance dosing of 500 mg administered once every 12 weeks (Q12W) is underway.

"Lilly continues to optimize dosing frequency to push boundaries that redefine the patient experience. These new findings build on EBGLYSS' proven efficacy and demonstrate the potential for disease control with even less frequent dosing," said Mark Genovese M.D., senior vice president of Lilly Immunology development. "We are pursuing an every-eight-week maintenance dosing label update with the FDA. We are also testing every-twelve-week maintenance dosing with our partner Almirall, as well as potentially exploring every-twelve-week dosing in independent Lilly-led studies."

These data build on existing research for EBGLYSS, which has demonstrated long-term results maintained for up to three years, as well as efficacy data across diverse skin tones. EBGLYSS is the only biologic for moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis with a strong recommendation and high certainty of evidence that can be used with or without topicals, according to guidelines published by the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD),** which are used as a key consideration for dermatologists and managed care providers.

Lilly continues to raise the standard of care in dermatology and invest in our immunology pipeline, which includes big bets on next-generation modalities and the targeted expansion of small molecules. Lilly's investigational therapies include novel, oral IL-17 inhibitors such as DICE Therapeutics' DC-853, which is being studied for psoriasis, and eltrekibart, a novel monoclonal antibody that targets neutrophil-driven inflammation and is being assessed in hidradenitis suppurativa. Lilly is also advancing novel science to explore the potential of incretins in dermatology and has initiated the TOGETHER-PsO trial investigating the efficacy and safety of treating adults with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis and obesity with both ixekizumab and an incretin-based therapy.

Lilly has exclusive rights for development and commercialization of EBGLYSS in the U.S. and the rest of the world outside Europe. Lilly's partner Almirall has licensed the rights to develop and commercialize EBGLYSS for the treatment of dermatology indications, including atopic dermatitis, in Europe.

*EASI=Eczema Area and Severity Index, EASI-75=75% reduction in EASI from baseline; IGA=Investigator's Global Assessment 0 or 1 ("clear" or "almost clear").

**Inclusion in the Focused Update: AAD Guidelines of Care for the Management of Atopic Dermatitis in Adults does not denote endorsement of product use by the AAD.

About the Q8W ADjoin Extension

The Q8W extension of ADjoin (NCT04392154) assessed EBGLYSS given every eight weeks (Q8W) compared to every four weeks (Q4W) and evaluated the long-term safety and efficacy of EBGLYSS treatment in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis for 32 weeks, in select countries. Adult and adolescent patients (ages 12–17, weighing ≥40 kg) who completed the 100-week ADjoin study, including participants from the ADvocate 1 and 2 trials (52 weeks), ADore trial (52 weeks) and the ADopt-VA (16 weeks) trial, were eligible to enroll in the Q8W extension. Patients in this analysis received open-label EBGLYSS 250 mg, Q8W or Q4W, regardless of their previous treatment in ADjoin (Q2W or Q4W dose). The approved maintenance dose of EBGLYSS is 250 mg once monthly, after taking EBGLYSS 250 mg every two weeks for 16 weeks or later when adequate clinical response is achieved.7

INDICATION AND SAFETY SUMMARY

EBGLYSS™ (EHB-glihs) is an injectable medicine used to treat adults and children 12 years of age and older who weigh at least 88 pounds (40 kg) with moderate-to-severe eczema (atopic dermatitis) that is not well controlled with prescription therapies used on the skin (topical), or who cannot use topical therapies. EBGLYSS can be used with or without topical corticosteroids.

It is not known if EBGLYSS is safe and effective in children less than 12 years of age or in children 12 years to less than 18 years of age who weigh less than 88 pounds (40 kg).

Warnings - Do not use

EBGLYSS if you are allergic to lebrikizumab-lbkz or to any of the ingredients in EBGLYSS. See the Patient Information leaflet that comes with EBGLYSS for a complete list of ingredients.

Before using

Before using EBGLYSS, tell your healthcare provider about all your medical conditions, including if you:

Have a parasitic (helminth) infection.

Are scheduled to receive any vaccinations. You should not receive a "live vaccine" if you are treated with EBGLYSS.

Are pregnant or plan to become pregnant. It is not known if EBGLYSS will harm your unborn baby. If you become pregnant during treatment with EBGLYSS, you or your healthcare provider can call Eli Lilly and Company at 1-800-LillyRx (1-800-545-5979) to report the pregnancy.

Are breastfeeding or plan to breastfeed. It is not known if EBGLYSS passes into your breast milk.

Tell your healthcare provider about all the medicines you take, including prescription and over-the-counter medicines, vitamins, and herbal supplements.

Possible side effects

EBGLYSS can cause serious side effects, including:

Allergic reactions. EBGLYSS can cause allergic reactions that may sometimes be severe. Stop using EBGLYSS and tell your healthcare provider or get emergency help right away if you get any of the following signs or symptoms:

breathing problems or wheezing

swelling of the face, lips, mouth, tongue or throat

hives

itching

fainting, dizziness, feeling lightheaded

skin rash

cramps in your stomach area (abdomen)

Eye problems. Tell your healthcare provider if you have any new or worsening eye problems, including eye pain or changes in vision, such as blurred vision.

The most common side effects of EBGLYSS include:

eye and eyelid inflammation, including redness, swelling, and itching

injection site reactions

shingles (herpes zoster)

These are not all of the possible side effects of EBGLYSS. Call your doctor for medical advice about side effects. You may report side effects to FDA at 1-800-FDA-1088 or .

How to take

See the detailed "Instructions for Use" that comes with EBGLYSS for information about how to prepare and inject EBGLYSS and how to properly store and throw away (dispose of) used EBGLYSS prefilled pens and prefilled syringes.

Use EBGLYSS exactly as prescribed by your healthcare provider.

EBGLYSS is given as an injection under the skin (subcutaneous injection).

If your healthcare provider decides that you or a caregiver can give the injections of EBGLYSS, you or a caregiver should receive training on the right way to prepare and inject EBGLYSS. Do not try to inject EBGLYSS until you have been shown the right way by your healthcare provider. In children 12 years of age and older, EBGLYSS should be given by a caregiver.

If you miss a dose of EBGLYSS, inject the missed dose as soon as possible, then inject your next dose at your regular scheduled time.

Learn more

EBGLYSS is a prescription medicine available as a 250 mg/2 mL injection prefilled pen or prefilled syringe. For more information, call

1-800-545-5979 or go to

ebglyss.lilly.com

This summary provides basic information about EBGLYSS but does not include all information known about this medicine. Read the information that comes with your prescription each time your prescription is filled. This information does not take the place of talking to your doctor. Be sure to talk to your doctor or other healthcare provider about EBGLYSS and how to take it. Your doctor is the best person to help you decide if EBGLYSS is right for you.

LK CON BS AD APP

EBGLYSS, its delivery device base, and Lilly Support Services are trademarks owned or licensed by Eli Lilly and Company, its subsidiaries, or affiliates.

About EBGLYSS

EBGLYSS is a monoclonal antibody that selectively targets and neutralizes IL-13 with high binding affinity and a slow dissociation rate.3,4,7 EBGLYSS binds to the IL-13 cytokine at an area that overlaps with the binding site of the IL-4Rα subunit of the IL-13Rα1/IL-4Rα heterodimer, preventing formation of this receptor complex and inhibiting IL-13 signaling. IL-13 is implicated as a primary cytokine tied to the pathophysiology of eczema, driving the type-2 inflammatory loop in the skin, and EBGLYSS selectively targets IL-13.7

The EBGLYSS Phase 3 program consists of five key global studies evaluating over 1,300 patients, including two monotherapy studies (ADvocate 1 and 2), a combination study with topical corticosteroids (ADhere), as well as long-term extension (ADjoin) and adolescent open label (ADore) studies.

EBGLYSS was approved in the U.S. by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2024 as a first-line monotherapy biologic treatment with once-monthly maintenance dosing for adults and children 12 years of age and older who weigh at least 88 pounds (40 kg) with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis that is not well controlled with topical prescription therapies.7 EBGLYSS was also approved in the European Union in 2023 and in Japan and Canada in 2024.

EBGLYSS 250 mg/2 mL injection is dosed as a single monthly maintenance injection following the initial phase of treatment. The recommended initial starting dose of EBGLYSS is 500 mg (two 250 mg injections) at Week 0 and Week 2, followed by 250 mg every two weeks until Week 16 or later when adequate clinical response is achieved; after this, maintenance dosing is a single monthly injection (250 mg every four weeks).7

Lilly is committed to serving patients living with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis and is working to enable broad first-line biologic access to EBGLYSS following topical prescription therapy through commercial insurance and as of October 24, Lilly has coverage with all three major national pharmacy benefit managers and over 90% of people with commercial insurance. We are also pursuing similarly broad Medicaid and Medicare coverage as part of Lilly's health access and affordability initiative. Through Lilly Support Services, Lilly offers a patient support program including co-pay assistance for eligible, commercially insured patients.

About Lilly

Lilly is a medicine company turning science into healing to make life better for people around the world. We've been pioneering life-changing discoveries for nearly 150 years, and today our medicines help tens of millions of people across the globe. Harnessing the power of biotechnology, chemistry and genetic medicine, our scientists are urgently advancing new discoveries to solve some of the world's most significant health challenges: redefining diabetes care; treating obesity and curtailing its most devastating long-term effects; advancing the fight against Alzheimer's disease; providing solutions to some of the most debilitating immune system disorders; and transforming the most difficult-to-treat cancers into manageable diseases. With each step toward a healthier world, we're motivated by one thing: making life better for millions more people. That includes delivering innovative clinical trials that reflect the diversity of our world and working to ensure our medicines are accessible and affordable. To learn more, visit Lilly.com and Lilly.com/news, or follow us on Facebook, Instagram and LinkedIn. P-LLY

Trademarks and Trade Names

All trademarks or trade names referred to in this press release are the property of the company, or, to the extent trademarks or trade names belonging to other companies are references in this press release, the property of their respective owners. Solely for convenience, the trademarks and trade names in this press release are referred to without the ® and ™ symbols, but such references should not be construed as any indicator that the company or, to the extent applicable, their respective owners will not assert, to the fullest extent under applicable law, the company's or their rights thereto. We do not intend the use or display of other companies' trademarks and trade names to imply a relationship with, or endorsement or sponsorship of us by, any other companies.

Cautionary Statement Regarding Forward-Looking Statements

This press release contains forward-looking statements (as that term is defined in the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995) about EBGLYSS (lebrikizumab-lbkz) as a treatment for patients with moderate-to severe atopic dermatitis and the timeline for future readouts, presentations, and other milestones relating to EBGLYSS and its clinical trials and reflects Lilly's current beliefs and expectations. However, as with any pharmaceutical product, there are substantial risks and uncertainties in the process of drug research, development, and commercialization. Among other things, there is no guarantee that future study results will be consistent with the results to date or that EBGLYSS will receive additional regulatory approvals, or that it will be commercially successful. For further discussion of these and other risks and uncertainties that could cause actual results to differ from Lilly's expectations, see Lilly's Form 10-K and Form 10-Q filings with the United States Securities and Exchange Commission. Except as required by law, Lilly undertakes no duty to update forward-looking statements to reflect events after the date of this release.

Silverberg J, et al. Lebrikizumab Dosed Every 8 Weeks as Maintenance Provides Long-Lasting Response in Patients with Moderate-to-Severe Atopic Dermatitis. 2025 Fall Clinical Dermatology Conference. October 24, 2025.

Simpson EL, et al. Efficacy and safety of lebrikizumab (an anti-IL-13 monoclonal antibody) in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis inadequately controlled by topical corticosteroids: A randomized, placebo-controlled phase II trial (TREBLE). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78(5):863-871.e11. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.01.017.

Okragly A, et al. Binding, Neutralization and Internalization of the Interleukin-13 Antibody, Lebrikizumab. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2023;13(7):1535-1547. doi:10.1007/s13555-023-00947-7.

Ultsch M, et al. Structural basis of signaling blockade by anti-IL-13 antibody Lebrikizumab. J Mol Biol. 2013;425(8):1330-1339. doi:10.10116/j.jmb.2013.01.024.

Bieber T. Interleukin-13: Targeting an underestimated cytokine in atopic dermatitis. Allergy. 2020;75(1):54–62. doi:10.1111/all.13954.

Tsoi LC, et al. Atopic Dermatitis Is an IL-13-Dominant Disease with Greater Molecular Heterogeneity Compared to Psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2019;139(7):1480-1489. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2018.12.018.

EBGLYSS. Prescribing Information. Lilly USA, LLC.

SOURCE Eli Lilly and Company

WANT YOUR COMPANY'S NEWS FEATURED ON PRNEWSWIRE.COM?

440k+

Newsrooms &

Influencers

9k+

Digital Media

Outlets

270k+

Journalists

Opted In

GET STARTED

Clinical ResultPhase 3Drug ApprovalPhase 2License out/in

21 Oct 2025

CHARLOTTESVILLE, Va., Oct. 21, 2025 /PRNewswire/ -- RIVANNA®, developers of world-first imaging-based medical technologies, has been awarded with a Peer-Reviewed Medical Research Program (PRMRP) Technology/Therapeutic Development Award (TTDA) from the Congressionally Directed Medical Research Program (CDMRP). The award total from this grant is $3 million over a 36-month period.

Annually, nearly 150,000 personnel in the United States (US) armed forces experience back pain and/or spinal injuries. These conditions cause an estimated 6 million limited-duty days and cost around $2 billion annually. An effective treatment that can mitigate inflammation and pain are epidural steroid injections (ESI). While this treatment may allow members to return to active duty more quickly, this approach requires real-time imaging guidance for accurate needle placement. This need was traditionally met with x-ray fluoroscopy, but for forward-deployed military hospitals, this technology is impractical for a number of reasons, such as cost, size, and the need for specialized facilities. Because of these issues, personnel often experience treatment delays and costly evacuations from theatre to access advanced imaging capabilities and specialized medical providers. There is a clear unmet need for a more effective, efficient solution that can be utilized in far-forward scenarios.

In order to address this need, RIVANNA will collaborate with leading military healthcare experts to develop the Accuro® 3S-MIL. For this project, RIVANNA will partner with The Geneva Foundation, a leading non-profit organization, which facilitates the Musculoskeletal Injury Rehabilitation Research for Operational Readiness (MIRROR) program. MIRROR was established by the Defense Health Agency (DHA) to support the treatment and care of non-combat-related musculoskeletal injury. Together, this collaboration will work to transform the standard of care for back pain and spinal injury in military settings.

"Partnering with RIVANNA is a pivotal step for advancing innovative solutions in the Military Health System (MHS). With a combination of operational insight and cutting-edge technology, we are strengthening service members' and their families' future of care. Our collaboration with RIVANNA allows for the integration of emerging technologies into the MHS, which will enhance clinical decision support, operational readiness, and data interoperability. Our partnership is a vital step toward modernizing healthcare delivery across military environments," said Linzie Wagner, Senior Manager, MIRROR program, The Geneva Foundation.

This variant of Accuro 3S, a portable ultrasound guidance system, will be optimized for use in military settings by making the system more compact and durable within operational environments. Additional modifications will include integrating the device with military electronic health records systems and adaptation of AI-based imaging innovations for high performance with service member demographics. The 3S-MIL variant will undergo evaluations with military clinicians as well as validation studies to ensure its performance in military medical centers and hospitals.

RIVANNA also intends to file for FDA 510(k) clearance of the Accuro 3S-MIL as a commercial product. Through enabling the administration of ESI in military settings, 3S-MIL carries the potential to improve the military's capability of addressing back pain, reducing the need for evacuations and allowing service members to return to duty more quickly. Planned follow-on clinical studies will assess the device's impacts on cost-effectiveness and return to duty rates.

Furthermore, RIVANNA anticipates expanding the 3S-MIL's indications for support of a wider array of neuraxial anesthesia and pain management applications that could enhance treatment in civilian and military settings. This mobile, radiation-free, easy-to-use device has the potential to become a new standard of care, potentially helping to treat millions of people living with back pain globally.

This initiative is supported by a distinguished team of collaborators, including:

DoD Co-Principal Investigator: Dr. Xiaoning (Jenny) Yuan, Assistant Professor and Vice Chair for Research in Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences (USU); Director of the Musculoskeletal Injury Rehabilitative Research for Operational Readiness (MIRROR) Program; active clinician at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center (WRNMMC).

DoD Co-Investigator: Dr. Edward Dolomisiewicz, Associate Program Director of the Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Residency Program at WRNMMC in Bethesda, MD.

Subject Matter Expert: Dr. Steven P. Cohen, Edmond I Eger Professor of Anesthesiology, Vice Chair of Research at Northwestern University; Professor and Director of Pain Research, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center; President-elect of the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine (ASRA Pain Medicine); retired U.S. Army Colonel; recognized as a leading expert in pain management.

Subject Matter Expert: Dr. Amitabh Gulati, President of the World Academy of Pain Medicine United (WAPMU); Director of Chronic Pain at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City.

Sites: Walter Reed National Military Medical Center and the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences.

Acknowledgement

The U.S. Army Medical Research Acquisition Activity, 808 Schreider Street, Fort Detrick MD 21702-5014 is the awarding and administering acquisition office. This work was supported by The Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs endorsed by the Department of Defense, in the amount of $3 million through the Peer Reviewed Medical Research Program under Award Number HT94252510463. Opinions, interpretations, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the author(s) and are not necessarily endorsed by The Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs endorsed by the Department of Defense.

About RIVANNA

RIVANNA® is a commercial-stage medical device innovator and manufacturer in Charlottesville, VA. RIVANNA develops and commercializes world-first imaging-based medical technologies that elevate global standards of care. The company provides early- and late-stage comprehensive imaging solutions for point-of-care spinal needle interventions and musculoskeletal diagnostics.

Learn more: RIVANNA.

About The Geneva Foundation

Geneva advances operationally relevant, military-unique research aligned with DoD requirements to ensure mission success. We accelerate military medical R&D to deliver deployable solutions that enhance the health, readiness, and capabilities of service members and the communities they serve. With deep expertise in research operations, government contracting, strategic collaborations, and commercialization, Geneva ensures successful research outcomes and remains a committed strategic partner in advancing military medicine.

Learn more: The Geneva Foundation.

SOURCE RIVANNA

WANT YOUR COMPANY'S NEWS FEATURED ON PRNEWSWIRE.COM?

440k+

Newsrooms &

Influencers

9k+

Digital Media

Outlets

270k+

Journalists

Opted In

GET STARTED

Radiation Therapy

21 Oct 2025

79 clinical sites across 23 US states are currently enrolling patients in BriaCell’s pivotal Phase 3 study in metastatic breast cancer (MBC) Dartmouth Cancer Center, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, and Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University have now joined BriaCell’s extensive national network PHILADELPHIA and VANCOUVER, British Columbia, Oct. 21, 2025 (GLOBE NEWSWIRE) -- BriaCell Therapeutics Corp. (Nasdaq: BCTX, BCTXW) (TSX: BCT) (“BriaCell” or the “Company”), a clinical-stage biotechnology company that develops novel immunotherapies to transform cancer care, is pleased to announce the addition of several key large cancer centers to its ongoing pivotal Phase 3 clinical study (ClinicalTrials.gov as NCT06072612), notably Dartmouth Cancer Center, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, and Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University. BriaCell anticipates reporting top line data as early as H1-2026. The extensive national effort already includes the following noteworthy clinics: Mayo Clinic, Los Angeles Cancer Network, Smilow Cancer Hospital at Yale New Haven, Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center, Cancer Care Northwest, Hematology Oncology Associates of Fredericksburg, Northwestern University, Manhattan Hematology/Oncology Associates, New York Cancer and Bood Specialists, and Texas Oncology-Baylor Charles A. Sammons Cancer Center. BriaCell’s pivotal Phase 3 clinical study is evaluating BriaCell’s lead clinical candidate, Bria-IMT, plus immune check point inhibitor versus physician’s choice of treatment in advanced metastatic breast cancer (Bria-ABC). “We are encouraged by the strong engagement from major academic and leading community cancer centers which underscores confidence in BriaCell’s novel technology,” stated Dr. William V. Williams, BriaCell’s President & CEO. “We expect the addition of these clinical sites will further accelerate patient enrollment in BriaCell’s pivotal Phase 3 study of Bria-IMT regimen in MBC and support our mission to bring this therapy to patients with significant unmet medical needs.” About BriaCell’s Pivotal Phase 3 Clinical Study of Bria-IMT Combination Regimen in MBC patients BriaCell’s pivotal Phase 3 study of Bria-IMT plus an immune check point inhibitor (CPI) in metastatic breast cancer is ongoing. Interim data will be analyzed once 144 patient events (deaths) occur, comparing the overall survival (OS) in patients treated with the Bria-IMT combination regimen versus those treated with physician’s choice as the primary endpoint. Positive results of the pivotal Phase 3 study could result in full approval and marketing authorization for Bria-IMT in MBC patients. The Bria-IMT combination regimen has received FDA Fast Track designation. For additional information on BriaCell’s pivotal Phase 3 study of Bria-IMT and an immune check point inhibitor in metastatic breast cancer, please visit ClinicalTrials.gov NCT06072612. About BriaCell Therapeutics Corp. BriaCell is a clinical-stage biotechnology company that develops novel immunotherapies to transform cancer care. More information is available at https://briacell.com/. Safe Harbor This press release contains “forward-looking statements” that are subject to substantial risks and uncertainties. All statements, other than statements of historical fact, contained in this press release are forward-looking statements. Forward-looking statements contained in this press release may be identified by the use of words such as “anticipate,” “believe,” “contemplate,” “could,” “estimate,” “expect,” “intend,” “seek,” “may,” “might,” “plan,” “potential,” “predict,” “project,” “target,” “aim,” “should,” “will,” “would,” or the negative of these words or other similar expressions, although not all forward-looking statements contain these words. Forward-looking statements, including those about: the Company’s anticipated expansion of patient enrollment; the Company's anticipated timeline for analyzing and reporting interim and top line data in its ongoing pivotal Phase 3 clinical study; and the Company’s beliefs regarding its ability to bring their novel immunotherapy to patients with unmet medical needs; are based on BriaCell’s current expectations and are subject to inherent uncertainties, risks, and assumptions that are difficult to predict. Further, certain forward-looking statements, such as those are based on assumptions as to future events that may not prove to be accurate. These and other risks and uncertainties are described more fully under the heading “Risks and Uncertainties” in the Company’s most recent Management’s Discussion and Analysis, under the heading “Risk Factors” in the Company’s most recent Annual Information Form, and under “Risks and Uncertainties” in the Company’s other filings with the Canadian securities regulatory authorities and the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, all of which are available under the Company's profiles on SEDAR+ at www.sedarplus.ca and on EDGAR at www.sec.gov. Forward-looking statements contained in this announcement are made as of this date, and BriaCell Therapeutics Corp. undertakes no duty to update such information except as required under applicable law. Neither the Toronto Stock Exchange nor its Regulation Services Provider (as that term is defined in the policies of the Toronto Stock Exchange) accepts responsibility for the adequacy or accuracy of this release. Contact Information Company Contact:William V. Williams, MDPresident & CEO1-888-485-6340info@briacell.com Investor Relations Contact:investors@briacell.com

Phase 3ImmunotherapyFast Track

100 Deals associated with Northwestern University

Login to view more data

100 Translational Medicine associated with Northwestern University

Login to view more data

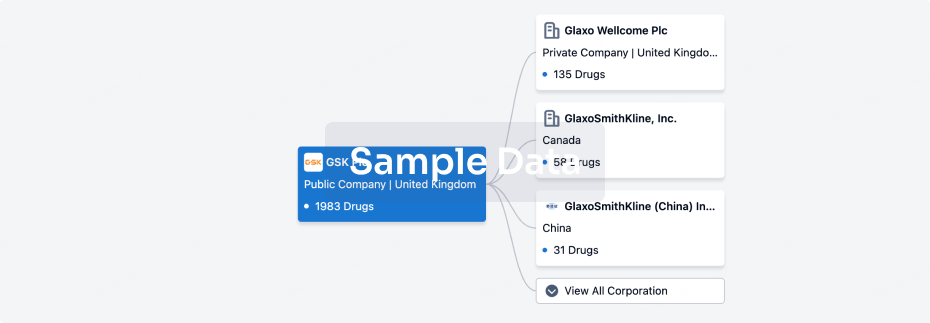

Corporation Tree

Boost your research with our corporation tree data.

login

or

Pipeline

Pipeline Snapshot as of 22 Feb 2026

The statistics for drugs in the Pipeline is the current organization and its subsidiaries are counted as organizations,Early Phase 1 is incorporated into Phase 1, Phase 1/2 is incorporated into phase 2, and phase 2/3 is incorporated into phase 3

Discovery

20

38

Preclinical

Phase 1

8

5

Phase 2

Phase 3

1

43

Other

Login to view more data

Current Projects

| Drug(Targets) | Indications | Global Highest Phase |

|---|---|---|

Cocoa flavanols | Peripheral arterial occlusive disease More | Phase 3 |

Fluorouracil ( TYMS ) | Advanced Malignant Solid Neoplasm More | Phase 2 |

Devimistat ( PDC complex ) | Advanced Malignant Solid Neoplasm More | Phase 2 |

Palbociclib ( CDK4 x CDK6 ) | Advanced breast cancer More | Phase 2 |

Vudalimab ( CTLA4 x PD-1 ) | Thyroid Cancer, Hurthle Cell More | Phase 2 |

Login to view more data

Deal

Boost your decision using our deal data.

login

or

Translational Medicine

Boost your research with our translational medicine data.

login

or

Profit

Explore the financial positions of over 360K organizations with Synapse.

login

or

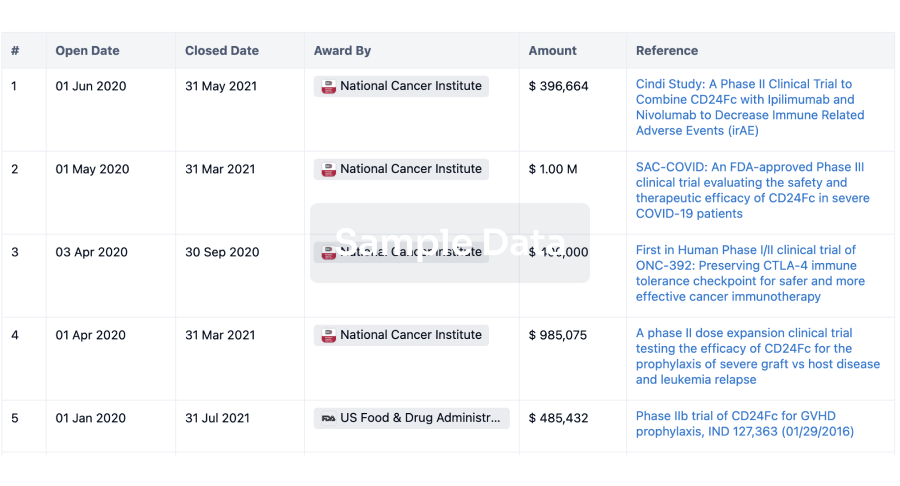

Grant & Funding(NIH)

Access more than 2 million grant and funding information to elevate your research journey.

login

or

Investment

Gain insights on the latest company investments from start-ups to established corporations.

login

or

Financing

Unearth financing trends to validate and advance investment opportunities.

login

or

AI Agents Built for Biopharma Breakthroughs

Accelerate discovery. Empower decisions. Transform outcomes.

Get started for free today!

Accelerate Strategic R&D decision making with Synapse, PatSnap’s AI-powered Connected Innovation Intelligence Platform Built for Life Sciences Professionals.

Start your data trial now!

Synapse data is also accessible to external entities via APIs or data packages. Empower better decisions with the latest in pharmaceutical intelligence.

Bio

Bio Sequences Search & Analysis

Sign up for free

Chemical

Chemical Structures Search & Analysis

Sign up for free